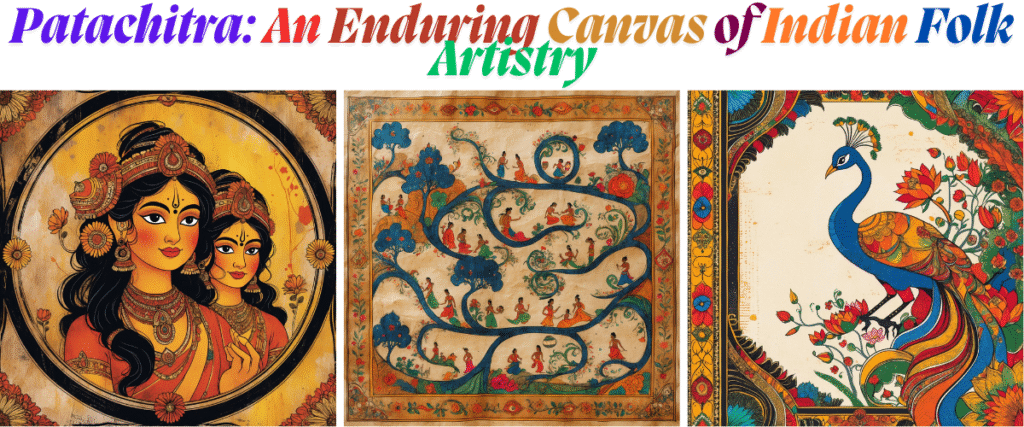

Patachitra, a term derived from the Sanskrit words ‘Patta’ meaning cloth and ‘Chitra’ signifying an image, picture, or painting, represents far more than its literal translation of “cloth-picture”.1 It is a generalised term for a venerable style of cloth-based scroll painting, an art form that transcends mere decoration to become a powerful medium for storytelling.1 This ancient narrative art, particularly vibrant in the eastern Indian states of Odisha and West Bengal, has historically served as a visual accompaniment to sung performances, especially in the Bengali tradition.4

The heritage of Patachitra is exceptionally rich, positioning it as one of India’s most ancient and continuously relevant contemporary art forms.2 Its significance is woven into the cultural fabric of India through its multifaceted roles: as an object of ritual use within temple traditions, as cherished souvenirs for pilgrims seeking tangible connections to sacred sites, and as a dynamic component of narrative performances that disseminated cultural knowledge and religious stories to a wide populace.1 The art form’s geographical heartlands are primarily Odisha and West Bengal, though its influence and practice extend to parts of Bangladesh and Jharkhand.1 A notable cultural interrelation and stylistic similarities exist between the Patachitra traditions of Odisha and Bengal, partly a legacy of historical administrative connections that once bound these regions.18

Patachitra is not a static relic of the past; rather, it functions as a living dialogue between generations, a medium that continually breathes life into ancient myths while simultaneously engaging with modern realities.3 This inherent adaptability is evident from its inception. While the definition “cloth-picture” is straightforward, its varied functions—as a narrative tool, a pilgrim’s memento, and a ritual object—underscore its complex and evolving role in society.1 The art form’s capacity to incorporate contemporary social issues alongside age-old myths demonstrates a continuous conversation with its context, making it far more than a preserved artifact; it is a tradition that actively engages its audience and adapts to changing times.

Furthermore, Patachitra has always navigated a fascinating dual identity, existing comfortably in both sacred and secular spheres. Its origins are deeply embedded in religious ritual, particularly associated with the Jagannath Temple in Puri, where paintings were used when the temple was inaccessible or during the deities’ ritualistic “hibernation”.1 This underscores its profound sacred function. Concurrently, its early commercialisation as “pilgrim souvenirs” introduced a more secular dimension.1 The subsequent evolution to encompass social commentary and even current events further highlights its expansion beyond purely religious narratives into the broader socio-cultural domain.7 This duality is a cornerstone of its enduring resilience and relevance.

Echoes of Antiquity: Tracing the Origins and Historical Journey of Patachitra

The genesis of Patachitra is inextricably linked to sacred traditions and the vibrant culture of pilgrimage in India. Its most profound connection is with the Jagannath Temple in Puri, Odisha, a major spiritual centre.1 Historical accounts suggest that painted representations of the temple deities were utilised for worship during periods when the temple was closed to the public or when the deities themselves were in ‘anasara’ – a ritual period of seclusion or hibernation.1 Beyond its ritualistic use within the temple, Patachitra also flourished as ‘Yatripatis’, or pilgrim souvenirs. These painted cloths served as tangible reminders of a sacred journey and as conduits for continued devotion long after the pilgrim had returned home.1 The development of this art form is largely attributed to the 12th century, coinciding with the construction of the great Jagannath Temple, though some scholars trace its stylistic elements and conceptual roots back to the 5th century BC or even earlier, to prehistoric cave paintings and pottery decorations.2 The Patua tradition of Bengal, while related, claims its own ancient lineage, with some asserting origins in the 10th-11th century CE, during the Pre-Pala period.3

Unravelling the early development of Patachitra reveals stylistic affinities with classical Indian wall murals and the delicate illustrations found in palm leaf manuscripts, suggesting a shared aesthetic heritage.1 Early forms of scroll paintings, such as Charanachitras, Mankhas, and Yamapatas (depicting Yama, the god of death, and the afterlife), were executed on textile scrolls and often dealt with narrative and didactic themes.11 A notable historical reference is found in the writings of Banabhatta in the 7th century AD, which mentions Yam Patas.23

The chronicle of Patachitra is a story of remarkable adaptation and evolution through centuries of historical and cultural shifts. During the flourishing of Buddhism and Jainism in India, Patua artists are believed to have embraced Buddhist themes, with Pata paintings becoming a popular mass medium for disseminating Jataka tales (stories of the Buddha’s previous lives).23 With the resurgence of Hinduism, mythological Patas depicting stories like those of Behula and Chandi gained prominence.23 The advent of Islamic rule saw the emergence of Gaji and Pir Patas, which narrated stories of Muslim saints and warriors, often created by Patua communities in Bengal who themselves were, and often still are, Islamic by faith yet engaged in depicting Hindu narratives as well.3

The colonial period was a time of significant transformation. It witnessed the rise of the distinct Kalighat Pata style in Calcutta (now Kolkata). Initially focusing on mythological figures, Kalighat paintings soon evolved to include satirical depictions of the emerging ‘babu-bibi culture’ (a new anglicised Indian elite) and sharp social commentary on the impacts of colonial rule.3 The decline of the traditional agricultural economy and the rise of new mass media, such as printing presses, posed challenges to Patachitra’s role as a primary source of visual storytelling and entertainment.23 However, this era also saw Patuas creating “songs of awakening” and Patas depicting the Indian freedom struggle, famines, and wars, demonstrating the art form’s continued relevance as a medium of social expression.23 Post-independence, Patachitra has continued to adapt, with artists engaging with contemporary social and political narratives, ensuring its place in the modern cultural landscape.23

The historical journey of Patachitra reveals it as a mirror reflecting India’s profound socio-religious syncretism and transformation. The remarkable shifts in themes—from Buddhist Jataka tales to Hindu epics, Islamic Pir Patas, and even Christian stories—alongside the diverse religious identities of the artists themselves (such as Islamic Patuas skillfully painting Hindu deities and narratives) highlight Patachitra’s role as a dynamic cultural interface.3 It was not a monolithic tradition but one that absorbed, reflected, and responded to the subcontinent’s complex and evolving religious and cultural tapestry. This capacity for absorption and adaptation is a fundamental reason for its survival and continued vibrancy across centuries of immense change.

Interestingly, periods of significant social upheaval or change often acted as catalysts for thematic and stylistic evolution within Patachitra, rather than solely leading to its decline. The emergence of new religions, the profound impact of colonialism, and the rise of competing forms of media, while posing existential threats, also spurred innovation. The vibrant Kalighat Pata, for instance, was a direct response to the burgeoning urban environment of colonial Calcutta and its unique social dynamics.15 This school of painting did not merely rehash old themes; it actively engaged with contemporary urban life, satirising new social classes and the pervasive influence of colonial power. Similarly, the Indian freedom struggle saw Patuas becoming visual chroniclers and inspirers, creating “songs of awakening” through their art.23 This pattern suggests that external pressures, while challenging, also fueled creative adaptation and forged new avenues of relevance for the art form.

A particularly fascinating aspect of Patachitra’s legacy is its potential, though perhaps under-acknowledged, influence on the nascent visual language of early Indian cinema. Descriptions of Patachitra as a “film strip defined via rhythmic-narration” 23 and its inherent structure of sequential narrative panels 7 point towards a foundational role in pre-cinematic visual storytelling. The performative element, especially in Bengal, where Patuas unrolled their scrolls in tandem with sung narratives, created an experience akin to a live, manually operated “movie”.3 This tradition of visual-oral performance, with its emphasis on sequential imagery to convey a story, likely contributed to the cultural milieu from which early Indian cinema, particularly in Bengal, drew its narrative and visual conventions.7

The Artisan’s Alchemy: Materials, Techniques, and Artistic Style

The creation of a Patachitra painting is a meticulous process, an alchemical transformation of simple, natural materials into vibrant narratives. This process, honed over centuries, is as much a part of the tradition as the final artwork itself.

The ‘Pata’ (Canvas): Preparation of Cloth and Palm Leaves

The traditional canvas, or ‘pata’, for these paintings is primarily cloth, usually cotton.2 The preparation is labour-intensive. Cotton fabric is often immersed in a solution of crushed tamarind (imli) seeds and water, or layered with tamarind paste to stiffen it.2 It is then coated with a mixture of chalk powder or fine clay powder blended with a natural gum, typically derived from wood apple (bael) or tamarind seeds.2 This coating creates a smooth, non-porous surface. The cloth is then sun-dried and meticulously polished, often with smooth stones like a ‘khaddar’ stone, followed by a ‘chikana’ stone, or sometimes shells, to achieve a resilient, leathery texture ideal for painting.2 While cotton remains traditional, silk is also used as a canvas, particularly in West Bengal, lending a different texture and sheen to the artwork.4

A distinct form, ‘Tala Patachitra’, is unique to Odisha and involves painting on palm leaves.6 For this, dried palm leaves are carefully cut to size, treated, and then stitched together to form a larger surface. Images are not painted in the conventional sense but are delicately incised or etched onto the hardened leaf surface using a sharp needle or metal stylus. These etchings are then filled with black ink or lamp soot to make the drawings visible, creating intricate and durable artworks.5

A Palette from Nature: The Sourcing, Creation, and Symbolism of Traditional Colours

The soul of Patachitra lies in its vibrant colours, traditionally derived entirely from natural sources such as minerals, plants, stones, lamp soot, and powdered conch shells.2 The preparation of these colours is a skill in itself:

- Black (Kala): Obtained from lampblack, created by collecting soot from a burning lamp or candle, or from burnt coconut shells or ‘Bhusakali’.2

- White (Sankha): Derived from powdered conch shells or seashells, or sometimes ‘Khorimati’ (a type of white clay).2

- Red (Hingula): Made from a mineral stone called ‘Hingula’ (cinnabar) or ‘Geru Pathar’ (red ochre).2

- Yellow (Haritala): Sourced from a native stone called ‘Haritala’ (orpiment) or ‘Holud Pathar’, or sometimes from turmeric.2

- Blue (Khandaneela/Nil): Extracted from the ‘Khandaneela’ stone, the Aparajita flower, or ‘Ramraja’ (indigo).2

- Green (Sabuja): Prepared from various green leaves, plants, or green stones.2

By skillfully mixing these primary pigments, artists can create a spectrum of around 120 different shades.2 These natural colours are typically mixed in wooden cups, often fashioned from coconut shells, further emphasising the use of natural products.2

The colours in Patachitra are not merely decorative; they are imbued with symbolism. The concept of ‘Pancha-Tatwa’ refers to the five primary colours (often black, white, red, yellow, and blue or green), which hold specific relevance. These colours can represent the five elements or, more commonly, the ‘Rasa’ (emotional essence) of the characters depicted in a narrative. For instance, ‘Hasya’ (laughter or mirth) is often depicted in white, ‘Raudra’ (anger or fury) in red, and ‘Adbhuta’ (amazement or wonder) in yellow.2 This symbolic use of colour enhances the storytelling, conveying emotional states and character attributes visually. The adherence to specific natural pigments for these key colours, especially in relation to divine figures like Jagannath, Balabhadra, and Subhadra, suggests that material choice and colour symbolism are not just aesthetic decisions but are integral to the art’s spiritual depth and narrative power.

The Art of Creation: A Step-by-Step Look at the Traditional Painting Process

The creation of a Patachitra is a disciplined art:

- Borders (Margin): A distinctive feature of Patachitra is the elaborate floral border, which is drawn first on all four sides of the prepared canvas. This border is considered a mandatory element and frames the central narrative.2 The borders from Raghurajpur in Odisha are particularly noted for their vibrancy and intricate designs.18

- Sketching (Rekha Chitra): Traditionally, many Patachitra artists, particularly the masters, did not make preliminary pencil sketches. They would directly begin outlining and filling in colours, a testament to their profound skill and familiarity with the iconography.4 However, some sources indicate that a light sketch might be made with a pencil or a fine brush dipped in a light pigment before the main colouring begins.2 The initial outlines are typically drawn with a fine brush or a thin reed pen, often using black pigment derived from burnt coconut shells.8

- Coloring (Ranga Bhara): Once the outlines are established, the artist begins to fill in the colors. The body colours of the figures are usually applied first, followed by their attire, and then the background.2

- Outlining (Motakala): After the base colours are applied and dried, the figures and details are meticulously outlined again, usually in black, to give them definition and sharpness.2

- Brushes (Tulika): The brushes used are traditionally handmade by the artists themselves. Fine brushes for delicate work are often made from mouse or squirrel hair, while coarser brushes for broader strokes or backgrounds might be made from buffalo hair or the fibrous roots of the Keya plant.2 The ability to create these specialized tools is part of the inherited knowledge of the Chitrakar.

- Coating (Jaulasa/Alankara): Finally, to protect the painting and give it a lasting sheen, a natural lacquer coating, known as ‘Jaulasa’, is often applied. This lacquer can be made from resin seeds or a tamarind seed paste.2

This traditional process, particularly the direct application of colour without extensive preliminary sketching, points to a highly developed, embodied skill. Such mastery is not learned from textbooks but is absorbed through years of practice and apprenticeship, typically within the family, passed down from one generation to the next.2 The Chitrakar is thus not merely an artist but a custodian of a complex set of traditional techniques and knowledge regarding material preparation and application.

Hallmarks of Patachitra: Exploring Characteristic Features

Patachitra paintings possess a distinct visual grammar:

- Lines: Characterised by bold, strong, crisp, and sharp lines that define the forms with clarity and confidence.5

- Colour Application: A rich and vibrant application of colour is typical, often with single-tone backgrounds that make the figures stand out.1

- Figure Portrayal: Figures are predominantly depicted in profile or semi-profile.1

- Perspective: There is a characteristic lack of perspectival recession or attempts at creating illusions of depth. This results in a deliberately two-dimensional appearance, where all incidents and figures are shown in close juxtaposition on the same plane.1

- Design Elements: Repetitive motifs and patterns are frequently used, lending a geometric quality to the compositions.2

- Detailing: The art form is renowned for its intricate details and meticulous craftsmanship, with every element carefully rendered.2

- Compositional Device: Many works feature a festooned fabric painted across the top, suggestive of an enclosed shrine, a stage, or a protective curtain drawn back to reveal the deity or narrative scene within.1

The “rules” of composition, such as the general avoidance of landscapes, the preference for profile figures, and the mandatory floral borders, contribute to this distinct visual language that reinforces its traditional identity and makes it instantly recognisable.5

The traditional reliance on locally sourced, natural materials—plants, minerals, and shells for colours; cotton for the canvas; tamarind seeds for paste—made Patachitra an inherently sustainable art form in its original context.2 This practice resulted in a minimal ecological footprint and generated little waste, with even old cotton cloth being repurposed for canvases.18 This inherent sustainability, viewed through a modern lens, is a significant aspect of its heritage, contrasting sharply with many contemporary art material practices.

Stories Woven in Hue: Themes, Narratives, and Iconography

Patachitra paintings are, at their heart, visual narratives. The themes predominantly draw from a vast reservoir of Hindu mythology, epics, Puranic tales, local folklore, and, particularly in Bengal, contemporary social and political events.

Divine Narratives: Depictions from Hindu Epics, Puranic Tales, and Deities

The Jagannath cult is a central and defining theme, especially in Odisha Patachitra. These paintings vividly depict Lord Jagannath, his brother Balabhadra, and sister Subhadra, in their iconic forms with large, round eyes and distinct facial features.1 The grand Jagannath temple in Puri, its rituals like the Rath Yatra (chariot festival), and the ‘Anasara’ period (when the deities are in seclusion and represented by paintings) are frequent subjects.1 It is believed that the story of these three divine siblings was first visually narrated on Pattachitra.2

Stories of Krishna Lila are immensely popular, showcasing the playful and divine life of Lord Krishna. These include his childhood antics, his divine romance with Radha and the Gopis (milkmaids), and scenes inspired by Jayadeva’s epic poem, the Gita Govinda.2

The great Indian epics, the Ramayana and Mahabharata, provide an inexhaustible source of narratives for Patachitra artists. Key events, characters, and moral lessons from these epics are meticulously illustrated.1 The Dashavatara, or the ten incarnations of Lord Vishnu, is another frequently depicted theme, showcasing the god’s various manifestations to restore cosmic order.1

Forms of Shakti, the divine feminine principle, are also prominent. Goddesses like Durga, especially in her form as Mahishasuramardini (slayer of the buffalo demon), are central to Bengal Patachitra, with ‘Durga Pat’ being a specific genre.3 Other goddesses like Kali, Manasa (serpent goddess), and Chandi also feature regularly.3 Other deities from the Hindu pantheon, such as Ganesha (the elephant-headed god of beginnings) and Shiva, along with a multitude of stories from the Puranas (ancient Hindu scriptures), enrich the thematic repertoire of Patachitra.1

The common practice of depicting multiple scenes or entire narrative arcs within a single scroll or canvas, sometimes in a “compartmentwise” manner, underscores Patachitra’s primary function as a storytelling and educational medium rather than purely decorative art.1 This narrative density, particularly when combined with the performative song tradition in Bengal, suggests a strong didactic intent: to teach, inform, and propagate cultural and moral values to a wide audience, many of whom in earlier times might have been illiterate.16

Echoes of Local Lore: Representation of Regional Folklore and Folk Deities

Beyond the pan-Indian epics, Patachitra art also gives vibrant expression to regional folklore and local deities. In Bengal, tales like those of Manasa and Chandi, and the poignant story of Behula and Lakshinder, are popular subjects.3 The art form also embraces tribal stories and rituals. Santhal Pattachitra, for instance, often depicts themes of nature, scenes from daily tribal life, and representations of ‘Bondeya’ or forest spirits.9 ‘Yama Patas’, illustrating Yama, the God of Death, and the consequences of one’s actions in the afterlife, served as powerful tools for moral instruction.23 In regions with Sufi influence, ‘Musalmani Patas’ narrating the tales of Pirs (Sufi saints) and Gazis (warriors) also found expression.23

The consistent depiction of deities with specific, recognisable attributes—such as Lord Jagannath’s characteristic round eyes and black face, or Krishna often shown in blue and Rama in green—along with the symbolic use of colours to denote emotions (Rasa), created a standardised and accessible visual language.1 This iconographic standardisation ensured that the narratives were readily understandable to diverse audiences, reinforcing shared cultural knowledge and making the art form an effective communication tool, especially for pilgrims from various regions and for community education.

The Canvas as a Mirror: Patachitra’s Engagement with Social, Political, and Contemporary Themes

Patachitra, particularly in its Bengali manifestation, has demonstrated a remarkable capacity to engage with the immediate social, political, and contemporary realities of its time. Artists have used their scrolls to comment on and raise awareness about a wide array of issues, including literacy, health, environmental concerns, women’s rights, child rights, family planning, and the dowry system, and to condemn practices like female feticide.3

Historically, Bengal Patuas chronicled significant political events, such as the Indian freedom struggle, the Bengal Famine, various wars, and the partition of India.23 The satirical Kalighat Pata tradition offered sharp critiques of the colonial ‘Babu culture’.3 This responsiveness continues into the modern era, with Patachitra artists depicting events of national importance like India’s Chandrayaan lunar expeditions, and global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, often creating scrolls with accompanying songs to explain and raise awareness.7 Even modern Odisha Patachitra has expanded its thematic horizons to include contemporary events like the World Trade Centre attack, depictions of life in modern Odisha, and philosophies of other faiths like Buddhism, Jainism, and Christianity.10

This engagement with contemporary issues, especially prominent in Bengal, positions the Patuas as vital chroniclers of subaltern history and public discourse. They have consistently given voice to the experiences and concerns of common people, documenting social changes and historical moments from a grassroots perspective.16 This makes Patachitra not just a preserver of ancient tales but also a dynamic and relevant medium for commenting on and recording the lived realities of its time.

Two Streams, One Tradition: Patachitra of Odisha and Bengal

While Patachitra is a unifying term for cloth-based scroll painting from Eastern India, the traditions of Odisha and Bengal, though sharing common roots, have evolved into distinct artistic expressions, each with its unique characteristics.

Shared Roots, Distinct Identities: Commonalities in Heritage and Artistic Philosophy

Both Odia and Bengali Patachitra originate from the same etymological foundation: ‘Pata’ (cloth) and ‘Chitra’ (painting).1 Both are ancient art forms deeply rooted in the narration of mythological folktales.18 Traditionally, artisans in both regions have employed natural colours and are renowned for their intricate detailing and the inclusion of elaborate floral borders in their compositions.18 The artists are generally known as ‘Chitrakars’, though the term ‘Patua’ is more commonly associated with the artists of Bengal.1 In recent times, both Odisha Pattachitra and Bengal Patachitra have witnessed a diversification of products to cater to modern markets, and significantly, both Odisha Pattachitra and Bengal Patachitra have been accorded Geographical Indication (GI) tags, recognising their unique regional identities and heritage.27

A Comparative Look: Differences in Materials, Themes, Style, and Storytelling

Despite these commonalities, notable differences exist across several aspects:

- Materials:

- Odisha: The primary canvas is cotton. A unique feature of Odisha is ‘Tala Patachitra’, where paintings are incised on palm leaves.6

- Bengal: Traditionally, old cotton cloth was used. Nowadays, artists often use paper, frequently backed with cloth for durability. Silk is also a favoured canvas material in Bengal.6

- Primary Themes:

- Odisha: There is a strong and central focus on Lord Jagannath, the holy trinity (Jagannath, Balabhadra, Subhadra), temple rituals, and stories from the life of Lord Krishna (Krishna Lila), as well as narratives from the Ramayana and Mahabharata. A high degree of accuracy in iconographic representation is emphasised.1 Depictions of the traditional Gotipua dance form are also a specific feature.18

- Bengal: The thematic range is broader. While Hindu mythology (featuring deities like Durga, Kali, Krishna, and narratives from the Ramayana and Mahabharata) is central, Bengali Patachitra also extensively incorporates local folklore (tales of Manasa, Chandi), Sufi traditions, and, very significantly, contemporary social, political, and environmental issues. A sense of boldness and directness is often evident in these depictions.3

- Stylistic Nuances:

- Odisha: Characterised by extremely intricate and delicate linework, with elegant and finely detailed borders. The overall detailing is generally more profuse and refined.5 The colour palette traditionally includes black, red, yellow, and orange, with indigo being a later addition.6

- Bengal: Known for bolder lines, often thicker borders, and a certain brevity or stylisation in representation. The colours are typically vibrant and contrasting, creating an eye-catching effect. The detailing, while present, may be less dense than in Odisha Patachitra. Favourite traditional colours include white, yellow, blue, green, red, brown, and black.5

- Artist’s Role and Storytelling Method:

- Odisha: The Chitrakars are primarily painters. While their paintings are inherently narrative, the performative aspect of singing the story is not as central or defining as it is in the Bengal tradition.18

- Bengal: The Patuas are traditionally versatile artists, often functioning as painters, lyricists, singers, and performers. A hallmark of Bengal Patachitra is the practice of travelling from village to village, unfurling their painted scrolls, and narrating the depicted stories through songs known as ‘Pater Gaan’ or ‘Patua Sangeet’.3

- Lifestyle of Patuas/Chitrakars (Notable Village Examples):

- Naya (Bengal): In this prominent Patua village, women are increasingly taking a leading role in the Patachitra tradition. They are actively involved in Pata making, storytelling through song, and the marketing and selling of their artwork, often working independently alongside men.18

- Raghurajpur (Odisha): In this heritage crafts village, while women participate significantly in Pata making (especially in preparatory work like color and canvas preparation, and filling in colors), the men typically handle the initial sketching, the final finishing of the Pata, and are predominantly responsible for the selling and marketing aspects. Women’s roles, while crucial, are often more in the “backdrop” of the business side.18

This comparison highlights that while Odisha Patachitra places a strong emphasis on the iconographic sanctity and ritualistic use of the painted object itself, particularly in connection to the Jagannath cult, Bengal Patachitra’s defining characteristic is often its performative storytelling, making the Patua a multifaceted artist whose role extends beyond painting to singing and narration.1 This difference suggests a fundamental divergence in the primary mode of cultural transmission and the artist’s societal role. In Bengal, the art is often a vehicle for a live, oral-visual performance, whereas in Odisha, the art object itself frequently holds direct ritualistic power.

The thematic divergence also appears to reflect the distinct socio-cultural milieus of the two regions. Odisha Patachitra’s strong thematic concentration on Lord Jagannath and classical Hindu epics suggests a tradition that is more centralised and deeply intertwined with a specific, powerful religious institution.1 In contrast, Bengal Patachitra’s broader thematic canvas—embracing local folklore, Sufi influences, and extensive social and political commentary—points to a more decentralised, socially embedded, and perhaps more fluidly adaptive artistic practice.3 This thematic flexibility in Bengal, coupled with the often itinerant nature of its Patuas and their engagement with a wide array of subjects, could be a key factor in its historical resilience and its capacity to absorb and reflect diverse influences, including the varied religious backgrounds of the artists themselves.3 The differing roles and visibility of women artists in key villages like Naya (Bengal) and Raghurajpur (Odisha) also hint at varying social structures that influence the practice and business of the craft.18

Even the material choices can be seen as subtle cultural markers. The prominent use of cotton and the unique tradition of palm leaf etching (Tala Patachitra) in Odisha signify specialised regional skills and material preferences.6 Bengal’s more varied use of cotton, paper (often backed with cloth for scrolls), and silk might reflect adaptations for wider accessibility, different market demands, or influences from other rich Bengali textile traditions.6 These choices, while seemingly practical, contribute to the distinct artistic identities of each region.

Comparative Overview: Odisha Patachitra vs. Bengal Patachitra (Patua Art)

| Feature | Odisha Patachitra | Bengal Patachitra (Patua Art) |

| Primary Canvas | Cotton, Palm Leaf (Tala Patachitra is unique to Odisha) 6 | Traditionally, old cotton, now often paper (cloth-backed for scrolls), Silk is also used 6 |

| Dominant Themes | Jagannath cult (Lord Jagannath, Balabhadra, Subhadra, temple rituals), Hindu epics (Ramayana, Mahabharata), Krishna Lila, Puranic stories. Focus on iconographic accuracy. Depictions of the Gotipua dance form. 1 | Hindu epics, regional Bengali folklore (Manasa, Chandi, Behula-Lakshinder), Sufi traditions, extensive social & political commentary, current events, environmental issues. Focus on narrative boldness. 3 |

| Stylistic Elements | Extremely intricate, very fine and delicate lines, detailed and elegant floral borders. Colour palette often includes black, red, yellow, and orange, with indigo added later. 5 | Bolder lines, often thicker borders, a degree of brevity or stylisation in representation, vibrant and contrasting eye-catching colours. Palette includes white, yellow, blue, green, red, brown, and black. 5 |

| Artist’s Role & Storytelling | Chitrakars are primarily painters. The narrative is inherent in the visual depiction. Performative singing is not a defining characteristic. 18 | Patuas are traditionally versatile: painters, lyricists, singers, and performers. Storytelling is a key function, often through “Pater Gaan” (unfurling the scroll while singing the narrative). 3 |

| Key Artist Villages | Raghurajpur, Puri district 10 | Naya village (Pingla block, Paschim Medinipur district) 7 |

Beyond Decoration: The Socio-Cultural and Religious Significance of Patachitra

Patachitra art transcends its aesthetic appeal, holding profound socio-cultural and religious significance in the regions where it flourishes. It is deeply embedded in the ritualistic life of communities, serves as a powerful medium for education and moral instruction, and is a testament to the enduring legacy of hereditary artisan communities.

Art in Ritual: Patachitra’s Role in Temple Worship, Festivals, and as Sacred Objects

In Odisha, Patachitra is integral to the rituals of the famed Jagannath Temple in Puri. Perhaps its most crucial ritualistic role is the creation of ‘Anasara’ paintings. During the ‘Snana Yatra’ (ritual bathing festival), the main deities of Lord Jagannath, Balabhadra, and Subhadra are believed to fall ill and are kept in a 15-day seclusion period known as ‘Anasara’. In this interim, Pattachitra representations of the deities are worshipped by devotees.2 Furthermore, vibrant Patachitra paintings adorn the massive wooden chariots used in the annual Rath Yatra festival, transforming them into mobile temples of art.2 These paintings are considered sacred and are sometimes used in secret worship rituals within the temple precincts.5 The ‘Yatripatas’, or pilgrim souvenirs, carried home by devotees, also function as sacred objects, acting as conduits for continued devotion and remembrance of the divine.1

In Bengal, Patachitra also plays a significant role in religious observances. The ‘Durga Pat’ or ‘Durga Sara’ (a specific type of Pata depicting Goddess Durga and her exploits) is revered and worshipped during the major festival of Durga Puja.3 ‘Chalchitra’, another form of Pata painting, traditionally serves as the ornate backdrop for Durga idols during the Puja.3 Among certain tribal communities like the Santhals, a unique Pata known as ‘Chakshudan Pat’ is used in death rituals. In this practice, the artist paints the image of the deceased but leaves the eyes blank. Only after receiving payment or as part of the ritual does the artist paint the eyeballs, an act believed to “give sight” to the soul for its journey into the afterlife.23 ‘Yama Patas’, depicting Yama, the god of death, and scenes of heaven and hell, served as potent tools for moral instruction, visually reinforcing concepts of karma and righteousness.23 For communities, especially in pre-literate or semi-literate contexts, these Patachitra scrolls, particularly when combined with oral narration, effectively functioned as accessible, visual sacred texts. They made complex mythologies, moral codes, and religious tenets understandable and relatable, acting as active conduits of religious knowledge and cultural values, much like written scriptures but in a more immediate visual and oral format.16

Visual Storytellers: The Function of Patachitra in Community Education, Moral Instruction, and Oral Tradition

Historically, Patachitra served as a crucial visual device for storytelling, particularly for villagers who might have been illiterate.3 The Patuas of Bengal, in particular, were itinerant storytellers. They would travel from village to village with their painted scrolls, narrating stories from the epics (Ramayana, Mahabharata), Puranas, local folklore, and even contemporary social issues through captivating songs known as ‘Pater Gaan’.3 This tradition not only entertained but also played a vital role in preserving ancient stories, cultural traditions, and moral values, passing them down through generations.16 Patachitra thus became a medium for disseminating cultural memory and the intangible aspects of a community’s heritage.17 The tradition of Patuas travelling and performing in villages likely played a significant role in fostering community cohesion. By reinforcing shared narratives, values, and cultural identity across different localities, the communal experience of watching and listening to these stories would have strengthened social bonds, making the art form a kind of social adhesive, particularly in rural, dispersed communities.3

Even today, this educational role continues, with Patachitra being used as a medium for raising awareness on contemporary social issues such as health, literacy, environmental conservation, and women’s rights.3 The ‘Chakshudan Pat’ ritual further illustrates a dimension where the artist’s role transcends mere representation to become one of ritual efficacy. The act of the Patua painting the eyes onto the image of the deceased is believed to have a transformative spiritual impact, facilitating the soul’s passage. This imbues the artist with a quasi-priestly or shamanic function, highlighting a layer of religious significance that goes deeper than just illustrating known myths.23

A Hereditary Legacy: The Role of Chitrakar and Patua Communities in Preserving and Perpetuating the Art Form

Patachitra is predominantly a hereditary art form, with the intricate skills and knowledge passed down through generations within families and communities of ‘Chitrakars’ (in Odisha and also used in Bengal) and ‘Patuas’ (primarily in Bengal).1 Entire villages, such as Raghurajpur in Odisha and Naya in West Bengal, have become renowned as hubs where virtually the entire community is devoted to the practice of Patachitra, creating a unique ecosystem for the art’s survival and evolution.5 Artists often carry the occupational surname ‘Chitrakar’, signifying their ancestral connection to the craft.35 This deep-rooted community involvement ensures the continuity of techniques, themes, and the cultural ethos associated with Patachitra.

Patachitra in the 21st Century: Evolution, Challenges, and Resilience

The ancient art of Patachitra continues to navigate the complexities of the 21st century, demonstrating remarkable resilience through adaptation while facing significant challenges to its traditional forms and the livelihoods of its practitioners.

Adapting to Modernity: Innovations in Themes, Materials, and Forms

One of the most striking aspects of Patachitra’s contemporary journey is its thematic evolution. While traditional mythological narratives remain a cornerstone, artists have increasingly embraced contemporary social issues. Scrolls now address topics such as women’s rights, child rights, literacy, public health (including HIV/AIDS awareness), environmental conservation, trafficking, female feticide, and the dowry system.3 Political commentary and depictions of current events, from national achievements like the Chandrayaan lunar missions to global incidents like the World Trade Centre attacks and the COVID-19 pandemic, have also found their way onto the ‘pata’.7

In terms of materials, while the use of traditional natural dyes and hand-prepared canvases is still highly valued and taught as part of the heritage 33, some artists have adopted modern synthetic paints like acrylics and watercolours. These offer convenience, a broader ready-made palette, and faster drying times, though there is an awareness that they may alter the traditional feel and long-term archival quality of the work.24 Commercially available canvases are also sometimes used as an alternative to the labour-intensive traditional preparation process.24

The forms of Patachitra have also diversified significantly. Beyond the traditional scrolls and square ‘patas’, the art now adorns a wide array of products. These include textiles like sarees, T-shirts, kurtis, and dupattas; home decor items such as lampshades, serving trays, flower vases, kettles, and coasters; and accessories like bags, jewellery, and even face masks.5 The tradition of painting Ganjifa (playing cards), masks, coconut shells, and bamboo boxes also continues and has found new markets. Single-panel paintings, designed to be framed and displayed as standalone artworks, are increasingly common, catering to modern aesthetic preferences.7 The Kalighat Pattachitra of Bengal, itself an urban evolution influenced by Western art and social realism, continues to inspire contemporary expressions.3 Furthermore, artists are exploring digital avenues, using social media platforms like Facebook for sales and promotion, and some are even creating digital versions of Patachitra art.12

The Artist’s Predicament: Economic Challenges, Market Access, and Competition

Despite its cultural richness and adaptability, the Patachitra tradition faces numerous challenges, particularly concerning the economic well-being of its artists. Many Patuas and Chitrakars continue to live in poverty or with very modest means, grappling with weak financial power and difficulties in accessing formal credit from banks. This often forces them into dependence on local moneylenders who charge exorbitant interest rates, further trapping them in cycles of debt.23

Market access remains a significant hurdle. There is often a lack of organised marketing processes, and artists may lack the financial resources or business acumen to effectively promote their work or attend lucrative fairs and exhibitions.36 Middlemen and dealers frequently dominate the supply chain, purchasing artworks from artists at low prices and selling them in urban or international markets for considerably higher sums, with only a small fraction of the profit reaching the creators.33

Competition from mass-produced goods and modern media also poses a threat. Cheap machine-made prints, such as oleographs, historically contributed to the decline of traditions like Kalighat Pata.16 The advent of television, the internet, and cinema has also reduced the demand for the traditional performative storytelling aspect of Patachitra, particularly in Bengal.3

Furthermore, some artists, particularly in more remote communities, may have limited formal education or lack modern business skills, including computer literacy, making it difficult for them to manage inventory, access government welfare schemes, or negotiate effectively with traders.36 There can also be a perception issue, where sophisticated urban consumers sometimes devalue rural folk art forms.37 This creates a tension for artists who are pressured to adapt their traditional styles to meet contemporary market demands, which can sometimes lead to concerns about the dilution of the art form’s unique characteristics and the potential loss of its oral-visual storytelling essence.37

This diversification into a wide array of consumer products, while a crucial economic survival strategy, presents a complex scenario. On one hand, it provides much-needed income and broader market visibility. On the other hand, it risks commodifying and decontextualising an art form that is deeply rooted in narrative, ritual, and community performance. A mythological scene painted on a traditional scroll carries a different cultural weight and function than a simplified motif on a T-shirt or a coaster.1 The challenge lies in ensuring that adaptation for economic viability does not lead to an irreversible erosion of the art’s core cultural significance and its rich narrative traditions.

Nurturing the Flame: Initiatives for Preservation and Promotion

In response to these challenges, various initiatives have emerged to preserve, promote, and revitalise Patachitra art. Artist collectives, such as “Chitrataru” in Naya village, West Bengal, have been formed by the artists themselves to strengthen their agency and market presence.34 Entire villages, like Raghurajpur in Odisha and Naya in West Bengal, continue to function as dedicated craft hubs, fostering a supportive environment for the artists.10

Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) play a vital role. Organisations like Contact Base in Kolkata, with its ‘Art for Life’ model, the Raksh Folk Arts Of India Foundation, and the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH), provide crucial support through training, design development, market linkages, and safeguarding initiatives.12

Government bodies, including the Ministry of Culture at the national level, and state governments (such as the Department of MSME&T in West Bengal), along with institutions like the Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre (EZCC), have also stepped in. They offer subsidies, support training programs for design upgradation and product diversification, and organise platforms like fairs and festivals (e.g., the annual Patachitra Mela or POT Maya in Naya) to showcase and sell the artists’ work.12 International organisations like UNESCO have also been involved in projects such as the Rural Craft Hub initiative, which has benefited Patachitra communities.7

A significant development for the protection and promotion of Patachitra has been the awarding of Geographical Indication (GI) tags to both Odisha Pattachitra and Bengal Patachitra.27 The GI tag is a form of intellectual property right that recognises products originating from a specific geographical location and possessing unique qualities or a reputation attributable to that origin. It aims to protect the authenticity of the art form, preserve its cultural heritage, promote the products, and potentially offer economic benefits to the artisans by preventing unauthorised copying and enabling them to command premium prices in the market.30 A GI tag can enhance marketability and build consumer confidence in the authenticity of the craft.30 However, the actual economic impact of the GI tag on grassroots artists can sometimes be limited by factors such as a lack of awareness among producers about the registration process and its benefits 41, persistent issues with market linkage, and the continued dominance of middlemen in the trade.33 There often appears to be a gap between the legal provision of the GI tag and its effective implementation in a way that directly and substantially benefits the artisan communities economically. The power of the GI tag might remain underutilised if artists are not adequately empowered to leverage it or if the existing supply chains do not ensure fair returns.

Festivals and exhibitions, such as the POT Maya in Naya, the Satrangi exhibition series, showcases at the ZEE Jaipur Literature Festival, and a recent exhibition focused on the revival of Sunderbans Patachitra, provide important platforms for visibility and sales.25 Efforts are also being made to ensure the transmission of skills to younger generations, for instance, through training programs at community centres like the one supported by UNESCO in Naya.7

Despite these positive developments, a resilience paradox often emerges: while some individual Patachitra artists achieve national and even international recognition and secure better earnings, the broader community of Patuas and Chitrakars frequently remains economically vulnerable.33 There are inspiring stories of artists like Saramuddin Chitrakar earning a significant sum for a commissioned piece, or Radha Chitrakar building a permanent house with her earnings from international sales and performances.33 These successes demonstrate the potential of the art form. However, the general narrative often still includes widespread poverty and ongoing struggles for many practitioners. This indicates a disparity where the increasing cultural capital and recognition of Patachitra art do not always translate into widespread economic upliftment for all its creators. Systemic issues related to fair pricing, direct market access, and equitable distribution of profits persist for a large segment of the artisan community.

Masters of the Scroll: Notable Artists and Esteemed Collections

The Patachitra tradition, both in Odisha and Bengal, has been nurtured and carried forward by generations of skilled artists. While the art is often a community-based practice, several individuals have gained prominence for their mastery, innovation, and dedication to preserving this heritage.

Celebrating the Torchbearers: Profiles of Influential Traditional and Contemporary Patachitra Artists

Odisha:

The Patachitra artists of Odisha, often hailing from villages like Raghurajpur, are renowned for their intricate work, particularly centred around the Jagannath cult.

- Raghunath Mohapatra: A highly renowned master artist and sculptor, recipient of some of India’s highest civilian honours. While primarily known for stone carving, his work is deeply rooted in the traditional Odia artistic lexicon that also informs Pattachitra.13

- Apindra Swain: A contemporary artist known for his Pattachitra and Talapatra (palm leaf etching) work. He is also involved in teaching, conducting masterclasses to pass on the traditional skills.3 His works often depict Ganesha, Radha-Krishna, Dashavatara, and scenes from the Ramayana.

- Purusottam Swain: Another significant contemporary artist whose repertoire includes detailed narrations of the Ramayana, depictions of the Puri Rath Yatra, Krishna Leela, and the life of Sri Chaitanya.3

- Sanju Swain: Noted for expertise in the intricate art of Talapatra Pattachitra, particularly works featuring the Jagannath Temple.44

- Gitanjali Das: A contemporary Pattachitra artist contributing to the living tradition.44

- Bamadeb Das: A sixth-generation Pattachitra artist from the heritage village of Raghurajpur, actively practising and showcasing the art.28

- Rabi Behra: An artist whose Pattachitra works have gained global recognition, serving as an inspiration for other artists in the field.5

- Apana Maharana: While not a painter in the same vein, his historical sketchbook containing traditional Odissi drawings from Jeypore, Koraput, is considered a valuable collection related to the artistic traditions of the region.26

The dynastic nature of this artistic lineage is very evident in Odisha, with skills and specific iconographic knowledge meticulously passed down from father to son, often within close-knit family units.13 This ensures a deep continuity of tradition but historically might have made it challenging for those outside these hereditary lines to enter the practice.

West Bengal (Patuas/Chitrakars):

The Patuas of West Bengal, concentrated in villages like Naya in Paschim Medinipur district, are known for their narrative scrolls and accompanying songs.

- Jamini Roy: A seminal figure in modern Indian art, Jamini Roy was not a traditional Patua but was deeply influenced by Bengali folk art, including Kalighat Pattachitra. He played a crucial role in popularising and reinterpreting these folk idioms, developing the Kalighat Pattachitra tradition and influencing its modern thematic explorations.3

- Khandu Chitrakar and Radha Chitrakar: Along with their children—Bapi, Samir, Prabir, Laltu, Tagar, Mamoni, and Laila Chitrakar—this family represents the hereditary nature of the art in Bengal.35

- Laltu Chitrakar: Known as a contemporary Kalighat painting artist.45

- Manoranjan Chitrakar: A Bengal Pattachitra artist who also conducts masterclasses, sharing his knowledge of the form. His works include depictions of Lakshmi, Ganesha, and Durga.3

- Swarna Chitrakar: One of the most celebrated contemporary women Patuas from Naya. She is renowned for her artworks that often address gender issues, social problems like trafficking and female foeticide, and other contemporary themes, alongside traditional narratives. Her work has gained national and international recognition.3

- Anwar Chitrakar: A notable Kalighat painter whose works have been exhibited internationally, including at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. He was a recipient of the Ojas Art Award.31

- Uttam Chitrakar: A Kalighat artist who also teaches masterclasses, contributing to the dissemination of this style. He was a recipient of the Ojas Art Award.3

- Veteran Artists of Naya: The village of Naya is home to many skilled artists, including Khadu Chitrakar (who learned from his father Baneswar and grandfather Dari Chitrakar), Saramuddin Chitrakar (known for large Ramayana Patas), Bahar Chitrakar (an acclaimed artist and poet), Ajoy Chitrakar, and Shajahan Chitrakar (creator of a notable Pata on the COVID pandemic).33 Rahim Chitrakar is another renowned artist from Naya.33

- Kalam Patua: An artist credited with helping to revive the endangered Kalighat Gharana (school) of painting. His works have also been displayed internationally.23

- Historical Kalighat Artists: The foundations of Kalighat painting were laid by artists such as Bhawanipur Sitaldas, Gobardhan Bhattacharya, Harinarayan Chattopadhyay, and Kali Prasad Ghosh. Nandalal Bose, another giant of Indian modern art, also worked in and was influenced by the Kalighat style.45

A significant trend, particularly noticeable in Bengal, is the emerging prominence of women Patuas. While Pattachitra, especially in its Odishan form, was historically a male-dominated field 13, women artists like Swarna Chitrakar, Radha Chitrakar, and others from the families in Naya (Mamoni, Laila, Tagar) are now at the forefront, gaining recognition for their skill and often bringing fresh perspectives to the thematic content.18 This marks an important socio-cultural evolution within these artisan communities, broadening the creative voices and challenging traditional gender roles.

The careers of many contemporary Patachitra artists, both in Odisha and Bengal, appear to be significantly supported and amplified by the efforts of NGOs, government initiatives, and dedicated art platforms or awards.19 This suggests a symbiotic relationship where external support systems are becoming increasingly crucial for providing visibility, market access, and formal recognition to individual artists and to the art form as a whole, helping them navigate the contemporary art world.

Where to Witness Patachitra: Mention of Significant Museum Collections, Galleries, and Exhibitions

Patachitra art can be appreciated in various museums, galleries, and at specific cultural events:

- Museums:

- Odisha State Museum, Bhubaneswar: This museum houses a substantial collection of Pata paintings, including traditional Ganjapas (playing cards), iconic Odia motifs like Navagunjara and Kanchi Vijaya, scenes from the Krishnalila, Ramayana, Dashavatara, and large, unique temple depictions.11

- National Museum of Ethnology, Lisbon, Portugal: This museum holds a collection of Patachitra from Naya village, West Bengal, indicating international interest in this art form.11

- Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK: Has exhibited works by contemporary Bengal Patuas like Anwar Chitrakar.45

- Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, Australia: Has displayed paintings by Kalighat artist Kalam Patua.45

- Numerous other museums and private collections worldwide hold examples of Patachitra, particularly the historical Kalighat paintings.16

- Galleries & Exhibitions:

- Historically, exhibitions were staged at Puri Town Hall (1953) and in Delhi and Calcutta (1954) under the aegis of the American Friends Service Committee, with support from figures like the then Chief Minister of Odisha, Nabakrishna Choudhary, aimed at reviving this indigenous art.5

- The Ojas Art Award, presented at the ZEE Jaipur Literature Festival, has periodically focused on indigenous art forms, including Bengal Patachitra (which was the focus in 2018). Awardee’s works are subsequently showcased in the “Satrangi” exhibition in Delhi.31

- The Patachitra Mela (fair), also known as POT Maya, is an important annual event held in Naya village, Paschim Medinipur, West Bengal. Organised with State government support, it has grown significantly and serves as a major platform for the Naya Patuas to showcase and sell their art, and perform their Pater Gaan.25

- A notable recent exhibition highlighted the revival efforts for Sunderbans Patachitra, supported by the West Bengal forest department and organised by the Kolkata Society for Cultural Heritage, showcasing works by women artists from villages near the Sunderbans Tiger Reserve.43

- Online platforms and galleries like MeMeraki play a crucial role in showcasing and selling works by contemporary Patachitra artists such as Apindra Swain, Purusottam Swain (Odisha), Manoranjan Chitrakar, and Swarna Chitrakar (Bengal).3

- The Lalit Kala Akademi’s regional centre in Kolkata also hosts exhibitions and ‘melas’ (fairs) that include Patachitra artists.19

These collections and exhibitions are vital not only for the appreciation of Patachitra by a wider audience but also for providing economic opportunities for the artists and for the scholarly study and preservation of this rich artistic heritage.

Conclusion: The Unfurling Future of a Timeless Art

Patachitra, in its vibrant hues and intricate narratives, stands as a testament to the enduring cultural value and artistic richness of Indian folk traditions. It is far more than mere “cloth-painting”; it is a multifaceted phenomenon that has served as a dynamic storytelling medium, an integral part of sacred rituals, a vivid historical chronicle, and a profound expression of cultural identity for centuries.1 Its journey from ancient temple precincts and village squares to contemporary art markets and digital platforms reflects an extraordinary resilience and an innate capacity for evolution.

The interplay between deeply rooted tradition and thoughtful contemporary adaptation is central to Patachitra’s continuing story. Artists today, like their predecessors, navigate the delicate balance between preserving the sacredness of their ancestral heritage—the meticulous techniques, the natural colour palettes, the iconic mythological themes—and responding to the demands and dialogues of the modern world.3 This negotiation is evident in the expansion of thematic concerns to include pressing social issues and current events, the cautious adoption of new materials, and the diversification of artistic forms to engage new audiences and markets.

The entire trajectory of Patachitra, from its ancient origins through its regional diversifications and into its modern manifestations and challenges, offers a compelling case study of how traditional art forms negotiate their space and relevance in a rapidly changing global landscape. It embodies the inherent tensions between the pursuit of authenticity and the necessity of adaptation, between ritualistic significance and commercial viability, and between the preservation of local identity and the engagement with global influences.1 This is a narrative familiar to many folk arts worldwide, and Patachitra’s story provides valuable insights into the dynamics of cultural continuity and change.

Looking ahead, the future of Patachitra appears to lie in embracing a hybrid identity—one that consciously draws strength and inspiration from its rich traditional wellspring while creatively and courageously engaging with new themes, innovative forms, and emerging platforms.12 The success of artists who skillfully blend traditional techniques with contemporary narratives, or who adapt their ancient craft to new products without entirely losing its essence, points towards this hybrid path as the most viable for sustained vitality. The ongoing efforts by artisan communities, supportive NGOs, government bodies, and cultural organisations to preserve traditional skills while fostering innovation are crucial in this endeavour.

Patachitra remains a “living heritage,” a vibrant artistic expression that continues to foster dialogue, celebrate life, and connect generations.3 Its unfurling scrolls still have many stories to tell, and its enduring spirit, characterised by both tenacity and adaptability, suggests that this timeless art will continue to captivate and enrich audiences across India and the world for generations to come.

Disclaimer

This article on Patachitra art has been compiled and written based on the research material provided. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy and comprehensiveness in interpreting this material, the article represents an understanding derived from these specific sources. Patachitra is a vast and ancient art form with diverse regional expressions and a continuously evolving tradition. This article aims to provide an informative overview and should be considered a snapshot based on the available information. Further research and engagement with the artists and cultural custodians are always encouraged for a deeper appreciation of this rich heritage.

Reference

- Pattachitra : The University of Western Australia, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.uwa.edu.au/lwag/exhibitions/expressions-of-india/pattachitra

- History & Significance of Pattachitra Paintings l iTokri आई.टोकरी, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://itokri.com/blogs/craft-masala-by-itokri/magnificent-pattachitra-paintings-of-orissa

- A journey into Bengal Pattachitra- Blog – MeMeraki, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.memeraki.com/blogs/posts/unfurling-a-world-of-wonder-a-journey-into-bengal-pattachitra

- The Timeless Beauty of Patachitra Painting: A Glimpse into India’s Art, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://shringhaar.com/blogs/all/the-timeless-beauty-of-patachitra-painting-a-glimpse-into-indias-artistic-heritage

- Pattachitra: An Ancient Folk Art that Reflects the Ethos of India, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.exoticindiaart.com/blog/pattachitra-an-ancient-folk-art-that-reflects-the-ethos-of-india/

- Pattachitra paintings: visual storytelling device from Odisha – Chitrapata, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://chitrapata.in/pattachitra-paintings-visual-storytelling-device-of-odisha/

- Bengal Patachitra weaves tales of resilience and expression, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.villagesquare.in/bengal-patachitra-weaves-tales-of-resilience-and-expression/

- How Pattachitra Art Brings Indian Epics to Life? – Cottage9, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.cottage9.com/blog/how-pattachitra-art-brings-indian-epics-to-life/

- The Enchanting World of Pattachitra Art: Article – MeMeraki, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.memeraki.com/blogs/posts/the-enchanting-world-of-pattachitra-art

- Pattachitra – Craft Archive | Research on Indian Handicrafts …, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://gaatha.org/Craft-of-India/research-study-pattachitra-raghurajpur/

- Pattachitra – Wikipedia, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pattachitra

- Pattachitra Painting Revives Tradition in Modern Art – Sarayu Australia, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://sarayu.com.au/blogs/interesting-facts/pattachitra-painting-revives-tradition-in-modern-art

- www.kalantir.com, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.kalantir.com/blogs/art-is-us/pattachitra

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pattachitra#:~:text=Pattachitra%20is%20one%20of%20the,the%20performance%20of%20a%20song.

- The Hybridity of Pattachitra Katha Media The Folk-pop Art Narrative Tradition of Bengal, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://ajbmss.org/the-hybridity-of-pattachitra-katha-media-the-folk-pop-art-narrative-tradition-of-bengal/

- Patachitra: Bengal and East India’s performing art of social, religious …, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.financialexpress.com/life/lifestyle-patachitra-bengal-and-east-indias-performing-art-of-social-religious-stories-telling-through-songs-paintings-1738684/

- View of Art as Storyteller | Sanglap: Journal of Literary and Cultural …, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://sanglap-journal.in/index.php/sanglap/article/view/251/427

- journals.acspublisher.com, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://journals.acspublisher.com/index.php/pimrj/article/download/20669/17844/35009

- Ministry of Culture Govt. of India – CCRT, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://ccrtindia.gov.in/wp-content/fellowship_research_project/AdaptionofPanchitratoSuitContemporarySociety.pdf

- Exploring the Significance of Pattachitra Art in Jagannath Ratha Yatra – Cottage9, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.cottage9.com/blog/exploring-the-significance-of-pattachitra-art-in-jagannath-ratha-yatra/

- Pattachitra Art: An Expression Of Mythology And Folklore – Cottage9, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.cottage9.com/blog/pattachitra-art-an-expression-of-mythology-and-folklore/

- Different styles of Pattachitra Artwork – MeMeraki, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.memeraki.com/blogs/posts/pattachitra-a-journey-through-four-artistic-traditions

- www.jetir.org, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.jetir.org/papers/JETIR2403195.pdf

- How Pattachitra Art Is Made: Step-by-Step Guide to Painting Techniques – Alokya, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://alokya.com/blogs/news/how-pattachitra-art-is-made-step-by-step-guide-to-painting-techniques

- Pattachitra: Where paintings tell a story | CJP – Citizens for Justice and Peace, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://cjp.org.in/pattachitra-where-paintings-tell-a-story/

- Pata paintings | Odisha State Museum, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://odishamuseum.nic.in/?q=node/97

- The Heritage and Evolution of Pattachitra Paintings – Exotic India Art, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.exoticindiaart.com/blog/the-heritage-of-pattachitra-paintings/

- A date with a sixth-generation pattachitra artist from Raghurajpur – Village Square, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.villagesquare.in/a-date-with-a-sixth-generation-pattachitra-artist-from-raghurajpur/

- Rich Heritage and Journey of Indian Pattachitra Paintings – Shantala Palat, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.shantalapalat.com/single-post/rich-heritage-indian-pattachitra-paintings

- Wholesale Pattachitra Paintings – Customization, Sustainability, And Profitability, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://ruralhandmade.com/blog/wholesale-pattachitra-paintings-customization

- BENGAL PATACHITRA – Ojas Art Gallery, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://ojasart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Satrangi-2018-Patachitra-Catalog.pdf

- Patachitra: storytelling in scroll and song – People’s Archive of Rural India, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.ruralindiaonline.org/hi/articles/patachitra-storytelling-in-scroll-and-song/

- How a Bengal Muslim Village Keeps Ancient Patachitra Art Alive …, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://frontline.thehindu.com/arts-and-culture/patachitra-artists-west-bengal-naya-paschim-medinipur-patuas-ancient-tradition-scroll-painting-song-dance/article69175244.ece

- Patachitra, India – ICH NGO Forum, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.ichngoforum.org/experience-on-the-ground/patachitra/

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pattachitra#:~:text=Bengal%20Patua%20artists%20carry%20the,Tagar%2C%20Mamoni%20and%20Laila%20Chitrakar.

- Patachitra-A Micro Scale Industry: Overview and Challenges – IOSR Journal, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jbm/papers/Vol20-issue3/Version-12/D2003122429.pdf

- Re-evaluating the Changing Tune of Scroll Paintings in Bengal – Patachitra Artform – New Delhi Publishers, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://ndpublisher.in/admin/issues/IJSSv7n4l.pdf

- Raksh Folk Arts Of India Foundation, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://indianfolkart.org/about-us/

- Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage – Wikipedia, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_National_Trust_for_Art_and_Cultural_Heritage

- Geographical Indication (GI) Tags: Protecting and Promoting Cultural Heritage through Products – TinkerChild, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.tinkerchild.com/post/geographical-indication-gi-tags-protecting-and-promoting-cultural-heritage-through-products

- CULTURAL TREASURES AS ECONOMIC ASSETS: HARNESSING THE GLOBAL POTENTIAL OF ODISHA’S GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS Sambhabi Patnaik, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.nlunagpur.ac.in/PDF/Publications/CI-Dec-2023/8.Shambhabi%20and%20Amrit.pdf

- Socio-economic Implications of Protecting Geographical Indications in India – Centre for WTO Studies, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://wtocentre.iift.ac.in/papers/Gi_Paper_CWS_August%2009_Revised.pdf

- Reviving Tradition: Patachitra Paintings from Sunderbans – Visions Art, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.visionsarts.com/patachitra-art-exhibition/

- Pattachitra Painting: The Timeless Folk Art of Odisha & Bengal, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://www.memeraki.com/collections/pattachitra

- Kalighat Painting – The Folk Art from Bengal l iTokri आई.टोकरी, accessed on May 22, 2025, https://itokri.com/blogs/craft-masala-by-itokri/kalighat-painting-the-folk-art-from-bengal