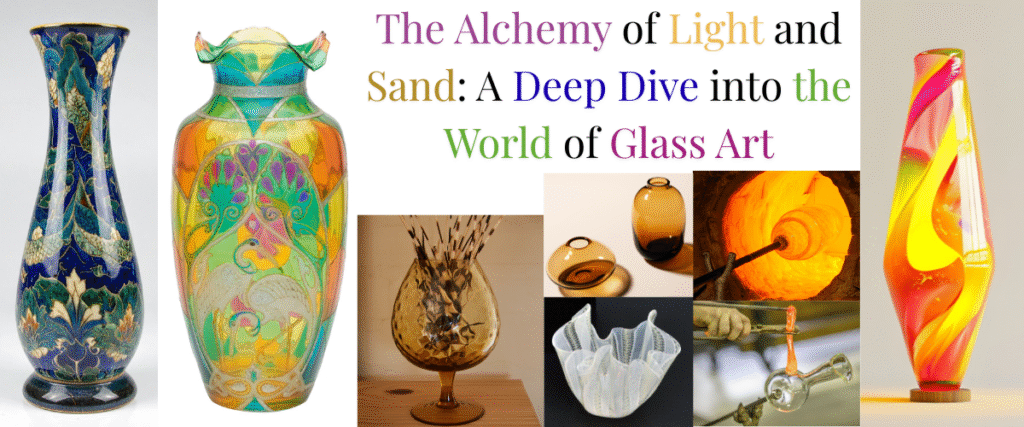

Step into a gallery showcasing glass art, and you’re entering a world of frozen light. A sculpture might twist towards the ceiling like a vibrant, solid flame. A bowl might hold the deep, swirling blues of a nebula. A window might not just let in the light but shatter it into a thousand coloured prayers. This is the magic of glass art—an ancient craft that dances on the razor’s edge between solid and liquid, fragility and strength, science and soul.

Glass is a paradoxical material. We think of it as a solid, yet it’s technically an amorphous solid, a liquid that has cooled so rapidly its molecules never had time to align into a crystalline structure. It is born from the humblest of materials—sand (silica), soda ash, and lime—and transformed by the most primal of elements: fire. In the hands of an artist, this molten, honey-like substance becomes a medium for breathtaking expression.

But how does it happen? How does a pile of sand become a delicate perfume bottle or a monumental installation? Join us as we journey through the furnace, exploring the history, techniques, and brilliant minds behind this mesmerising art form.

A Brief, Sparkling History: From Ancient Beads to Modern Masterpieces

The story of glass art is as rich and layered as the material itself. It’s a tale of discovery, secret formulas, and revolutionary ideas that stretches back millennia.

The Dawn of Glass: Ancient Origins

Our adventure started more than 4,000 years ago in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt. The earliest glass wasn’t clear; it was an opaque, precious material, often blue or green, treasured like gemstones. Craftsmen would create small objects like beads, amulets, and inlays by wrapping molten glass around a core of clay and dung. Once cooled, the core was painstakingly scraped out, leaving a small, hollow vessel. These were luxury items, symbols of wealth and power reserved for pharaohs and priests.

The Roman Revolution: The Invention of Glassblowing

The single most important innovation in glass history occurred around 50 BCE, likely in the Syro-Palestinian region. A clever artisan discovered that a blob of molten glass could be gathered on the end of a hollow pipe and inflated with a puff of breath. This was the invention of glassblowing, and it changed everything.

The Romans, Masters of Engineering and dissemination, quickly adopted and perfected this technique. Suddenly, glass could be made faster, thinner, and in a far greater variety of shapes. It transformed from a rare luxury to a common household item. Windows, cups, bottles, and jugs became accessible to more people. The Romans were also pioneers in creating mosaics and decorative panels, laying the groundwork for future artistic endeavours.

The Gothic Glow: Stained Glass and Sacred Light

Following the collapse of the Roman Empire, glassmaking methods in Europe fragmented. However, one form of glass art rose to glorious prominence during the Middle Ages: stained glass. As magnificent Gothic cathedrals reached for the heavens, their walls were filled with vast, intricate windows. These weren’t just decorations; they were “Biblia Pauperum” or the “Bible of the Poor.” They told biblical stories in radiant colour to a largely illiterate populace. Artisans would create coloured glass by adding metallic oxides to the molten mix—cobalt for blue, manganese for purple, and gold for a rich ruby red. The pieces were then cut to shape, painted with details, and joined with lead came. Standing in a cathedral like Chartres in France, bathed in the ethereal light filtering through these medieval masterpieces, is a truly spiritual experience.

The Venetian Monopoly: The Secrets of Murano

During the Renaissance, the epicentre of artistic glassmaking moved to Venice. The Venetian glassmakers were so skilled, and their techniques so valuable, that in 1291 the entire industry was moved to the nearby island of Murano. This was partly to protect the wooden city of Venice from the risk of fire from the furnaces, but it was also to guard their coveted secrets. Murano glassblowers developed techniques for creating cristallo, a supremely clear glass that mimicked rock crystal, as well as intricate methods like millefiori (a thousand flowers) and latticino (filigree patterns). For centuries, Murano dominated the world of luxury glass.

The Studio Glass Movement: Art Breaks Free

For most of its history, glass art was the product of factories and teams of craftsmen. The idea of a solo artist working with glass in their own studio was unthinkable due to the massive, industrial-scale equipment required. This all changed in the 1960s.

In 1962, a ceramics professor named Harvey Littleton, with the help of scientist Dominick Labino, held two workshops at the Toledo Museum of Art. They developed a small, affordable furnace and a new glass formula that melted at a lower temperature. For the first time, it was possible for an individual artist to melt, blow, and shape glass in a private studio. The American Studio Glass Movement began around this time, a revolution that spread worldwide. It untethered glass from its functional, factory-based past and elevated it to a medium for personal, sculptural expression, just like painting or sculpture.

The Alchemist’s Toolkit: Techniques of the Glass Artist

Glass is not a single medium; it’s a universe of possibilities. Artists can work with it hot, warm, or cold, and each temperature range offers a unique set of techniques.

Hot Glass: The Dance with Fire

This is what most people picture when they think of glass art—the dramatic, fiery process of working with glass in its molten state, typically above 1000°C (around 1900°F).

- Glassblowing: The quintessential technique. The artist, or gaffer, uses a long, hollow steel blowpipe to gather a “gob” of molten glass from a furnace. They then roll it on a steel table (a marver) to shape it, periodically reheating it in a secondary furnace called the glory hole. By blowing air through the pipe, they inflate the glass, much like a bubble. With a combination of tools like jacks, shears, and tweezers, along with the forces of gravity and centrifugal motion, they shape the vessel. It’s a fast-paced, fluid dance that requires immense skill, timing, and often a team of assistants.

- Hot Sculpting: This is similar to glassblowing but without the blowing. The artist gathers solid masses of molten glass and shapes them using handheld tools and benches. This technique is used to create solid sculptures, from abstract forms to realistic figures.

- Lampworking (or Flameworking): A more intimate and precise technique. Instead of a large furnace, the artist uses a bench-mounted torch that burns a mixture of gas and oxygen to melt pre-made rods and tubes of glass. This is the method used to create intricate beads, delicate figurines, scientific glassware, and complex sculptures like marbles. Borosilicate glass (like Pyrex), with its high thermal shock resistance, is often the glass of choice for lampworkers.

Warm Glass: The Patience of the Kiln

Warm glass techniques happen in a kiln at temperatures that make the glass soft and plastic, typically between 650°C and 900°C (1200°F – 1650°F). It’s a slower, more controlled process than hot glass work.

- Fusing: This is the process of stacking pieces of coloured sheet glass together and heating them in a kiln till they melt and fuse into a single, seamless piece. The key to successful fusing is using glasses that are compatible, meaning they have the same Coefficient of Expansion (COE). If incompatible glasses are fused, they will crack and shatter as they cool at different rates. Artists can create incredibly detailed, painterly effects by fusing.

- Slumping and Draping: These techniques are often used after fusing. A flat, fused piece of glass is placed over a ceramic or steel mould and heated in the kiln again. As the glass softens, gravity pulls it down into or over the mould, taking its shape. This is how glass plates, bowls, and undulating sculptural forms are made. Draping is similar, but the glass melts over the top of a form, like a steel post, creating a flowing, fabric-like shape.

- Kiln Casting: This involves melting chunks or crushed glass (called frit) inside a refractory mould in a kiln. The artist first creates a model (often from clay or wax) and then builds a durable mould around it. The model is removed, and the mould is filled with glass and fired. The glass melts and flows to fill the entire cavity, creating a solid, dense glass object. This process can capture incredible detail and is used to create large-scale sculptural works.

Cold Working: The Final Touch

Cold working refers to any technique performed on glass at room temperature. It’s often the final, finishing stage, but it can also be the primary artistic method.

- Stained Glass: The classic cold working technique. The artist cuts coloured glass to a specific pattern and then joins the pieces together. In traditional stained glass, the pieces are held in channels of lead came, which is then soldered at the joints. In the “Tiffany” method, developed by Louis Comfort Tiffany for his famous lamps, each piece of glass has copper foil wrapped around its edge, and the foiled pieces are then soldered together, allowing for more intricate and three-dimensional designs.

- Etching and Engraving: These are subtractive processes used to create designs on the surface of the glass.

- Sandblasting: A high-pressure stream of abrasive grit (like sand or aluminium oxide) is blasted at the glass through a stencil, carving away the surface and creating a frosted appearance.

- Acid Etching: Hydrofluoric acid is used to corrode the surface of the glass, creating a very fine, satin-like finish. It’s extremely hazardous and requires strict safety protocols.

- Engraving: Using small, diamond-tipped or stone wheels on a lathe, the artist can carve intricate, detailed images directly into the glass surface.

- Grinding and Polishing: These processes use progressively finer grits of abrasive material (like diamond or silicon carbide) to shape, smooth, and polish glass. This is how facets are cut into glass, creating brilliant, gem-like surfaces, and how rough cast pieces are finished to a perfect, clear shine.

Meet the Masters: Icons of Glass Art

Like any art form, the world of studio glass has its legends—artists who pushed the boundaries of the medium and changed our perception of what glass could be.

- Harvey Littleton (1922-2013): Often called the “Father of the Studio Glass Movement,” Littleton was the driving force behind making glass accessible to individual artists. His own work celebrated the fluid, molten nature of glass, creating abstract forms that seemed to capture a moment of movement. His greatest contribution, however, was his tireless work as an educator, inspiring a generation of artists to explore glass.

- Dale Chihuly (b. 1941): Arguably the most famous glass artist in the world. Chihuly is known for his monumental, asymmetrical, and brilliantly coloured installations. He works more like a director than a traditional craftsman, leading a large team of glassblowers to execute his ambitious visions. From his swirling Chandeliers to his Macchia series that explodes with colour, his work is a testament to the spectacular, architectural potential of glass.

- Lino Tagliapietra (b. 1934): A living legend, the Venetian Maestro. Tagliapietra spent decades working in the secretive Murano glass houses before breaking tradition in the 1970s to travel to America and share his unparalleled knowledge with the burgeoning studio glass community. His act of generosity was a crucial bridge between centuries of Venetian technique and the experimental energy of the new movement. His own work is the pinnacle of technical perfection, elegance, and vibrant, complex patterns.

- Clare Belfrage (b. 1966): A leading Australian glass artist, Belfrage draws deep inspiration from the patterns, rhythms, and textures of the natural world. Her blown and sculpted forms are renowned for their intricate surface markings, created by drawing fine lines of coloured glass onto the surface. Her work has a quiet, organic power, evoking images of seed pods, flowing water, and tree bark with a distinctively Australian sensibility.

Starting Your Own Glass Journey: A Word of Caution and Encouragement

Feeling inspired? The allure of glass is powerful, but it’s not a hobby to be taken lightly. Working with glass, especially hot glass, involves extreme temperatures, heavy equipment, and inherent risks.

The best way to start is to seek out professional instruction. Many community art centres and private studios offer beginner workshops in various techniques.

- Lampworking: Often the most accessible entry point. A bead-making class requires less space and equipment and can teach you the fundamentals of how glass behaves in a flame.

- Fusing and Slumping: This is another great starting point. Many studios offer workshops where you can create a small, fused tile or a slumped dish. It’s a fantastic way to learn about colour, design, and the magic of the kiln.

- Glassblowing: The most intensive and expensive option. Look for “taster” sessions or introductory workshops where you can experience the thrill of gathering and shaping molten glass under the close supervision of an experienced instructor.

Collecting glass art is another way to engage with the medium. Start by visiting galleries and student shows. Don’t be afraid to ask questions. A small, beautiful paperweight or a simple fused bowl can be the start of a lifelong passion.

The Future is Clear (and Coloured)

Where is glass art headed? Artists today are pushing the medium in incredible new directions. They are combining glass with other materials like metal and wood, incorporating video and light technology, and using 3D printing to create complex moulds for casting. There is also a growing focus on sustainability, with artists finding ways to reduce energy consumption and recycle glass in their studios.

Glass is no longer just a craft material; it’s a vital and exciting medium for contemporary art, capable of conveying complex ideas and evoking deep emotional responses.

Conclusion: More Than Just a Window

From an ancient Egyptian bead to a sprawling Chihuly installation, glass art is a celebration of transformation. It is a medium that holds light, captures colour, and freezes motion. It demands respect for its scientific properties while offering boundless freedom for artistic expression.

The next time you hold a glass to your lips, look through a window, or admire a colourful vase, take a moment. Think of the fire, the breath, and the skill that went into its creation. You’re holding a piece of an ancient and ongoing story—the story of how we learned to shape light itself.

Disclaimer

This blog post is for informational and educational purposes only. The techniques described, particularly those involving hot glass, kilns, and chemicals, are potentially dangerous and should only be attempted under the supervision and guidance of a qualified professional in a properly equipped studio. The author and publisher of this blog are not liable for any injuries or damages that may result from attempting to replicate these processes. Always prioritise safety, seek professional instruction before working with glass art materials and equipment, and wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).