Introduction: The Glimmer and the Grit

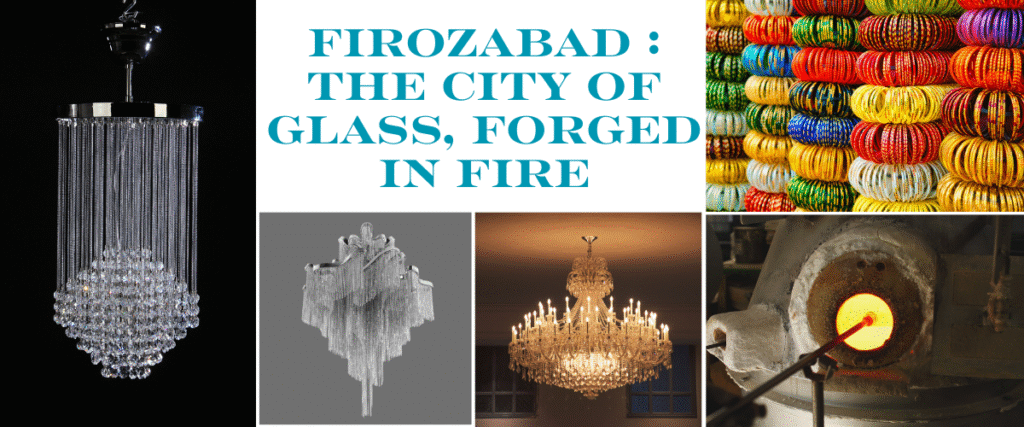

On the wrist of a bride, they are circles of joy, shimmering with colour and light. In the grand hall of a palace, a chandelier descends like a frozen waterfall of crystal, a testament to exquisite artistry. This is the luminous world of Firozabad glass—a world of delicate beauty, vibrant hues, and timeless tradition. For centuries, this city in Uttar Pradesh, located just 40 kilometres from Agra, has been India’s undisputed capital of glass, its name synonymous with the bangles that adorn millions and the intricate glassware that graces homes across the globe.1 It is affectionately known as the Suhag Nagri, the city that fulfils the demands of married women, and the city that has “glittered for centuries”.3

But behind this glimmer lies the grit. The story of Firozabad is a profound paradox, a tale of two cities intertwined. One is a city of celebrated heritage and immense economic output; the other is a city of searing heat, toxic fumes, and crushing hardship. The same fire that melts glass into liquid light also scorches the lungs of the artisans who tend it. The hands that deftly shape molten art are often ungloved, underpaid, and unprotected.5 Firozabad is a city forged in fire, and its identity is a complex alloy of beauty and suffering, tradition and exploitation, wealth and poverty. To truly understand this City of Glass, one must look beyond the finished product and into the heart of the inferno where it is born. What, then, is the true cost of this glittering heritage?

A City Named in Conquest, An Industry Born from Scraps

The identity of Firozabad is built on layers of history, with narratives of conquest and ingenuity that continue to shape its present. The city’s very name is a relic of Mughal administrative might. Formerly known as Chandwar Nager, a stronghold of the Chauhan Rajputs, it was renamed in 1566 by Firoz Shah Mansabdar, a military officer dispatched by Emperor Akbar to restore order and suppress local uprisings.1 This act cemented the region’s place within the Mughal empire, and its strategic position on the vital trade route between Agra and the eastern territories fueled its early development as an administrative and commercial centre.7

While the city’s political origins are well-documented, the genesis of its defining industry is shrouded in multiple, often conflicting, narratives. These different stories are more than just historical curiosities; they represent a fundamental tension in Firozabad’s identity. One version credits the craft to elite, imported artistry under royal patronage. Some accounts suggest Emperor Akbar established a glass factory in the 16th century, while others claim it was Emperor Shah Jahan who, in the 17th century, brought skilled glassmakers from Persia and Syria to create opulent glassware for the imperial court.2 This narrative elevates the craft, linking it to a legacy of royal prestige and sophisticated, external expertise.

In stark contrast, a more organic, grassroots origin story grounds the industry in local resourcefulness and resilience. According to this tradition, the craft began when early invaders brought glass articles to the city. When these items were eventually rejected and discarded, local people collected the broken shards and, in an act of profound ingenuity, melted them down in primitive, locally made furnaces known as Bhainsa Bhatti.4 This narrative posits that the industry was not imported but born from the scraps of conquest, fueled by the cleverness of the common person. This theme of recycling remains a cornerstone of the industry to this day.12

This duality in its origin—a craft of kings versus a craft of commoners—is not merely an academic debate. It speaks to the complex social fabric of Firozabad and influences the “craft consciousness” of the artisans themselves.13 It shapes how they perceive their own value: as inheritors of a noble, ancient art form, or as resourceful labourers in a demanding, often brutal, industry.

From these humble or noble beginnings, the industry evolved. Early production focused on simple items like small bottles and seamless bangles called Kadechhal Ki Chudi.4 Over time, skills advanced, and Firozabad’s artisans began crafting elaborate chandeliers— jhad and fanus—for the drawing rooms of nobles and royal courts.4 The industry truly began to flourish during the British colonial era, benefiting from its proximity to newly laid railway lines that connected it to wider markets.7 It was during this period that Firozabad consolidated its identity, transforming from a historical settlement into a formidable industrial town, the undisputed centre of glass bangle production for over two centuries.3

The Alchemy of Glass: A Dance of Fire and Breath

To step inside a Firozabad glass workshop is to witness an alchemy that borders on the primal. It is a world of intense heat, rhythmic motion, and a symphony of synchronised skills passed down through generations of artisans, known as Kanchhkars.2 The creation of the city’s most iconic product, the glass bangle, is a multi-stage ballet of fire, breath, and human touch.

The process begins not with pristine raw materials, but with mountains of discarded glass. Firozabad is a massive hub for glass recycling in India; old bottles, broken windowpanes, and other glass waste form the base material, or cullet.8 This cullet is mixed with silica sand, soda ash, and a precise cocktail of chemicals and mineral oxides—lead, cobalt, cadmium—that will bloom into vibrant colours when subjected to the furnace’s fiery heart.3

This mixture is fed into furnaces, or bhattis, that burn around the clock at temperatures soaring between 1200°C and 1400°C.3 The workshops house different types of furnaces, from traditional, manually fed pot furnaces to more modern, gas-fired regenerative tank furnaces, each a roaring beast that transforms solid scrap into a glowing, honey-like liquid.14

From this molten state, the bangle is born through a series of rapid, fluid movements:

- An artisan, the gulliwala, dips a long iron blowpipe into the furnace, gathering a luminous glob of molten glass on its end.8

- He swiftly transfers it to another artisan who deftly shapes the glob into a cone.17

- From the tip of this cone, another craftsman draws out a thin, continuous filament of glass, its thickness controlled purely by the speed and tension of his pull.17

- This glowing thread is then expertly wound around a rotating iron rod, the muttha, forming a perfect, tightly-packed spiral of glass. An entire team works in seamless coordination; as one glob of glass is nearly exhausted, another is attached to maintain the continuity of the spiral.8

- Simultaneously, a worker at the other end uses a pointed tool to guide the filament, ensuring the coils are uniform and do not fuse together.17

- Once the muttha is full, the glowing spiral, which looks like a giant spring, is slid off. After cooling slightly, it is cut along its length with a diamond-tipped cutter, instantly separating the continuous coil into hundreds of individual, open-ended bangles.17

At this point, the process transitions from the factory floor to the labyrinthine lanes of Firozabad, into smaller workshops and private homes where the finishing touches are applied, often by women. In a process called Judai (joining), women sit before small flames, skillfully melting the open ends of each bangle and fusing them together to create a perfect circle.17 Following this, another set of artisans takes over for decoration. Plain bangles are transformed into works of art with intricate patterns of glitter (zari), enamel paint, mirror work, stones, and sometimes even delicate gold foil.3 The final step is a trip to the pakai bhatti, a baking furnace where the decorated bangles are gently heated one last time to smoothen any sharp edges and set the designs, giving them their final, brilliant lustre.17

While bangles are its most famous creation, Firozabad’s artisans are also masters of the mouth-blowing technique, a rare craft recognized under the government’s One District One Product (ODOP) initiative.7 Using this ancient method, artisans blow air through a pipe into a glob of molten glass, skillfully shaping it into vases, lamps, decorative figurines, and tableware, each piece a unique testament to the artist’s breath and skill.19

| Step Number | Process Name (Local Term) | Description of Action | Key Skills/Tools Involved | Location |

| 1 | Melting | Recycled glass, sand, and chemicals are melted at 1200−1400∘°C. | Furnace (bhatti) operation, knowledge of chemical composition. | Factory |

| 2 | Gathering & Shaping | A glob of molten glass is gathered on an iron pole and shaped into a cone. | Strength, heat resistance, shaping tools, and teamwork. | Factory |

| 3 | Drawing & Winding | A thin filament is drawn from the glob and wound around a rotating rod. | Hand-eye coordination, control of tension and speed, rotating rod (muttha). | Factory |

| 4 | Cutting | The cooled glass spiral is cut with a diamond cutter to separate bangles. | Precision cutting, diamond-tipped tool. | Factory |

| 5 | Joining (Judai) | The open ends of each bangle are fused together over a flame. | Dexterity, flame control, precision heating. | Home/Small Workshop |

| 6 | Decoration | Designs are added using paint, glitter, stones, and other materials. | Artistic skill, fine motor control, and various decorative materials. | Home/Small Workshop |

| 7 | Baking (Pakai Bhatti) | Decorated bangles are baked to smooth edges and set designs. | Temperature control, baking furnace. | Small Workshop |

The Economic Powerhouse of Suhag Nagri

The Firozabad glass industry is not merely a cultural heritage; it is a colossal economic engine that serves as the primary lifeline for an entire region. With an estimated annual turnover ranging from ₹10,000 crore to over ₹15,000 crore, the industry is a significant contributor to the state’s economy.20 It provides direct and indirect employment to more than 600,000 people, with some estimates suggesting that 90% of the city’s population relies on it for their income.20 The cluster is responsible for an astonishing 70% of the total glass produced by the unorganised sector in India, cementing its status as a manufacturing behemoth.23

While the city’s fame was built on the humble bangle, its economic survival has depended on aggressive diversification. The product range has expanded exponentially to include a vast array of goods: decorative glassware, tableware, jars and containers, scientific lab equipment, chandeliers, lamps, and even automotive components like headlights and bulbs.14 This shift reflects a strategic adaptation to changing markets. However, the most profound economic transformation has been the move towards large-scale, automated production of glass bottles. This segment, driven by massive demand from the alcohol, food, and cosmetics industries, now constitutes up to 80% of the total products manufactured in the city.21

This diversification represents a fundamental pivot in the industry’s character. The move from handmade, skill-intensive bangles to machine-made, high-volume bottles ensures robust economic growth and higher turnover. Yet, this very success simultaneously devalues the traditional, high-skill craftsmanship that is the city’s cultural hallmark. The economic health of Firozabad is becoming increasingly decoupled from its artisanal identity. The industry is growing richer, but the Kanchhkars who possess the centuries-old skills are being marginalised, their craft overshadowed by the relentless logic of mass production.8

Firozabad’s economic might extends globally, with roughly half of its production often destined for export markets.14 The United States is a particularly crucial partner, representing the largest buyer of Firozabad’s handcrafted decorative glassware, with exports to the US valued at over ₹1,400 crore annually.26 This deep reliance on international trade, however, makes the city’s economy exquisitely vulnerable to global shocks. The imposition of stiff 50% import tariffs by the US in recent years sent tremors through the industry, putting orders worth hundreds of crores on hold and threatening the livelihoods of countless exporters.26 Similarly, the 2022 economic crisis in Sri Lanka had a direct and damaging impact, leading to approximately ₹5 crore in defaulted payments and the cancellation of orders worth tens of crores.20 These episodes starkly illustrate the fragility of an economy so tightly woven into the unpredictable fabric of global politics and commerce.

Recognising its significance, the government has extended support through initiatives like Uttar Pradesh’s “One District One Product” (ODOP) scheme, which identifies Firozabad for its traditional glassware and aims to bolster the craft through financial and skill-based assistance.7

The People in the Inferno: Life and Livelihood in the Glass Factories

The human cost of Firozabad’s glass is etched onto the bodies and into the lungs of its artisans. The workshops, often described as “burn-houses” or “infernos,” are gruelling environments where workers endure conditions that push the limits of human tolerance.4 These small-scale units frequently lack basic ventilation or cooling systems, creating a claustrophobic atmosphere where temperatures can soar above 50°C in the summer months.30 Workers often operate without essential safety gear like gloves, face masks, or protective eyewear, leaving them perpetually exposed to the dual threats of severe burns from molten glass and injuries from sharp, broken pieces.5

This hazardous environment inflicts a devastating toll on the health of the workforce. The air itself is a toxic cocktail of fumes from the furnaces and the chemicals used for colouring the glass, which can include hazardous materials like lead, cadmium, arsenic, and nickel.6 This constant exposure leads to a host of severe health crises:

- Respiratory Illnesses: Studies have shown a significant reduction in lung function among workers, which worsens with the duration of exposure. Chronic bronchitis is rampant, affecting as many as 23% of the workforce, alongside high rates of bronchial asthma and other respiratory disorders.6

- Ocular Damage: The intense infrared radiation emanating from the furnaces causes a range of debilitating eye conditions. Workers suffer from chronic dry eye, itching, and redness, as well as more severe ailments like pterygium (a growth on the eye) and cataracts, a condition so common it is known as “glass blowers’ cataract”.33

- Heat-Related Illnesses: The historically intense heat of the workshops has been dangerously amplified by climate change, transforming a chronic hazard into an acute crisis. This is not an abstract future threat for Firozabad’s artisans; it is an immediate occupational reality. Rising global temperatures act as a “threat multiplier,” making the already unbearable heat impossible to endure. This has led to a dramatic increase in cases of heat exhaustion, severe dehydration, and life-threatening heatstroke, resulting in frequent hospitalisations.29 For workers earning as little as ₹300-₹500 a day, the cost of medical treatment for these illnesses can be financially ruinous.6

- Other Ailments: The physically demanding labour, often performed in cramped and awkward positions for long hours, leads to chronic musculoskeletal issues like backache and joint pain. Direct contact with colouring chemicals and glass dust also results in persistent skin infections.31

Within this landscape of hardship, women workers, particularly those in the decentralised, home-based sector, are the most vulnerable and exploited. Largely invisible to labour laws and official statistics, they form the backbone of the industry’s finishing processes.31 Women are overwhelmingly engaged in the lower-paid, yet essential, tasks of sorting bangles (Chaklai), joining them over open flames (Judai), and applying intricate decorations.6 They are paid on a piece-rate basis, earning wages far below the legal minimum, and are subject to the whims of middlemen who often make arbitrary deductions or delay payments.31 Lacking formal contracts, job security, or access to social security benefits, these women are trapped in a cycle of poverty and precarity. They also bear the double burden of this hazardous work and their traditional domestic responsibilities, leading to immense physical and psychological stress.34

Social hierarchy within the workshops is deeply tied to skill. Historically, the Muslim Sheeshgarh community was considered the master of the craft’s most valuable skills, creating a clear hierarchy among workers.13 The transmission of these skills—or the lack thereof—across caste and religious lines remains a central dynamic, defining communities of practice and shaping relationships between labourers, supervisors, and owners.13

A Fragile Ecosystem: Challenges at the Crossroads

The Firozabad glass industry stands at a precarious crossroads, beset by an interconnected web of economic, environmental, and social challenges that threaten its very survival. These are not isolated problems but a complex system of pressures that feed into one another, creating a fragile ecosystem on the brink of shattering.

| Category of Challenge | Specific Challenge | Impact on Industry |

| Economic | Rising Input Costs | Fuel (natural gas) and raw materials (soda ash) are significantly more expensive than in competitor nations like China, reducing profit margins and global competitiveness.21 |

| Stiff International Competition | Cheaper, machine-made glass products from China and Europe are capturing market share, especially in decorative items like chandeliers.9 | |

| Shifting Consumer Tastes | A cultural shift away from glass bangles towards metal jewellery has caused a significant dip in demand for the industry’s traditional core product.8 | |

| Global Market Volatility | Reliance on exports makes the industry highly vulnerable to international tariffs (e.g., US tariffs) and geopolitical instability (e.g., Sri Lankan economic crisis).20 | |

| Environmental | Taj Trapezium Zone (TTZ) Regulations | The Supreme Court-mandated switch from coal to cleaner but more expensive natural gas to protect the Taj Mahal made many smaller, traditional units economically unviable.21 |

| Severe Air Pollution | Despite the fuel switch, Firozabad’s air quality remains poor, with PM10 and PM2.5 levels consistently exceeding safe limits. The glass industry is a major contributor (20-40%).38 | |

| Climate Change | Rising global temperatures have exacerbated the extreme heat inside workshops, leading to a public health crisis among workers and threatening productivity.30 | |

| Social | Labor Exploitation | The industry is plagued by low wages, lack of social security, poor safety standards, and the continued, though often hidden, use of child labour.3 |

| Vulnerability of Women Workers | Women in the unorganised, home-based sector face the most extreme exploitation, with no legal protection or bargaining power.31 | |

| Technological | Technological Stagnation | Many units continue to use primitive, inefficient technology for melting, shaping, and design, hindering innovation and productivity.23 |

| Infrastructure Deficits | Poor roads, erratic power supply, and bureaucratic delays in export processes create operational bottlenecks and reduce overall efficiency.37 |

The environmental regulations designed to protect a national treasure, the Taj Mahal, had the unintended consequence of pushing many small, family-run bangle furnaces out of business due to the high cost of natural gas.21 This regulatory pressure, combined with changing fashion trends, accelerated the industry’s pivot towards less artistic but more profitable mass-produced goods like bottles. Meanwhile, even with the mandated use of cleaner fuel, the sheer concentration of industry, coupled with other sources like garbage burning and road dust, means Firozabad continues to choke on polluted air.38 The lack of investment in modern, efficient technology makes it difficult to compete with global players like China on price, while the deeply entrenched system of labour exploitation undermines the industry’s social sustainability and the well-being of its people.37 Each challenge is a crack in the glass, and together they threaten to shatter the entire structure.

The Path Forward: Innovation, Adaptation, and Survival

Navigating this complex web of challenges requires a radical reimagining of Firozabad’s future. The path forward is not a single road but a convergence of innovation, adaptation, and a renewed commitment to the industry’s human core.

A pivotal role in this transformation falls to institutions like the Centre for the Development of Glass Industry (CDGI). Established as a joint venture between the Indian government and UN development programs, CDGI’s mandate is to be a catalyst for change, providing crucial support in technology upgradation, energy conservation, skill development, and pollution control.42 Its success in designing more fuel-efficient furnaces, developing longer-lasting melting pots, and providing training on modern techniques is essential for the survival of small and medium-sized enterprises.42 The industry’s future may well depend on its ability to fully leverage the expertise and resources that CDGI offers.

The technological imperative is undeniable. To remain competitive, the industry must move beyond its pockets of primitive technology. This means investing in modern, energy-efficient furnaces, exploring new glass compositions that melt at lower temperatures, and adopting automation for standardised products to compete with mass manufacturers.23 However, innovation must also focus on enhancing the value of its unique crafts. This involves creating new designs that appeal to contemporary global tastes and using technology not to replace artisans, but to empower them with better tools and processes.23

Diversification and value addition are key strategies for economic resilience. The shift to a wider product range is already underway, but the future lies in moving up the value chain. Instead of competing on price with mass-produced Chinese goods, Firozabad can leverage its unique heritage. By marketing its products as authentic, handcrafted works of art made from recycled materials, it can appeal to a growing global market of conscious consumers.22 Collaborations with international designers and brands, such as the one with Creative Women, demonstrate a viable model where traditional skills are applied to create premium, high-value products for export, ensuring fair wages for artisans.22

Ultimately, no economic or technological solution can be sustainable without addressing the human element. The industry’s long-term survival is impossible if it continues to be built on a foundation of exploitation. This requires a seismic shift towards ethical labor practices: strict enforcement of labor laws, ensuring fair and minimum wages, providing social security and health benefits, and making a non-negotiable commitment to improving workplace safety. Eliminating child labor and empowering the industry’s vast and vulnerable female workforce are not just moral imperatives; they are economic necessities for building a stable and resilient future.31

This leads to the most profound question for Firozabad’s future: what will become of its “craft consciousness”? Can the centuries-old, hereditary skills of the Kanchhkars find a new, respected, and economically viable place in a modernised industry? Or are they destined to fade away, replaced by machines and mass production, becoming a quaint relic of a bygone era? The answer to this question will determine not just the future of an industry, but the very soul of the City of Glass.

Conclusion

Firozabad is a city of brilliant, beautiful contradictions. It is where discarded waste is transformed into objects of desire, and where immense heat and hardship are the crucibles for delicate art. The glimmer of a finished bangle and the grit of the factory floor are not separate realities; they are two sides of the same coin, inextricably linked in a cycle of creation and cost. The story of Firozabad is a microcosm of the challenges facing traditional craft industries in a rapidly globalising world: the struggle to preserve heritage while ensuring economic viability, the tension between manual skill and industrial automation, and the urgent need to balance profit with human dignity and environmental health.

The future of the City of Glass depends on its ability to forge a new identity—one that does not abandon its past but builds upon it. It must be an identity that honours the profound skill of its artisans while embracing the technological and ethical standards of the 21st century. It requires a collective will—from factory owners, government bodies, exporters, and consumers—to invest not just in better furnaces and new designs, but in the people who are the living heart of this craft. The shimmering, timeless beauty of Firozabad’s glass can only be truly sustainable if the hands that shape it are protected, the air they breathe is clean, and the legacy they carry forward is treated not as a cheap commodity, but as the precious heritage it is.

Disclaimer

This article is a comprehensive report based on research from publicly available academic papers, news articles, and institutional reports published up to early 2025. The socio-economic, environmental, and market conditions within the Firozabad glass industry are dynamic and subject to change. The views and statistics presented reflect the information available at the time of writing.

Reference

- History of Firozabad, British Rule in Firozabad, Modern History, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.firozabadonline.in/guide/history-of-firozabad

- Experience the centuries-old glass making tradition of Firozabad in UP – The Times of India, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/travel/destinations/experience-the-centuries-old-glass-making-tradition-of-firozabad-in-up/articleshow/100850078.cms

- Beautiful Glass Bangles From Bangle City Firozabad- A Guide, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://thesareeblog.com/beautiful-glass-bangles-from-bangle-city-firozabad-a-guide/

- The Glass Experiment- Shards of Firozabad. – ‘Arch’-type., accessed on September 1, 2025, http://niveditaagupta.blogspot.com/2013/06/the-glass-experiment-shards-of-firozabad.html

- field visit report on bangle factory, firozabad, uttar pradesh, india – ProSPER.Net, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://prospernet.ias.unu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Bangle-Factory_field-trip-report.pdf

- Firozabad’s famous glass bangle industry continues to attract infamy for poor working conditions – Down To Earth, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.downtoearth.org.in/pollution/firozabads-famous-glass-bangle-industry-continues-to-attract-infamy-for-poor-working-conditions

- Firozabad: Where India’s Glass Art Thrives – All About UP, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.allaboutup.com/districts-of-up/all-about-firozabad/

- All About The Glass Bangle Craft Of Firozabad, Which Is Slowly …, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.outlooktraveller.com/celebrating-people/all-about-the-glass-bangle-craft-of-firozabad-that-is-slowly-losing-its-sheen

- Firozabad: The Glass City – Ayra, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://ayra.social/core/article/firozabad-the-glass-city-767dec10-a7e0-4f3d-a2d4-bc4d62383ab9-en

- www.incredibleindia.gov.in, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.incredibleindia.gov.in/en/uttar-pradesh/firozabad-glass#:~:text=The%20History%20of%20Firozabad%20Glass,that%20the%20industry%20started%20flourishing.

- firozabad.nic.in, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://firozabad.nic.in/economy/#:~:text=Glass%20Manufacturing%20Sector%20in%20Firozabad&text=In%20olden%20days%2C%20invaders%20brought,the%20glass%20industry%20in%20Firozabad.

- Firozabad – The Glass City of India, Uttar Pradesh, India. – YouTube, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QT6l7_1061A

- OF GLASS, SKILLS AND LIFE: CRAFT … – CSH Delhi, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.csh-delhi.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/KABA-Firozabad_WP18_FINAL.pdf

- BLOG :: Firozabad Glass Industry – Anuna, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://anuna.com/blog/firozabad-glass-industry/

- Glass industry of Firozabad Uttar Pradesh: traditional craft to, accessed on September 1, 2025, http://dspace.spab.ac.in/xmlui/handle/123456789/2066

- Health and Environmental Impacts of Glass Industry (A Case Study of Firozabad Glass Industry) – EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH, VOL, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://euacademic.org/UploadArticle/1065.pdf

- D’source Making Process | Glass Bangles – Firozabad | D’Source …, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.dsource.in/resource/glass-bangles-firozabad/making-process

- Firozabad glass cluster (Uttar Pradesh) – SAMEEEKSHA, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://sameeeksha.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=133&Itemid=502

- Firozabad Glass Craft | ExcellentCraftsmenship – GiTAGGED, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.gitagged.com/online-store/handicraft/natural-craft/firozabad-glass-craft/

- timesofindia.indiatimes.com, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/agra/lanka-crisis-uttar-pradeshs-firozabad-glass-industry-awaiting-rs-5-crore-payment-exports-on-hold/articleshow/92928856.cms#:~:text=The%20Firozabad%20glass%20industry%20has,imports%20stood%20at%20%241%20billion.

- Dip in demand for its famed glass bangles sees Firozabad embrace all glassware – Invest UP, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://invest.up.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Dip-demand_290424.pdf

- Glass Blowers of Firozabad – Creative Women, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://creativewomen.net/pages/artisan/glass-blowers-of-firozabad

- Status Update – DCMSME, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.dcmsme.gov.in/tcsp/Program%20Overview/Firozabad_V1.pdf

- Glassware Products,Melamine Dinner Set,Ceramic Ware Exporters Uttar Pradesh, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.stbalajiglass.com/

- advocating for the development of the nigerian indigenous glass industry following after the firozabad paradigm – ResearchGate, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322958855_ADVOCATING_FOR_THE_DEVELOPMENT_OF_THE_NIGERIAN_INDIGENOUS_GLASS_INDUSTRY_FOLLOWING_AFTER_THE_FIROZABAD_PARADIGM

- After tariff hike, future tense for Firozabad glass industry – Hindustan Times, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/lucknow-news/after-tariff-hike-future-tense-for-firozabad-glass-industry-101756580773645.html

- US tariffs cause serious concern among Firozabad glass exporters – The Statesman, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.thestatesman.com/india/us-tariffs-cause-serious-concern-among-firozabad-glass-exporters-1503468390.html

- Glass: Lanka crisis: Uttar Pradesh’s Firozabad glass industry …, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/agra/lanka-crisis-uttar-pradeshs-firozabad-glass-industry-awaiting-rs-5-crore-payment-exports-on-hold/articleshow/92928856.cms

- Glass bangle industry faces new adversary – climate change – The Times of India, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/environment/glass-bangle-industry-faces-new-adversary-climate-change/articleshow/111110973.cms

- Glass bangle industry faces new adversary – climate change – The Economic Times, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://m.economictimes.com/industry/indl-goods/svs/paper-/-wood-/-glass/-plastic/-marbles/glass-bangle-industry-faces-new-adversary-climate-change/articleshow/111106526.cms

- Breaking the Silence: The Plight of Women Workers in the … – IJNRD, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://ijnrd.org/papers/IJNRD2503443.pdf

- A Study on adverse effect of smoke/flue on lung functions of glass factory workers of Firozabad district – ResearchGate, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286516746_A_Study_on_adverse_effect_of_smokeflue_on_lung_functions_of_glass_factory_workers_of_Firozabad_district

- Ocular Surface in Bangle Makers of Firozabad – International Journal of Research and Review, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.ijrrjournal.com/IJRR_Vol.11_Issue.6_June2024/IJRR35.pdf

- Socio-Economic-Status-of-Women-Labour-in-Bangle-Industry-A-Case-Study-of-Firozabad-City-India.pdf – ResearchGate, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Syed-Kausar-Shamim/publication/355666653_Socio-Economic_Status_of_Women_Labour_in_Bangle_Industry_A_Case_Study_of_Firozabad_City_India/links/6178ed360be8ec17a9355d8b/Socio-Economic-Status-of-Women-Labour-in-Bangle-Industry-A-Case-Study-of-Firozabad-City-India.pdf

- Working Environment and Health Challenges of Women … – IJFMR, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.ijfmr.com/papers/2025/2/40592.pdf

- Of glass, skills and life: trade consciousness among Firozabad’s glass workers – ResearchGate, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/370165415_Of_glass_skills_and_life_trade_consciousness_among_Firozabad’s_glass_workers

- A STUDY OF FIROZABAD BANGLE INDUSTRY – IJAPRR: International Journal of Allied, Practice Research and Review, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.ijaprr.com/download/1440312106.pdf

- Taj Mahal not affected by glass industry pollution: environmental …, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.glassonline.com/taj-mahal-not-affected-by-glass-industry-pollution-environmental-report/

- ACTION PLAN FOR THE CONTROL OF AIR POLLUTION IN FIROZABAD REGIONAL OFFICE HOUSE NO. 77, GALI NO. 2, MAHAVIR NAGAR FIROZABAD, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://cpcb.nic.in/Actionplan/Firozabad.pdf

- THE ‘BROKEN’ BANGLE INDUSTRY – Jus Corpus, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.juscorpus.com/the-broken-bangle-industry/

- INTERNATIONAL – The All India Glass Manufacturers’ Federation, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.aigmf.com/International-Seminar-Firozabad.pdf

- MSME-Technology – DCMSME, accessed on September 1, 2025, https://dcmsme.gov.in/old/MSME-DO/ktdgi01x.htm

- Welcome to Centre for the Development of Glass Industry (CDGI), accessed on September 1, 2025, https://www.cdgiindia.net/