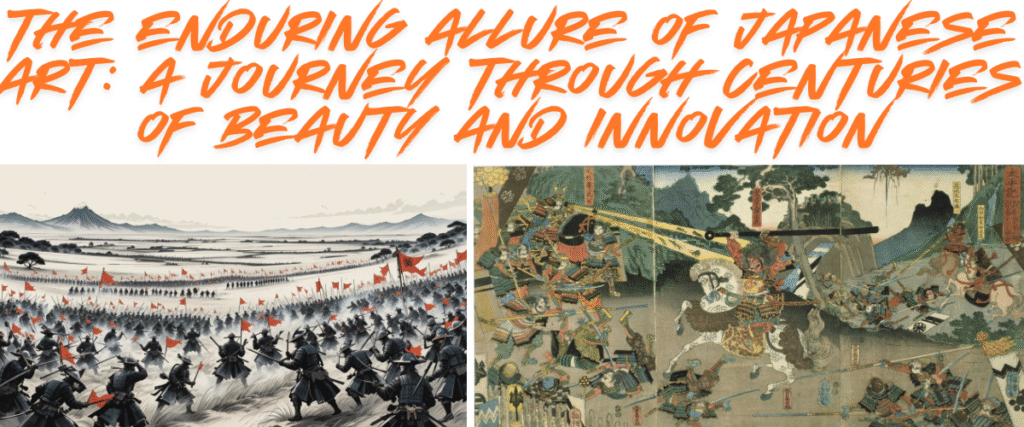

From serene landscapes to vibrant woodblock prints and from intricate ceramics to powerful samurai armour, Japanese art possesses a unique, captivating quality that has enchanted the world for centuries. It’s evidence of a culture deeply rooted in aesthetics, where beauty isn’t just an embellishment but an integral part of life itself. Join us on a journey through the fascinating world of Japanese art, where we explore its rich history, diverse forms, and enduring influence.

A Glimpse into Japan’s Artistic Soul: What Makes Japanese Art So Special?

Before we delve into specific periods and forms, let’s consider what sets Japanese art apart. At its heart, Japanese art often embodies several core principles:

- Harmony with Nature: Nature is a constant muse in Japanese art, not just as a backdrop but as a central theme. Mountains, rivers, cherry blossoms, and the changing seasons are depicted with reverence and an understanding of their fleeting beauty. This connection often stems from Shinto beliefs, which emphasise the sacred nature of the natural world.

- Wabi-Sabi: The Beauty of Imperfection and Transience: This profound aesthetic concept finds beauty in the imperfect, the impermanent, and the incomplete. It accepts the natural cycle of development, deterioration, and aging. Think of a rustic tea bowl with an irregular glaze or a weathered stone lantern – these embody wabi-sabi. It’s about finding profound beauty in simplicity and authenticity rather than striving for flawless perfection.

- Ma: The Power of Empty Space: “Ma” refers to the deliberate use of empty or negative space in a composition. It’s not just about what’s there but also about what isn’t. This concept allows for contemplation and breathing room, often amplifying the impact of the elements that are present. It’s a fundamental principle in everything from painting to architecture.

- Attention to Detail and Craftsmanship: Japanese artisans are renowned for their meticulous attention to detail and extraordinary craftsmanship. Whether it’s the precise brushstrokes of a painting, the intricate joinery of a wooden temple, or the delicate patterning on a kimono, the dedication to perfection in execution is evident in every piece.

- Storytelling and Symbolism: Many forms of Japanese art are imbued with rich layers of symbolism and narrative. From mythical creatures and legendary heroes to everyday life and historical events, art often serves as a visual language to convey stories, morals, and cultural values.

- Adaptation and Innovation: While deeply rooted in tradition, Japanese art has also shown a remarkable capacity for adaptation and innovation. It has absorbed influences from other cultures, particularly China and Korea, but has always transformed them into something uniquely Japanese, evolving and creating new styles throughout its history.

These principles, woven into the fabric of Japanese artistic expression, give it its distinctive character and universal appeal.

Prehistoric and Ancient Eras: The Genesis of Japanese Art (c. 10,000 BCE – 794 CE)

Our journey begins in the mists of time, where the earliest traces of Japanese art emerge:

- Jōmon Period (c. 10,000 – 300 BCE): This prehistoric period is famous for its distinctive Jōmon pottery. These earthenware vessels, often intricately decorated with rope patterns (the word “Jōmon” literally means “rope-patterned”), are some of the oldest in the world. They range from simple, functional pieces to elaborate, flame-like vessels, demonstrating a remarkable artistic sensibility. Dogū, small clay figurines often characterised by their abstract and stylised forms, also hail from this era, likely serving ritualistic purposes.

- Yayoi Period (c. 300 BCE – 300 CE): The Yayoi period saw the introduction of agriculture, metalworking (bronze and iron), and new pottery styles from the Asian mainland. While less ornate than Jōmon pottery, Yayoi ware was more practical. Dotaku (bronze bells), often adorned with patterns of animals or daily life, are characteristic artifacts believed to have been used in agricultural rituals.

- Kofun Period (c. 300 – 710 CE): Named after the massive burial mounds (“kofun”) built for the ruling elite, this period is notable for its haniwa figurines. These unglazed clay figures, ranging from simple cylinders to detailed representations of people, animals, and houses, were placed around the kofun, likely serving as guardians or spiritual companions for the deceased.

- Asuka Period (538 – 710 CE) and Nara Period (710 – 794 CE): The arrival of Buddhism from Korea in the mid-6th century marked a profound shift in Japanese art. Buddhist temples, sculptures, and paintings became central to the culture.

- Asuka Period: This era witnessed the construction of magnificent temples, such as Hōryū-ji, which housed stunning Buddhist sculptures often characterised by their serene expressions and flowing drapery, strongly influenced by Chinese and Korean Buddhist art. The Tamamushi Shrine at Hōryū-ji is a prime example of exquisite craftsmanship from this period, featuring lacquered panels depicting Buddhist stories.

- Nara Period: The Nara period, with Nara as the first permanent capital, witnessed a flourishing of Buddhist art on an even grander scale. The Tōdai-ji Temple, with its colossal bronze statue of the Great Buddha (Daibutsu), is a testament to the period’s ambition. Many of the sculptures from this era, particularly those in the “Tenpyō” style, display a more lifelike and robust quality.

Classical Eras: The Golden Age of Refinement (794 – 1573 CE)

These periods saw the development of distinctly Japanese artistic styles, moving away from direct continental influences:

- Heian period (794 – 1185 CE): With the capital moved to Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto), a highly refined court culture blossomed, giving rise to unique Japanese aesthetics.

- Esoteric Buddhist Art: During the Early Heian period, the rise of Esoteric Buddhism (Shingon and Tendai sects) was evident, characterised by complex mandalas and wrathful deities. Art from this period, often characterised by vibrant colours and powerful forms, served as aids for meditation and ritual.

- Yamato-e (Japanese-style Painting): This was a pivotal development. Yamato-e broke from Chinese landscape traditions, focusing on Japanese subjects – landscapes, literary narratives, and daily life – often depicted with vibrant colours and distinctive compositional techniques like “blown-off roofs” (fukinuki yatai) to reveal interior scenes. The Genji Monogatari Emaki (Illustrated Handscrolls of The Tale of Genji) is the quintessential example of Yamato-e, offering a glimpse into the courtly life and emotions of the time. Calligraphy also became an art form in its own right, often combined with poetry and painting.

- Kamakura Period (1185–1333 CE): A period of samurai rule, this era witnessed a shift towards a more realistic and dynamic artistic expression, reflecting the warrior ethos.

- Sculpture: Buddhist sculpture evolved to become more lifelike, sometimes even grimly realistic, portraying individual features and emotions. Unkei and Kaikei are renowned sculptors whose works exemplify this powerful, dynamic style. The colossal guardian figures (Niō) at Tōdai-ji are iconic examples.

- Portraiture: Realistic portraiture, particularly of Buddhist monks and samurai leaders, also gained prominence.

- Emaki: While still popular, emaki scrolls began to depict more dramatic events, battles, and narratives of popular legends.

- Muromachi Period (1333–1573 CE): This period witnessed the rise of Zen Buddhism, which had a profound influence on various art forms, promoting simplicity, introspection, and a connection with nature.

- Ink Painting (Sumi-e): Zen Buddhist monks introduced Chinese-style ink painting (sumi-e) to Japan, which flourished. Artists like Sesshū Tōyō became masters of this monochromatic style, using varying shades of ink to create evocative landscapes, often characterised by bold brushstrokes and an emphasis on empty space. Sumi-e perfectly embodied Zen principles of spontaneity and enlightenment.

- Tea Ceremony (Chanoyu) and Related Arts: The elaborate tea ceremony, deeply intertwined with Zen philosophy, underwent significant refinement during this period. It led to the development of specific aesthetics for tea bowls (chawan), flower arrangements (ikebana), and garden design, all emphasising simplicity, naturalness, and a sense of tranquil beauty.

- Noh Theatre: The highly stylised and symbolic Noh theatre also developed during this period, incorporating masked performances, poetic recitations, and subtle movements to create a unique blend of drama and spiritual contemplation.

Early Modern and Edo Period: Art for the Masses and the Rise of Ukiyo-e (1573 – 1868 CE)

The unification of Japan under powerful shoguns brought stability and the rise of a thriving urban merchant class, leading to new artistic expressions:

- Momoyama Period (1573 – 1603 CE): A short but impactful period characterised by grandeur, dynamism, and opulence, reflecting the power of the warlords like Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

- Castle Architecture and Screen Painting: Magnificent castles designed for defence and display were built. Their interiors were often adorned with opulent screen paintings (byōbu) and sliding door panels (fusuma), depicting bold landscapes, genre scenes, and mythical creatures in vibrant colours, often using gold leaf to reflect light and symbolise wealth. Artists like Kanō Eitoku were masters of this grand style.

- Lacquerware: Elaborate lacquerware, often inlaid with mother-of-pearl or gold (maki-e), also became highly prized.

- Edo Period (1603–1868 CE): With the capital relocated to Edo (modern Tokyo), a prolonged period of peace and prosperity ensued, fostering a vibrant urban culture and diverse artistic movements. It is arguably one of the most recognisable periods in Japanese art.

- Ukiyo-e (Pictures of the Floating World): This is perhaps the most famous and influential art form of the Edo period. Ukiyo-e woodblock prints depicted the transient pleasures and everyday life of the urban commoners: kabuki actors, beautiful courtesans, sumo wrestlers, popular landscapes, and scenes from daily life.

- Early Masters: Artists like Hishikawa Moronobu laid the groundwork for Ukiyo-e.

- The Golden Age of Ukiyo-e: The 18th and 19th centuries marked the peak of Ukiyo-e. Kitagawa Utamaro excelled in portraits of beautiful women, capturing their elegance and inner thoughts. Tōshūsai Sharaku produced enigmatic and powerful portraits of kabuki actors.

- Landscape Masters: Katsushika Hokusai (with his iconic “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” from the “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” series) and Andō Hiroshige (known for his “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” series) revolutionised landscape prints, inspiring Western Impressionists. Their ability to capture atmosphere, movement, and the beauty of ordinary scenes is unparalleled.

- Rinpa School: This indigenous decorative style, revitalised by artists like Ogata Kōrin, focused on bold, colourful designs, often with metallic backgrounds, depicting natural themes such as flowers, birds, and waves. Its elegant simplicity and decorative flair characterise it.

- Nanga (Literati Painting): Influenced by Chinese literati painting, Nanga artists emphasised personal expression and scholarly pursuits, often depicting landscapes in a more understated and subtle manner.

- Ceramics: The Edo period also witnessed a continued flourishing of regional ceramic traditions, including Arita ware (also known as Imari ware), Kutani ware, and Satsuma ware, which produced exquisite porcelain and earthenware for both domestic and export markets.

- Netsuke and Inrō: These miniature carvings (netsuke, used as toggles for kimonos) and segmented containers (inrō, for carrying small items) became highly refined art forms, showcasing incredible detail and craftsmanship.

- Ukiyo-e (Pictures of the Floating World): This is perhaps the most famous and influential art form of the Edo period. Ukiyo-e woodblock prints depicted the transient pleasures and everyday life of the urban commoners: kabuki actors, beautiful courtesans, sumo wrestlers, popular landscapes, and scenes from daily life.

Modern and Contemporary Japanese Art: Global Connections and New Expressions (1868 CE – Present)

The Meiji Restoration in 1868 opened Japan to the West, ushering in a period of rapid modernisation and profound artistic transformation:

- Meiji Period (1868 – 1912 CE): The initial Westernisation led to a decline in traditional arts like Ukiyo-e as oil painting and Western techniques gained popularity. However, there was also a movement to preserve and revive traditional Japanese arts. Artists experimented with blending Western techniques with Japanese aesthetics. Yokoyama Taikan was a prominent artist who spearheaded the nihonga (Japanese painting) movement, seeking a modern expression while rooted in traditional styles.

- Taishō (1912 – 1926 CE) and Early Shōwa Periods (1926 – 1989 CE): This era saw the emergence of new art movements, including Japanese Surrealism and Expressionism, as artists engaged with international trends. The Sōsaku Hanga (creative prints) movement saw artists taking full control of the printmaking process, from design to carving and printing, in contrast to the collaborative Ukiyo-e system.

- Post-War and Contemporary Art (1945–Present): Following World War II, Japanese art underwent significant transformations, reflecting a more globalised perspective and addressing pressing social and political issues.

- Gutai Art Association: Formed in the 1950s, this radical avant-garde group pushed the boundaries of art, emphasising performance, process, and the interaction between art and the body. Their motto, “Do not imitate others, but try to create something new,” epitomised their experimental spirit.

- Mono-ha (School of Things): Active in the late 1960s and early 1970s, this movement focused on the relationships between natural and industrial materials, often creating minimalist installations that explored the inherent properties of objects and their interaction with space.

- Superflat: Coined by artist Takashi Murakami, Superflat is a postmodern art movement that critiques and blends elements of traditional Japanese art, manga, and anime, exploring consumerism and pop culture. Murakami himself is a global art superstar, blurring the lines between fine art, commercial art, and merchandise.

- Contemporary Trends: Today, Japanese art is incredibly diverse, encompassing a wide range of styles, from installation art, video art, and digital art to performance art and street art. Artists such as Yayoi Kusama (known for her polka dots and infinity rooms), Yoshitomo Nara (with his distinctive childlike figures), and Ryoji Ikeda (who explores data and soundscapes) have gained international acclaim, demonstrating the continued vitality and innovation of Japanese artistic expression on the global stage.

The Enduring Legacy and Global Impact

Japanese art has not only shaped its own culture but has also had a profound impact on the global art scene. The influence of Ukiyo-e on European Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, particularly on artists such as Van Gogh, Monet, and Degas, is well-documented and widely recognised. Japanese aesthetics, such as wabi-sabi and the concept of “ma,” have permeated Western design, architecture, and even philosophy.

From the meticulous craftsmanship of ancient pottery to the bold expressions of contemporary artists, Japanese art continues to evolve, reflecting the ongoing dialogue between tradition and modernity, nature and urbanity, and individual expression and collective identity. It reminds us that art is not just about visual appeal but about deeper cultural values, spiritual beliefs, and a unique way of seeing the world.

Conclusion

Our journey through Japanese art reveals a continuous thread of aesthetic appreciation, innovation, and a deep connection to nature and spiritual well-being. From the ancient Jōmon pottery to the global phenomenon of contemporary art, every era has added to the diverse range of artistic expression. The enduring appeal of Japanese art lies in its ability to balance profound philosophy with exquisite craftsmanship, creating works that resonate deeply with viewers across cultures and generations. It’s a powerful reminder of humanity’s boundless creativity and our innate desire to find and create beauty in the world around us.

Disclaimer

The information presented in this blog post is intended for general informational purposes only and serves as an introductory overview of Japanese art. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy and provide a comprehensive summary, the vast and intricate nature of Japanese art history means that this blog cannot cover every detail, artist, or movement. Readers are encouraged to consult further specialised resources and academic texts for in-depth study. Artistic periods and classifications overlap or are subject to different scholarly interpretations. This blog aims to spark interest and appreciation for the magnificent world of Japanese art.