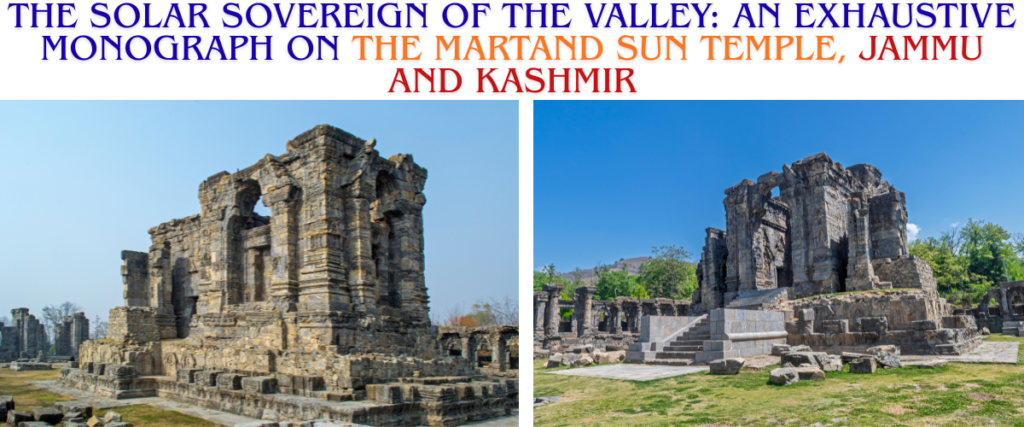

The Martand Sun Temple, perched atop the alluvial plateau of Mattan in the Anantnag district of Jammu and Kashmir, is not merely a ruin of limestone and memory; it is a monumental testament to a pivotal epoch in the history of the Indian subcontinent. Commissioned in the 8th century CE by Emperor Lalitaditya Muktapida of the Karkota Dynasty, this edifice was conceived as a grand architectural hymn to Surya, the Sun God, encapsulating the imperial ambitions, spiritual fervour, and artistic syncretism of its age.1 Today, its cyclopean walls and colonnaded courtyards stand roofless under the open sky, bearing the scars of medieval iconoclasm and the relentless erosion of time. Yet, even in this state of dilapidation, the temple commands a profound presence, overlooking the Kashmir Valley with a grandeur that continues to captivate historians, archaeologists, and pilgrims alike.

The significance of the Martand Sun Temple transcends its physical dimensions. It serves as a lithic document of the “Golden Age” of Kashmir, a period when the valley functioned as a vibrant crucible of civilisation where Indian, Gandharan, Chinese, and Hellenistic influences converged to create a unique cultural idiom.3 The temple’s architecture—a distinct “Kashmiri Style”—challenges conventional categorisations of Indian temple design, featuring triangular pediments reminiscent of Greek temples alongside the trefoil arches of Buddhist chaityas and the towering shikharas of the Hindu plains.4

However, the narrative of Martand is also one of rupture and loss. Its systematic destruction in the 15th century, attributed to Sultan Sikandar Shah Miri, marks a traumatic watershed in the region’s history, transforming a thriving centre of solar worship into a symbol of religious conflict and cultural displacement.6 In contemporary discourse, the ruins have re-emerged as a focal point of intense debate regarding heritage management, religious reclamation, and political identity. Designated as a “Site of National Importance” by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), the temple sits at the intersection of preservationist ethics and the living religious sentiments of the Kashmiri Pandit community, a tension exemplified by recent controversies over prayer gatherings and restoration initiatives.8

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the Martand Sun Temple. It traverses the geological and mythological origins of the site, the geopolitical might of its builder, the intricate details of its architectural anatomy, the historiography of its destruction, and the unfolding narrative of its conservation in the 21st century. Through a nuanced examination of historical records, archaeological findings, and current affairs, this document aims to construct a holistic understanding of a site that remains, despite its ruins, the “Sun of Kashmir”—a beacon of a glorious past that refuses to set completely.

The Geo-Mythological Landscape: Mattan and the Solar Cult

The Geological Pedestal: The Karewa of Mattan

The location chosen for the Martand Sun Temple was neither accidental nor purely pragmatic; it was a decision rooted in both strategic visibility and sacred geography. The temple is situated on a karewa—a tableland or plateau formed of alluvial deposits, characteristic of the Kashmir Valley’s geological history.11 Located approximately 64 kilometres from Srinagar and just a few kilometres from the town of Anantnag, this elevated position serves a dual purpose that is central to the temple’s function and symbolism.

Architecturally, the plateau acts as a natural pedestal (jagati), elevating the sacred precinct above the surrounding agrarian plains. This ensures that the structure is visible from great distances, asserting the dominance of the solar deity and the terrestrial authority of the monarch who commissioned it. Conversely, from the temple precincts, visitors are afforded a panoramic view of the entire Kashmir Valley. Early European explorers and archaeologists, such as Alexander Cunningham, described this vista as “perhaps the finest view in the known world”.12 The sweeping gaze encompasses the lush green plains, the meandering Liddar River, and the snow-capped Pir Panjal range in the distance, creating a backdrop of sublime natural beauty that complements the man-made grandeur of the stone.13 This interplay between the constructed monument and the natural amphitheatre reinforces the connection between the macrocosm (the universe) and the microcosm (the temple).

The Etymology and Theology of “Martand”

The deity enshrined within the temple is Surya, the Sun God, but specifically in the form of Martand. The etymology of this name offers deep insight into the theological underpinnings of the site. Martand is derived from the Sanskrit compound Mrit-Anda, translating literally to “Dead Egg” or “Lifeless Bird”.6

In Vedic and Puranic mythology, this refers to the legend of Aditi, the mother of the gods (Adityas). It is said that Aditi gave birth to a “lifeless egg”, which she initially cast aside. However, this egg subsequently sprang to life as the Sun, the majestic celestial fire. The concept of the “Dead Egg” is rich in solar symbolism: it represents the sun that has “died” (set) at dusk, sinking into the darkness of the netherworld, only to be miraculously “reborn” (rise) at dawn. Thus, Martand is the sun of the resurrection, the deity who conquers darkness and death each morning.15 This aspect of the sun as a cyclical force of creation, dissolution, and regeneration was particularly potent in the Kashmiri Shaivite and Vaishnavite contexts, where the sun was often seen as a visible manifestation of the supreme consciousness.

The Sacred Hydrology: Springs and Rivers

The site itself, known locally as Mattan (a corruption of Martand), has been a Tirtha (pilgrimage site) since antiquity, long before Lalitaditya’s stone structure was raised. The Nilamata Purana, the ancient text on the history and geography of Kashmir, references this area as a sacred landscape dedicated to solar worship.15

Crucial to this sanctity is the presence of water. Just a few kilometres from the temple ruins lies the Mattan Spring (Bawan), a holy spring filled with sacred fish, which is still a centre of pilgrimage today.15 In the ancient design of the Martand complex, water was not just a nearby amenity but an integral architectural element. The temple complex originally featured a sophisticated hydraulic system that diverted water from the Liddar River via a canal running along the mountainside. This water was used to fill the vast courtyard of the temple, likely to a level that submerged the base of the columns.4

The effect of this engineering feat would have been theological as well as aesthetic. The main shrine, rising from the water, would have appeared to float on a “cosmic ocean,” replicating the primal waters of creation from which the Golden Egg (Hiranyagarbha or Martand) emerged. The still water would have acted as a mirror, reflecting the temple and the sky, symbolically merging the heavens with the earth and amplifying the solar light.4 This integration of river water (Liddar) and solar architecture underscores the advanced understanding of landscape manipulation possessed by the Karkota engineers.

The Imperial Vision: Lalitaditya Muktapida and the Karkota Zenith

The Expansionist Emperor

The construction of the Martand Sun Temple is inextricably linked to the persona of Lalitaditya Muktapida, the third and most formidable ruler of the Karkota Dynasty, who reigned from approximately 724 to 761 CE.1 Lalitaditya is often referred to by historians as the “Alexander of Kashmir” or the “Napoleon of India” due to his extensive military conquests and the sheer scale of his ambition.

Historical chronicles, particularly Kalhana’s Rajatarangini, describe Lalitaditya as a Digvijaya—a world conqueror. His empire is said to have stretched from Kabul and the Gandhara regions in the west to Bengal in the east, and from Kashmir down to the Konkan coast in the south.2 While modern historians debate the exact boundaries of his direct political control versus his sphere of influence, there is no doubt that he was the paramount power in Northern India during the 8th century. His armies traversed the diverse landscapes of Central Asia and the Indian plains, bringing back not only wealth and tribute but also artists, scholars, and architectural ideas.3

Lalitaditya’s reign marked a “Golden Age” for Kashmir. The immense wealth garnered from his campaigns allowed for a flourishing of arts, architecture, and literature. He was a prodigious builder, founding the new capital city of Parihaspora (“City of Smiles”) and commissioning numerous temples, chaityas, and viharas.2 His court was a cosmopolitan hub that attracted talent from across the known world, including China, Tibet, and the Tocharian regions. This exposure to diverse cultures is visibly reflected in the eclectic architectural style of the Martand Temple, which serves as a stone embodiment of his internationalist policy.3

Political Theology and the Solar Dynasty

The construction of the Martand Sun Temple was likely driven by a potent mix of genuine religious devotion and astute political messaging. By dedicating a colossal monument to Surya, the supreme celestial sovereign, Lalitaditya was asserting his own status as a Chakravartin—a universal wheel-turning monarch.13

In many ancient cultures, including the Vedic tradition, the king was seen as the earthly representative of the sun; just as the sun illuminates and rules the sky without rival, the emperor illuminates and rules the earth. The Karkota dynasty claimed lineage from the Nagas, but by adopting the solar cult so visibly, Lalitaditya may have been aligning himself with the prestigious Suryavansha (Solar Dynasty) of Indian mythology, the lineage of Lord Rama.18

Furthermore, the scale of the temple served to legitimise the Karkota dynasty’s power. It demonstrated the state’s ability to mobilise vast resources—labour, stone, and skilled craftsmanship—for a public and religious cause. The temple functioned not just as a place of worship but as a statement of imperial power, designed to awe subjects and rivals alike. It was a “State Temple” in the truest sense, where the worship of the deity and the veneration of the king were subtly intertwined.13

Architectural Synthesis: The “Kashmiri Style”

The architecture of the Martand Sun Temple is its most distinguishing and celebrated feature. It does not fit neatly into the standard Nagara (North Indian) or Dravida (South Indian) categories that dominate the architectural history of the subcontinent. Instead, it represents the pinnacle of a distinct “Kashmiri Style,” which is a syncretic blend of various international influences facilitated by Kashmir’s position on the Silk Road.4

The Hellenistic Imprint: Greek and Roman Echoes

One of the most striking aspects of the temple, which stunned early European archaeologists, is the strong presence of Classical Greco-Roman architectural elements. The visual vocabulary of Martand often feels closer to the Temple of Hercules in Rome or the Parthenon in Athens than to the temples of Varanasi or Bhubaneswar.4

- The Peristyle (Colonnaded Courtyard): The temple is surrounded by a massive colonnaded courtyard, or peristyle, measuring 220 feet by 142 feet. This feature is distinctively Greek in origin. The rectangular arrangement of columns creates a structured, rhythmic boundary around the sacred space, a layout common in Greek temples but rare in the Indian plains during this period, where enclosure walls (Prakaras) were generally plain or less dominant.6 Martand possesses the largest peristyle in Kashmir, boasting 84 fluted columns.4

- Columns and Capitals: The columns are fluted (having vertical grooves running down the shaft), a hallmark of the Greek Doric and Ionic orders. They support capitals that are reminiscent of the Corinthian order but modified with Indian motifs. This fusion creates a sense of soaring verticality and ordered symmetry.4

- Triangular Pediments: Above the doorways and niches, the temple features triangular pediments—the triangular upper part of the front of a building in classical style. These pediments give the structure a distinctively “European” silhouette, yet they house statues of Hindu deities, creating a fascinating cross-cultural tableau.4

The Gandharan Interface

While the “Greek” influence is visually dominant, scholars argue that it is not a direct import from the Mediterranean but rather mediated through the lens of Gandhara. The region of Gandhara (modern-day northwest Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan) was a melting pot where Hellenistic art met Buddhism following the conquests of Alexander the Great and the subsequent Indo-Greek kingdoms.

The “Greco-Buddhist” art of Gandhara heavily influenced Kashmiri artists. The naturalistic modelling of the figures, the drapery of the clothing (resembling togas or heavy cloaks), and the anatomical precision in the sculptures at Martand can be traced back to this lineage.13 The “Classical” aspect of Gandharan art, which persisted in Kashmir long after it faded elsewhere, allowed for the seamless integration of Western forms with Indian spirituality.

The Gupta and Indian Inheritance

Simultaneously, the temple exhibits strong Gupta influences from the Indian mainland. The Gupta period (c. 320–550 CE) is considered the classical age of Indian art, known for its idealised figures, spiritual serenity, and intricate floral motifs.

- Plan and Sanctum: The layout of the garbhagriha (sanctum) and the iconography of the Hindu deities reflect the standardisation of Hindu temple architecture that occurred during the Gupta era. The concept of the Mandapa (hall) and the Antarala (vestibule) are drawn from the developing canons of North Indian temple architecture.4

- Sculptural Style: While the “toga-like” dress may be Gandharan, the sensual modelling of the bodies, the tribhanga (three-bend) poses of the minor deities, and the elaborate jewellery reflect the Gupta aesthetic sensibility.5

Chinese and Central Asian Implications

Historical records indicate that Lalitaditya had diplomatic relations with the Tang Dynasty of China, even receiving investiture from the Chinese emperor. While less visually obvious than the Greek or Gupta elements, scholars suggest that the sheer scale of the complex and certain arrangements of the spaces may reflect Chinese spatial concepts. The enclosed, fortress-like nature of the courtyard and the strict axial alignment have parallels in Chinese palace architecture of the Tang period.2 Additionally, the steep pyramidal roof (now lost but reconstructed in drawings) was designed to shed the heavy snows of Kashmir, a functional necessity shared with the architecture of the Himalayas and East Asia.16

Structural Anatomy of the Complex

The Martand Sun Temple complex is massive, constructed primarily of grey limestone and sandstone, which gives it a sombre yet majestic appearance, especially when contrasted against the blue Kashmiri sky.5 The complex is arranged in a rectangular plan, measuring approximately 220 feet in length and 142 feet in breadth, making it one of the largest temple complexes in the region.4

The Courtyard and Peristyle: The Sacred Enclosure

The heart of the complex is the vast courtyard, originally paved with large stone slabs. Surrounding this courtyard is the peristyle—a colonnade of 84 fluted pillars. These pillars created a covered walkway for circumambulation (Parikrama) and sheltered visitors from the harsh sun or snow.3

- The Symbolism of 84: The choice of 84 pillars (and the corresponding 84 smaller shrines located within the colonnade) is highly significant in Hindu cosmology. In numerology, 84 is a sacred number (represented by the concept of Chaurasi). It is believed to represent the product of the 12 signs of the Zodiac and the 7 days of the week ($12 \times 7 = 84$), linking the architecture directly to the movement of time and the solar cycle. This reinforces the temple’s function as a cosmic clock, tracking the journey of the Sun God through the heavens.4

The Central Shrine (Vimana)

Rising from the centre of the courtyard is the main shrine. It stands on a high plinth and was originally much taller, likely reaching a height of around 75 feet. It was capped with a pyramidal roof made of stone—a common feature in Kashmiri temples designed to withstand heavy snowfall, distinct from the curvilinear Shikharas of the Indian plains.4

The central structure is divided into three distinct spatial zones:

- Ardha Mandapa: The entrance porch, which serves as a transitional space between the outer world and the sacred interior.

- Antarala: The antechamber or vestibule. This space features intricate carvings of deities and serves as the assembly area for the priests or royalty.

- Garbhagriha: The inner sanctum sanctorum, a square chamber where the primary idol of the Sun God was once enthroned. This space was the spiritual heart of the temple, likely illuminated by the first rays of the rising sun.11

The Gateway (Praveshdvara)

The entrance to the temple is on the western side, aligned so that the rising sun from the east would illuminate the idol in the sanctum. The gateway itself is a monumental structure, mirroring the width of the main temple, creating a sense of symmetry and grandeur. It is adorned with elaborate carvings and niches that once held images of gods and goddesses, acting as a prelude to the divine encounter inside.6

Materiality and Construction Techniques

The temple is built using huge blocks of limestone, known locally as Devri stone. These blocks were joined using iron dowels and lime mortar, a technique that provided immense structural stability. The ashlar masonry (precisely cut and dressed stones) is of a high order, with the joints often being barely visible. The use of such massive stones, some weighing several tons, speaks to the sophisticated logistical capabilities of the Karkota administration.5

Iconography and Artistic Motifs

The artistic embellishments of the Martand Sun Temple are a testament to the skill of 8th-century Kashmiri sculptors. Despite the defacement caused by iconoclasm and weathering, the surviving reliefs provide a glimpse into the rich theological tapestry of the time.

Solar Iconography

As a solar temple, the primary imagery is that of Surya. Although the central idol is missing—believed to have been made of gold or copper and possibly taken or destroyed during the plunder—reliefs on the walls depict the Sun God. Surya is traditionally shown in his chariot, the celestial vehicle that traverses the sky. He is pulled by seven horses, which represent the seven colours of the visible spectrum (the rainbow) or the seven days of the week. Aruna, the charioteer (and personification of dawn), drives the horses, symbolising the light that precedes the sun.14

Vaishnavite and River Goddess Imagery

The antechamber walls feature prominent carvings of other deities, indicating a syncretic approach or the Panchayatana style of worship (where the main deity is surrounded by four subsidiary deities).

- Vishnu: There are depictions of a multi-headed Vishnu, likely the Vaikuntha Chaturmurti form, which was highly popular in Kashmir. This form combines the human face of Vishnu with the faces of a lion (Narasimha) and a boar (Varaha). This signifies the close relationship between solar worship and Vaishnavism, where Surya is often considered an aspect of Vishnu (Surya-Narayana).11

- River Goddesses: Images of Ganga and Yamuna, the personifications of India’s holiest rivers, flank the entrance to the sanctum. Standing on their respective vehicles (the crocodile and the tortoise), these figures are a classic Gupta-era motif, symbolising purification. Passing between them represents a ritual cleansing before entering the sacred space of the Garbhagriha.11

- Brahma and Others: A four-armed sculpture of Brahma has also been noted, adding to the complexity of the pantheon represented. The presence of these diverse deities suggests that while the temple was solar-centric, it embraced the broader Hindu pantheon.5

Stone and Style: The “Cold” Aesthetic

The sculptures are carved in high relief on the limestone blocks. The figures are robust, with broad shoulders and narrow waists (Gupta influence), but their clothing—tunics, cloaks, and boots—reflects the Central Asian and Gandharan influence. This attire was suitable for the cold climate of Kashmir, unlike the scantily clad figures seen in temples of tropical India. This “Cold Aesthetic” is a unique marker of Kashmiri art, grounding the divine figures in the local geography.12

The Cataclysm: History and Historiography of Destruction

The ruinous state of the Martand Sun Temple is the result of a deliberate and catastrophic intervention in the 15th century. While natural factors like earthquakes have contributed to its degradation, historical consensus points to a systematic campaign of destruction that effectively ended the temple’s life as a functioning place of worship.

Sultan Sikandar “Butshikan”

The primary agent of destruction was Sultan Sikandar Shah Miri (ruled 1389–1413), the sixth sultan of the Shah Mir dynasty. He is infamously known in history as Sikandar Butshikan (Sikandar the Idol-Breaker). The historical narrative suggests that Sikandar, driven by a zeal to Islamize the Kashmir Valley, acted on the advice of the Sufi preacher Mir Muhammad Hamadani and his prime minister, Suhabhatta (a Brahmin convert to Islam who took the name Malik Saif-ud-Din).1

Historical chronicles such as the Rajatarangini of Jonaraja (a contemporary of Sikandar) and the later Persian chronicle Baharistan-i-Shahi record that Sikandar unleashed a reign of terror against the Hindu population, which included the destruction of temples, the burning of scriptures, and forced conversions. Martand, being the most prominent and grandest symbol of the old faith, was a primary target.7

The Mechanics of Destruction: Fire and Timber

The destruction of the Martand Sun Temple was not a simple act of vandalism; it was a major engineering project in reverse. Legends and oral histories, supported by some historical analysis, suggest that the temple was so massive and sturdily built that it took a dedicated workforce an entire year to dismantle it. The massive limestone blocks were too heavy to be easily toppled, and the iron dowels held them fast.

A persistent account describes the “Fire Method” employed by the destroyers. Unable to demolish the walls with hammers and chisels alone, they filled the sanctum and the spaces between the walls with vast quantities of timber and wood. They then set the timber on fire. The intense heat generated by the bonfire acted on the limestone (calcium carbonate), causing it to expand, crack, and crumble. Once the structural integrity of the stone was compromised by the heat, the walls were pushed down, and water may have been thrown on the hot stones to fracture them further.7 This method explains the blackened state of some of the stones visible today and the thoroughness of the ruin.

Scholarly Debate: Realpolitik vs. Fanaticism

While medieval chroniclers explicitly blame Sikandar for the destruction, some modern scholars offer nuanced interpretations of his motivations.

- Political Economy: Historians like Chitralekha Zutshi and Richard G. Salomon argue that Sikandar’s iconoclasm may have been driven by realpolitik rather than just religious fanaticism. The Hindu temples of Kashmir were wealthy institutions, controlling vast tracts of land and treasure. By destroying the temples, the Sultan was asserting state power over the Brahminical elite and seizing their wealth to finance his own state-building. Delegitimising the Hindu structures was a way to legitimise the new Islamic Sultanate.6

- Earthquakes: It is also acknowledged that Kashmir is a seismically active zone. Earthquakes over the centuries have undoubtedly exacerbated the damage, toppling already weakened walls and pillars. However, the systematic defacement of images and the specific nature of the structural collapse—where the central shrine is stripped, but the surrounding cells are less damaged—suggest that human agency was the primary cause of the temple’s demise.6

Rediscovery and Heritage Status

After centuries of neglect, where the ruins were often used as a quarry by locals or merely stood as a ghostly reminder of the past, the 19th century brought renewed interest in the site.

European Documentation

British surveyors and archaeologists, exploring the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, were struck by the ruins. Sir Alexander Cunningham, the founder of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), visited the site in the mid-19th century. He was the first to systematically document the layout and link it to the descriptions in the Rajatarangini. In 1870, J. Duguid created restored impressions and drawings of what the temple might have looked like in its prime, helping to visualise the lost pyramidal roof and the full height of the structure.6 These early documentations are crucial today for understanding the original scale of the monument and for any potential restoration efforts.

ASI Protection and Legal Status

In the 20th century, the Archaeological Survey of India designated the Martand Sun Temple as a “Site of National Importance.” It was brought under the list of centrally protected monuments, officially listed as “Kartanda (Sun Temple)”.1 This status legally protected the site from further encroachment and mandated its conservation. However, the tumultuous political history of Kashmir in the late 20th and early 21st centuries often hampered effective on-site management, leaving the temple in a state of “preserved ruin.”

The Contemporary Battlefield: Heritage vs. Practice (2022-2025)

In recent years, the Martand Sun Temple has become a flashpoint for religious and political assertion, challenging the secular and preservationist mandates of the ASI. The ruins have transitioned from a quiet archaeological site to a contested space of living heritage.

The Puja Controversies (2022-2024)

The ruins have seen a resurgence of religious activity, leading to friction between devotees and the ASI.

- May 2022 Event: A major controversy erupted when Jammu and Kashmir Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha participated in a “Navgrah Ashtamangalam Puja” at the temple premises. The ASI raised concerns, stating that no permission was sought for the ritual. ASI rules typically prohibit religious prayers at “non-living” monuments (sites where worship was not active at the time of protection). However, the J&K administration argued that Rule 7(2) of the 1959 Ancient Monuments Act allows for “recognised religious usage and custom,” creating a legal grey area regarding what constitutes “customary” usage for a temple that has been in ruins for centuries.8

- January 2024 Entry: On January 22, 2024, coinciding with the consecration of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya, members of a group called “Rashtriya Anhad Mahayog Peeth” entered the temple to hold prayers. Despite the ASI staff’s attempts to stop them, they performed a circumambulation and chanted the Hanuman Chalisa. This was the third consecutive year this group attempted to assert religious rights over the monument, signalling a growing movement to “reclaim” the site for active worship.8

- The “Kalash” Installation: In a symbolic move linking the Kashmiri site to the broader pan-Indian religious narrative, a ‘Kalash’ (sacred pot) from Ayodhya was installed at a Ram Temple located within the precincts or immediate vicinity of the Sun Temple complex in January 2024.10

The “Living” vs. “Dead” Monument Debate

These events highlight a core conflict in heritage management in India. The ASI views the Martand Temple as an archaeological ruin—a “dead” monument—to be preserved for its historical, artistic, and secular value. Its priority is the physical integrity of the structure. Conversely, many in the Kashmiri Pandit community and Hindu groups view it as a sacred Tirtha that was forcibly desecrated. They argue that the “non-living” status is a result of persecution and that their right to worship should be restored. They contend that a temple, once consecrated, remains a temple forever, regardless of its physical state.9

Restoration and Future Prospects: A New Era?

As of 2024 and heading into 2025, the trajectory of the Martand Sun Temple is shifting from passive preservation to active restoration and ideological reclamation.

Government Notification (March 2024)

In March 2024, the Jammu and Kashmir government issued a notification announcing a high-level meeting to discuss the “protection, conservation, and restoration” of ancient temples in Kashmir, specifically naming the Martand Sun Temple. This signals a major policy shift, potentially moving towards reconstructing parts of the temple or at least stabilising it more aggressively than in the past. This initiative is seen by some as a move to restore the cultural dignity of the region’s minority community.9

Statue of Lalitaditya Muktapida

A significant and symbolic component of the new plan is the proposal to install a statue of Emperor Lalitaditya Muktapida within the temple premises. This move aims to reclaim the historical narrative of the Karkota dynasty and honour the builder of the monument. It represents a state-led effort to re-anchor the site in its Hindu-Kashmiri origins and celebrate Lalitaditya as a national hero.10

Technical Challenges of Restoration

Restoration is fraught with difficulty. The original stones are massive, and many are missing or damaged beyond repair. Rebuilding a temple of this scale requires not just funds but archaeological precision to avoid creating a “Disneyfied” version of history. The ASI and experts will likely have to navigate the fine line between anastylosis (reassembling existing parts) and reconstruction. Any attempt to rebuild the pyramidal roof or the superstructure would be hypothetical and controversial among conservationists.30

Cultural Resonance: Pop Culture and Tourism

The Martand Sun Temple occupies a unique space in the cultural imagination of India, bridging the gap between ancient history and modern pop culture.

Bollywood and Visual Media

The haunting beauty of the ruins has made it a favoured location for filmmakers, who use the site to evoke themes of tragedy, grandeur, and loss.

- Haider (2014): Vishal Bhardwaj’s adaptation of Hamlet featured the temple prominently in the song “Bismil.” The dramatic performance, with the ruins serving as a theatre of tragedy, brought the site to the attention of a younger generation. However, it also sparked some controversy regarding the depiction of the site as a “Devil’s Den” in the film’s narrative context, though the visual grandeur was undeniable.31

- Aandhi (1975): The classic song “Tere Bina Zindagi Se Koi Shikwa To Nahin” was filmed here. The juxtaposition of the estranged lovers against the broken ruins created a powerful visual metaphor for a relationship that was beautiful yet fractured.18

- Man Ki Aankhen: Another film that utilised the backdrop of the temple, showcasing its enduring appeal as a cinematic location.5

These cinematic representations have played a crucial role in boosting tourism. Visitors often come to see the “Haider location,” providing an opportunity to educate them about the deeper history of Lalitaditya and the Sun God.33

Tourism Potential

The site is a major tourist attraction in the Anantnag district. Its proximity to Pahalgam makes it an accessible detour for tourists visiting the valley. However, infrastructure remains a challenge. The recent government push aims to improve amenities, hoping to integrate heritage tourism with the religious pilgrimage circuits of the valley, such as the Amarnath Yatra.5

Comparative Analysis with Other Sun Temples

To fully appreciate the Martand Sun Temple, it must be viewed in the context of other major Sun temples in the Indian subcontinent. It stands as the northern sentinel of solar worship, contrasting with the eastern and western expressions of the same cult.

| Feature | Martand Sun Temple (Kashmir) | Konark Sun Temple (Odisha) | Modhera Sun Temple (Gujarat) | Multan Sun Temple (Pakistan) |

| Date | 8th Century CE | 13th Century CE | 11th Century CE | Ancient (Destroyed) |

| Builder | Lalitaditya Muktapida | Narasimhadeva I | Bhima I | (Various legends) |

| Style | Kashmiri (Gandharan/Greek blend) | Kalinga (Orissan) | Maru-Gurjara (Chalukyan) | — |

| Key Feature | Peristyle (Colonnaded courtyard) | Chariot form with wheels | Stepped Tank (Surya Kund) | Gold Idol (Lost) |

| Status | Ruined | Partially Ruined (UNESCO Site) | Partially Ruined | Completely Lost |

| Roof Type | Pyramidal (Stone) | Curvilinear (Shikara) | Curvilinear (Lost) | — |

Analysis:

- Chronology: Martand is the oldest among the grand medieval Sun temples, predating Modhera by three centuries and Konark by five. It represents an earlier phase of solar architecture.

- Form: While Konark is famous for its literal representation of a chariot with stone wheels, Martand implies the chariot through its iconography but focuses on the enclosure (peristyle) and the elevation (pyramid).

- Fate: Like the Multan Sun Temple (which was famously destroyed), Martand suffered total iconoclasm. In contrast, Konark’s ruin was largely due to structural failure and neglect, though it also faced invasions.13

Conclusion

The Martand Sun Temple is a monument of paradoxes. It is a ruin that speaks of impermanence, yet its massive limestone walls have outlasted empires and dynasties. It is a site of deep religious devotion that was silenced by religious intolerance. It is a masterpiece of “Indian” art that looks strikingly “Greek.”

The legacy of Lalitaditya Muktapida’s creation is enduring. It serves as a vital historical document, recording the syncretic culture of 8th-century Kashmir where East and West met under the banner of the Sun God. It reminds us that Kashmir was once the intellectual and political centre of North India, a land where the boundaries of the known world dissolved in the pursuit of beauty and the divine.

The destruction by Sikandar Butshikan, while tragic, has inadvertently added a layer of sombre historical gravity to the site. The blackened stones and the headless deities are not just debris; they are witnesses to the fragility of heritage in the face of fanaticism. They force the viewer to confront the violent ruptures of history.

As we move through the 2020s, the Martand Sun Temple is entering a new phase of its existence. The efforts to restore it and the debates over its religious use reflect a broader struggle to reconcile the past with the present in Kashmir. Whether it remains a protected ruin or becomes a living shrine once more, the Martand Sun Temple stands as the “Sun of Kashmir.” Like the Martand of mythology—the dead egg that springs to life—the temple seems poised for a resurrection, not necessarily of its roof, but of its place in the consciousness of the nation.

Disclaimer

This report is based on the research material provided, including historical texts, archaeological reports, and news articles up to late 2024 and early 2025. Historical interpretations, particularly regarding the specific motivations for destruction (religious vs. political) and the extent of the Karkota empire, are subject to ongoing scholarly debate. Mentions of recent political events, religious controversies, and restoration plans reflect the available data at the time of writing and do not constitute an endorsement of any specific political or religious viewpoint. The analysis of “current” status refers to the situation as described in the provided snippets.

Reference

- Traces of Martand Sun Temple of Kashmir Valley: An Architectural Study – ijrpr, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://ijrpr.com/uploads/V5ISSUE2/IJRPR22687.pdf

- IAS – AWS, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://next-ias-appsquadz.s3.ap-south-1.amazonaws.com/file_library/pdf/original/335124830404640060_PDF_ORIGINAL.pdf

- Martand Sun Temple- Builders and Destroyers- A Historical Exploration – India’s Biggest Dashakarma Bhandar | Poojn.in, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.poojn.in/post/17045/martand-sun-temple-builders-and-destroyers-a-historical-exploration

- Martand Sun Temple: An exposition of the Architectural Features – IJNRD, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.ijnrd.org/papers/IJNRD2301283.pdf

- Anantnag Martand Sun Temple- Ancient Marvel Of Kashmir – Incredible India, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.incredibleindia.gov.in/en/jammu-and-kashmir/anantnag/martand-sun-temple

- Martand Sun Temple – Wikipedia, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martand_Sun_Temple

- Destruction of Martand Temple in Kashmir – HinduPost, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://hindupost.in/dharma-religion/destruction-of-martand-temple-in-kashmir/

- Despite ASI attempts, saffron outfit once again forces entry into J&K Martand sun temple, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.nationalheraldindia.com/national/despite-asi-attempts-saffron-outfit-once-again-forces-entry-into-anantnag-martand-sun-temple

- Martand Sun Temple: J&K Govt set to restore historic temple destroyed by Sikandar Butshikan for Islamisation of Valley – HinduPost, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://hindupost.in/dharma-religion/martand-sun-temple-jk-govt-set-to-restore-historic-temple-destroyed-by-sikandar-butshikan-for-islamisation-of-valley/

- J&K govt to restore 8th century Martand Sun temple in Anantnag. All you need to know – Mint, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.livemint.com/news/india/martand-sun-temple-in-anantnag-jammu-and-kashmir-j-k-govt-restore-lalitaditya-muktapida-all-you-need-know-lg-manoj-sinha-11711799132696.html

- Martand Sun Temple – The Travel Talk, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://thetraveltalk.net/monuments_detail/133

- The Martand Surya Temple of Kashmir: A Legacy Lost – Critical Collective, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://criticalcollective.in/ArtHistoryDetail.aspx?Eid=587

- Martand Sun Temple UPSC – IAS Gyan, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.iasgyan.in/daily-current-affairs/martand-sun-temple-18

- Martand Surya Temple, Pahalgam – Backpackers United, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://backpackersunited.in/destinations/pahalgam/attraction/martand-surya-temple

- Ancient Martand Sun Temple near Anantnag in Kashmir – Inditales, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://inditales.com/ancient-martand-sun-temple-near-anantnag-in-kashmir/

- Martand, Kashmir – Reminiscing History, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.reminiscinghistory.com/work-of-art/kashmir

- Discover the Secrets of Martand Sun Temple – Radisson Hotels, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.radissonhotels.com/en-us/blog/art-culture/martand-sun-temple

- accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.tripoto.com/india/trips/martand-sun-temple-the-pride-of-kashmir-now-in-ruins-59672b0d3c317#:~:text=Famous%20song%20Tere%20bina%20zindagi,map%20of%20Jammu%20and%20Kashmir.

- Sun Temple, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://go2kashmir.com/place-of-interest/sun-temple-details.html

- Gandharan art and the classical world: a short introduction – Bryn Mawr Classical Review, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2024/2024.10.37/

- Martand Sun Temple – Brown Chinar Tour And Travel, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://brownchinarkashmir.com/martand-sun-temple/

- Sikandar Shah Miri – Wikipedia, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sikandar_Shah_Miri

- Martand Sun Temple was destroyed by Sikander Butshikan. It is said that the temple was so strong and beautiful that it took him one full year to completely destroy it. After many failed attempts, he stuffed the temple’s walls with wooden slippers and set them on fire : r/IndiaNonPolitical – Reddit, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/IndiaNonPolitical/comments/iygxy5/martand_sun_temple_was_destroyed_by_sikander/

- Martanda (Sun) temple), what it is and what it used to be. : r/hinduism – Reddit, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/hinduism/comments/1i3fb8i/martanda_sun_temple_what_it_is_and_what_it_used/

- Puja event at ASI-protected Martand Temple in Kashmir stokes controversy – The Hindu, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/puja-event-at-asi-protected-martand-temple-in-kashmir-stokes-controversy/article65398937.ece

- Archaeological Survey vs J&K Administration Over Puja At Protected Martand Sun Temple, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/archaeological-survey-vs-j-k-administration-over-puja-at-protected-martand-sun-temple-2960935

- Hindu Group Forces Entry Into ASI-Protected Martand Sun Temple In Kashmir: Report, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://kashmirtimes.com/jammu-and-kashmir-news/martand-sun-temple-complex

- Martand Sun Temple: J&K Govt set to restore historic temple destroyed by Sikandar Butshikan for Islamisation of Valley, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://organiser.org/2024/03/30/230112/bharat/martand-sun-temple-jk-govt-set-to-restore-historic-temple-destroyed-by-sikandar-butshikan-for-islamisation-of-valley/

- JK Admin Plans Lalitaditya Statue at Martand Temple – Kashmir Life, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://kashmirlife.net/jk-admin-plans-lalitaditya-statue-at-martand-temple-349430/

- Restoration of Martand Sun Temple, Kashmir – Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.heritageuniversityofkerala.com/JournalPDF/Volume8.2/60.pdf

- accessed on December 9, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haider_(film)#:~:text=The%20last%20filming%20schedule%20of,been%20used%20in%20’Bismil’.

- ‘Haider’ – Times of India, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/haider/photostory/64155007.cms

- 10 Years of Haider: How ‘Bismil’ sparked a tourism boom at Martand Sun Temple; haunting song from Shahid Kapoor-starrer also holds a Sanjeev Kumar connection 10 – Bollywood Hungama, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.bollywoodhungama.com/news/features/10-years-haider-bismil-sparked-tourism-boom-martand-sun-temple-haunting-song-shahid-kapoor-starrer-also-holds-sanjeev-kumar-connection/

- Martand Sun Temple (2025) – Best of TikTok, Instagram & Reddit Travel Guide, accessed on December 9, 2025, https://www.airial.travel/attractions/mattan/martand-sun-temple-8d9D724V