The Vibrant Art of Kolkata’s Temple Steps

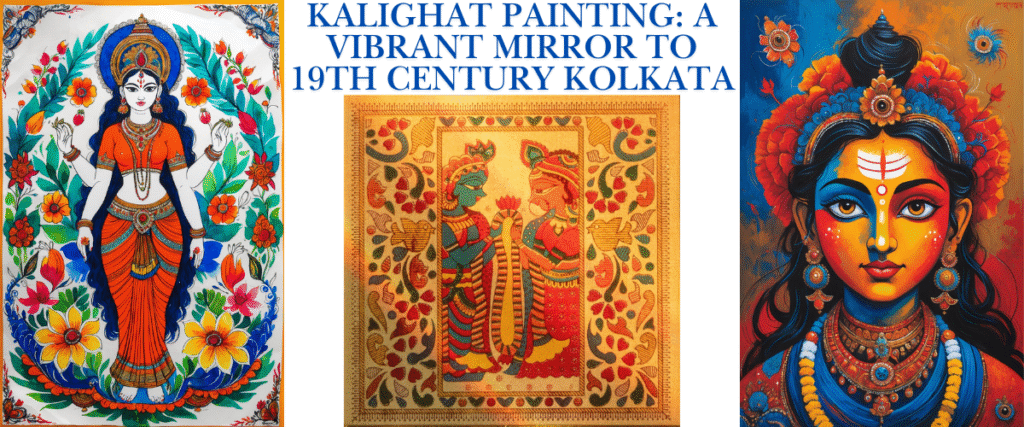

Amidst the bustling energy of 19th-century Kolkata (formerly Calcutta), a unique and influential style of Indian folk art emerged from the vicinity of the famed Kalighat Kali Temple.1 Known as Kalighat painting, or Kalighat Patachitra, this art form quickly captured the imagination of locals, pilgrims, and even foreign visitors.2 It stands out for its distinctive visual language: bold, sweeping outlines executed with masterful brushstrokes, vibrant watercolour pigments applied on paper, and strikingly minimal backgrounds that make the central figures pop.1 The subjects depicted were as diverse as the city itself, ranging from revered Hindu gods and goddesses and scenes from ancient epics to sharp social satire, depictions of everyday life, and commentary on contemporary events.2

Kalighat painting holds a significant place in the history of Indian art, considered by some scholars as perhaps the first truly modern and popular school of painting in India.1 Its surprising affinity with modern art, evident in its bold simplifications and visual rhythm, underscores its innovative nature.1 More than just decorative items, these paintings served as a vivid record of a society undergoing rapid transformation during the 19th and early 20th centuries, reflecting the cultural ferment of colonial Calcutta.2 This article delves into the fascinating world of Kalighat painting, exploring its origins with the traditional patua artists, its characteristic style and techniques, the rich tapestry of its themes, the factors leading to its eventual decline, and its enduring legacy in the landscape of Indian art.

Kalighat Painting at a Glance

To provide a quick overview, the table below summarises the key features of this captivating art form:

| Feature | Description |

| Origin | Kalighat area, Kolkata (Calcutta), West Bengal 1 |

| Period | Primarily 19th Century (c. 1830s – 1930s), peak mid-1870s 1 |

| Artists | Patuas (traditional scroll painters from rural Bengal) 1 |

| Style | Bold outlines, vibrant watercolours, minimal/plain backgrounds, expressive figures (elongated eyes, shading for volume) 1 |

| Themes | Religious (Hindu deities/epics), Social Satire (Babu culture, hypocrisy, Elokeshi case), Everyday Life, Contemporary Events, Animals 2 |

| Materials | Watercolour on paper (initially handmade, later mill-made), natural & chemical pigments 1 |

| Decline Factors | Rise of printing technology (lithography, oleographs), photography, changing tastes 4 |

| Legacy | Influence on Modern Indian Art (e.g., Jamini Roy), museum collections worldwide (V&A, Penn Museum, ROM, etc.), contemporary revival 4 |

From Village Storytellers to City Artisans: The Genesis of Kalighat Painting

The story of Kalighat painting begins not in the city, but in the villages of rural Bengal. For centuries, travelling folk painters known as patuas or chitrakars journeyed from village to village, carrying long scrolls painted on cloth or handmade paper, called patachitra.1 These scrolls depicted narrative stories, often drawn from Hindu epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata, or local folklore and religious tales.5 The patuas were more than just painters; they were performers, unrolling the scrolls section by section while singing or reciting the corresponding story, captivating village audiences and serving as keepers of cultural and religious narratives.5 Their art was intimately tied to this performative, community-based tradition.

The 19th century, however, brought significant changes. Calcutta, under British administration, rapidly transformed into a major economic, administrative, and cultural centre, attracting migrants from across the region seeking work and opportunity.3 Central to this bustling metropolis was the Kalighat Kali Temple. According to legend, the site became sacred when a toe from the goddess Sati’s body fell there, making it an important pilgrimage destination.13 Rebuilt or established in its current form likely in the early 19th century, the temple drew vast crowds of devotees, curious locals, and even European visitors daily.1 This constant flow of people created a fertile ground for commerce. Sensing opportunity, artisans and craftspeople from surrounding rural districts like 24 Parganas, Midnapore, and Murshidabad, including many skilled patuas, migrated to the city and set up shop near the temple.3

This migration marked a pivotal moment. The urban environment of Kalighat presented a different audience with different demands compared to the villages. Pilgrims and tourists desired mementos of their visit – something easily portable, affordable, and representative of the holy site.2 The traditional patachitra scrolls, often twenty feet long, were costly, cumbersome, and ill-suited for this new market; the traditional storytelling performance was also impractical in the crowded temple lanes.7 Faced with these new realities and driven by economic necessity, the patuas adapted. They transitioned from the long narrative scrolls to creating single-sheet paintings, known as pats, typically on paper.2 This shift, occurring roughly between the 1830s and 1850s, marked the birth of the Kalighat painting style.1

This transition signifies more than just an artistic evolution; it reflects a fundamental change in the patuas’ socio-economic role. They moved from being itinerant performers embedded in rural community life, often relying on patronage or donations, to becoming urban artisans and vendors operating within a commercial, cash-based economy.6 This transformation necessitated a different approach to art-making, prioritising speed, efficiency, and subjects with broad appeal to a diverse, transient audience. The very emergence of Kalighat painting thus exemplifies how urbanisation can act as a powerful catalyst, forcing traditional folk art forms to adapt and evolve in response to new social dynamics, market pressures, and the unique environment of the city.2 The city wasn’t merely a backdrop; it actively shaped the form, function, and identity of this new art.

Defining the Kalighat Style: Techniques and Materials

The Kalighat style is immediately recognisable for its visual directness and energy. Its most defining characteristics include strong, bold, and fluid lines, often drawn with remarkable confidence in a single, continuous sweep of the brush.1 Ajit Ghose, an early commentator, noted that in these lines, “not the faintest suspicion of even a momentary indecision, not the slightest tremor, can be detected”.1 These decisive outlines define figures rendered in vibrant, flat, and opaque watercolours, which stand out dramatically against minimal or entirely plain backgrounds, devoid of unnecessary detail.1

The artist skillfully used specific features to convey emotion and vitality. Oversized, expressive, elongated, almond-shaped eyes are a hallmark, lending the figures a sense of drama and life.5 Hands are often depicted with care, contributing to the narrative gesture.5 While colours are generally flat, the patuas employed a distinctive form of shading – broad strokes of deep colour often fading into lighter washes – to give a sense of volume and roundness to limbs and faces, creating a subtle three-dimensionality that contrasts effectively with the flat surroundings.6

The materials used reflect the artists’ adaptation to the urban environment and market demands. While early works might have occasionally used cloth or handmade paper, the vast majority of Kalighat paintings were executed on inexpensive, readily available mill-made paper, often imported from Britain.1 Some sources suggest the paper surface was sometimes pre-treated with a thin coating of chalk or lime paste to create a smoother surface.5 Similarly, while the patuas initially would have used traditional pigments derived from natural sources – minerals, soot (for black), turmeric (for yellow), indigo or Aparajita flowers (for blue), leaves, and possibly beetroot (for red) – ground and mixed with gum arabic or other binders, they quickly adopted the cheaper, commercially produced European-style watercolours that became available in Calcutta.3 To add a touch of richness, especially for depicting jewellery or divine attributes, artists often used silver, gold, or colloidal tin highlights.8 Their tools remained simple: brushes typically fashioned from squirrel or goat hair.2

The production process itself was geared towards efficiency. Kalighat painting was frequently a collaborative effort, undertaken by family units or groups working in an assembly-line fashion.2 Tasks were divided: a master artist might sketch the initial outline in pencil, often copying from a model sketch; another member would handle the shading or modelling; others, sometimes women and children, would fill in the designated areas with specific colours (having perhaps ground the pigments earlier if using natural ones); finally, the defining outlines and finishing details would be added, usually in black.2 This system allowed for the rapid production of hundreds of paintings, essential for supplying the bustling souvenir market.10

The adoption of Western materials like mill paper and watercolours, along with techniques like shading, has sparked debate about the extent of Western influence on the Kalighat style. Scholars like W.G. Archer argued that these elements, combined with plain backgrounds and urban themes, indicated a direct borrowing from British art and prints circulating in Calcutta’s bazaars.6 However, many historians counter this view, asserting the style’s fundamental indigenous character.6 They argue that shading techniques could have derived from the patuas’ traditional practice of painting three-dimensional clay idols.6 The use of paper and watercolours is seen by many as a pragmatic choice for mass production rather than artistic imitation, noting that the opaque vibrancy of Kalighat colours differs from translucent British watercolours.6 Furthermore, plain backgrounds exist in earlier Indian manuscript traditions, and the patuas had limited direct interaction with British artistic circles.6 The frequent use of satire aimed at Westernised Bengalis or colonial figures also suggests a critical engagement rather than simple adoption.3 Ultimately, Kalighat painting appears to represent a dynamic synthesis – a “cosmopolitan folk culture” 2 – where artists selectively utilised available materials and responded to their urban environment while retaining a distinctly Indian aesthetic, rooted in their own traditions but adapted for a new era. The choice of materials seems driven more by pragmatism – the need for speed and affordability in a competitive market – than by a desire to emulate foreign styles.3 This economic reality, in turn, likely influenced the very development of the style; the bold lines, flat colours, and streamlined production process were not just aesthetic choices but functional necessities for survival in the bazaar.1

A Mirror to Nineteenth-Century Bengal: Themes and Subjects

The thematic range of Kalighat painting is remarkably broad, reflecting the diverse stimuli of 19th-century Calcutta – from the sacred precincts of the temple to the rapidly changing social landscape outside its walls.

Initially, and throughout the tradition’s existence, religious subjects remained paramount, catering directly to the pilgrims who formed the core market.2 The Hindu pantheon was vividly brought to life: Kali, the presiding deity of the temple, was a central figure, often depicted in her fierce forms.11 Other popular deities included Durga (especially slaying the buffalo demon Mahishasura), Lakshmi, Saraswati, Shiva (often with Parvati and Ganesha), Krishna (in various lilas – with Radha, the gopis, his mother Yashoda, or brother Balaram), Rama and Sita, Hanuman, and Kartikeya.2 Scenes from the great epics, the Ramayana and Mahabharata, were common subjects.2 These religious works are sometimes categorised as belonging to the ‘Oriental School’ of Kalighat painting.3 Demonstrating their adaptability, artists also occasionally depicted figures from other faiths, such as Islamic prophets, angels, taziyas (tomb models carried in Muharram processions), or Duldul (Imam Hussain’s horse), likely catering to a wider clientele.7 A particularly interesting aspect was the ‘Bazaar Style’, where even gods and goddesses were sometimes portrayed in contemporary settings or attire, blurring the line between the divine and the everyday – Shiva might appear as an ordinary father, Kartikeya as a fashionable dandy, or deities might sport Western shoes or hold violins.3

As the patuas settled into urban life, their gaze turned outward, and they began to document and comment on the society around them, leading to the ‘Occidental School’ of secular themes.3 Social satire became a powerful vein within Kalighat art.5 A prime target was the ‘Babu culture’ – the newly affluent, Western-educated Bengali middle class.3 Paintings humorously mocked the Babus’ adoption of European fashions (like the ‘Albert’ hairstyle, buckled shoes, elaborate shawls) and manners, their perceived idleness (lounging on Victorian chairs, smoking hookahs), and sometimes their moral failings, such as associations with courtesans.3 Religious hypocrisy was another recurring theme, famously symbolised by the image of a cat (often with Vaishnavite markings) stealing a fish or prawn, representing outwardly pious figures (like priests or Babus) indulging in forbidden or deceitful behaviour.2 Critiques could also be aimed at corrupt temple priests or the impact of colonialism itself, sometimes subtly depicting British officials or mocking the effects of their rule.4 One striking example interprets the traditional image of Durga slaying Mahishasura as a subversive commentary, depicting the demon wearing British-style buckled shoes, thus casting him as a symbol of colonial power being vanquished.11

Beyond satire, Kalighat paintings served as chronicles of their time, capturing scenes from everyday life and sensational events.2 Artists depicted the bustling life of Kolkata: women engaged in household chores or adorning themselves, musicians, barbers attending to clients, courtesans (bibis), fish sellers, men riding elephants, people interacting with domestic pets like cats and birds.2 The patuas’ stalls effectively became visual “news bureaus” 15, documenting contemporary happenings, including crimes and scandals that gripped the city’s imagination.3 The most famous instance is the Tarakeswar affair of 1873. This scandal involved the illicit relationship between Elokeshi, the young wife of Nabinchandra Banerjee, and the head priest (Mahant) of the Tarakeswar Shiva temple, culminating in Elokeshi’s brutal murder by her husband. The Kalighat artists produced a series of paintings narrating the entire saga – the seduction, the affair (or implied rape), the murder, and the subsequent trial of both the husband and the Mahant – reflecting and likely fueling public fascination with the case.6 In a different vein, depictions of historical figures associated with resistance against British rule, such as Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi or Tipu Sultan, also appeared, suggesting the art form played a role in circulating nationalist sentiments.3

Women were frequent subjects, portrayed in a multitude of roles: as powerful goddesses, devoted wives and mothers (like Yashoda), elegant courtesans, romantic heroines (nayikas, such as the ‘Lady with a Peacock’symbolising longing for an absent lover), tragic figures like Elokeshi, or symbols of national pride like Rani Lakshmibai.2 Images often focused on feminine activities like applying kohl or tending to household tasks, sometimes incorporating the bonti (a traditional curved blade for cutting vegetables), which became strongly associated with Bengali women.2 Some scholars note the potential intersection of these depictions with colonial sensibilities and the male gaze, where eroticism might be subtly woven into religious or everyday scenes.24

The sheer breadth of these themes reveals that Kalighat painting functioned as far more than just religious souvenir art. It evolved into a dynamic medium for social commentary, critique, and even a form of visual journalism, capturing the pulse of 19th-century Calcutta.3 The patuas became keen observers and visual chroniclers of their rapidly changing urban world, using their accessible art form to reflect, interpret, and disseminate information and opinion on everything from religious beliefs to social scandals and political undercurrents. Furthermore, the constant blending of the sacred and the secular, the traditional Indian aesthetic with elements adopted from the colonial environment (even if only materials), and the multiple functions of the art – devotional, decorative, satirical, narrative – highlight hybridity as a core characteristic.2 Kalighat painting is thus a quintessential product of its time and place, embodying the complex cultural negotiations occurring in colonial Calcutta.

The Fading of a Folk Art: Decline in the Machine Age

Despite its vibrancy and popularity throughout much of the 19th century, the tradition of hand-painted Kalighat pats began to wane towards the end of the century and declined significantly in the early decades of the 20th century.4 The primary catalyst for this decline was the advent and proliferation of new, cheaper methods of mass image production.4

Mechanical printing technologies, including woodcut, lithography (often hand-coloured to mimic paintings), and later oleography, began to flood the market.4 Printing presses sprang up in Calcutta and Bombay, and prints were also imported from Europe, particularly Germany.4 These machine-made images could reproduce visuals, including religious icons and even direct imitations of Kalighat paintings, at a fraction of the cost and in much larger quantities than the hand-painted pats.6 Although Kalighat paintings were already inexpensive, selling for perhaps just two to four pice each, they simply could not compete economically with the efficiency of the printing press.6 Alongside printing, the growing popularity and accessibility of photography offered another novel and increasingly affordable way to capture and disseminate images, further challenging the dominance of traditional hand-painted forms.4

This influx of cheap, mass-produced prints and photographs fundamentally altered the market for popular imagery. Consumers, attracted by the lower prices and perhaps the novelty or perceived realism of the new technologies, shifted their preferences away from the hand-painted pats.4 The demand for Kalighat paintings dwindled. The decline began to be felt from the late 1880s onwards, and by the 1930s, the tradition in its original form had largely died out, with the last known practitioners passing away or abandoning the craft.2 Subsequent generations of patua families were forced to seek alternative livelihoods, often leaving the city.6

In retrospect, the decline of Kalighat painting illustrates a poignant dynamic. The very factors that fueled its rise – its adaptation for mass consumption, its simplified style facilitating quick reproduction, its commodification as an affordable souvenir – paradoxically made it susceptible to being superseded by even more efficient modes of mass production.4 By successfully becoming a popular commodity, it inadvertently paved the way for its own obsolescence when technologically superior commodities entered the same market space. The story of Kalighat’s decline serves as an early and compelling case study of technological disruption impacting traditional arts. It demonstrates how innovations like mass printing and photography could rapidly displace long-standing, handcrafted traditions, especially those operating within the sphere of popular, commercial visual culture, a pattern that would repeat itself across various crafts and regions with the advance of industrialisation.4

Enduring Echoes: The Legacy of Kalighat Painting

Though the bustling production of Kalighat paintings for the pilgrim market faded by the early 20th century, the art form left an indelible mark on Indian art history and continues to resonate today. Its legacy unfolds in several significant ways.

One of the most crucial aspects of its legacy is its influence on the development of Modern Indian Art.6 In the early 20th century, as Indian artists sought to forge an artistic identity distinct from the Western academic styles promoted by British-run art schools, they turned to indigenous traditions for inspiration.6 Kalighat painting, with its bold linearity, vibrant flat colours, simplified forms, and expressive power, offered a compelling model of an authentically Indian visual language that was both traditional and strikingly modern.1 The most celebrated example is the renowned painter Jamini Roy, who consciously rejected his academic training and drew heavily from the Kalighat style, adopting its strong outlines, earthy palette, and figural simplicity to create his iconic works.6 The satirical Kalighat pats also inspired the caricatures of Gaganendranath Tagore, another key figure in early modern Indian art, who used a similar spirit to lampoon the Bengali elite.18

Furthermore, the Kalighat tradition did not vanish entirely. While the original urban phenomenon declined, the style and techniques have been kept alive and adapted by contemporary artists, many of whom belong to the patua community and reside in the rural districts of West Bengal.4 Artists like Kalam Patua, Anwar Chitrakar, Bhaskar Chitrakar, Uttam Chitrakar, Bapi Chitrakar, and Hasir Chitrakar continue to practice and evolve the form.23 These contemporary practitioners often work with traditional themes, depicting gods and goddesses, but they also apply the distinctive Kalighat style to modern subjects, social commentary, and current events, sometimes returning to the use of organic dyes.4 Kalam Patua, for instance, has created a series depicting life in a post office (drawing on his own profession), figures using smartphones, or responding to contemporary social issues, demonstrating the style’s enduring capacity for relevance.23 This continued practice underscores a key aspect of the Kalighat legacy: its inherent adaptability. The same spirit that allowed 19th-century patuas to transform scroll painting into bazaar art enables contemporary artists to use the Kalighat visual language to engage with the present day.4

Perhaps the most visible testament to Kalighat painting’s significance today is its presence in major museums and collections across the globe.1 What began as cheap, ephemeral souvenirs, often disregarded by local elites as unworthy of serious artistic consideration 19, underwent a remarkable transformation in status. Collected initially by European travellers like Maxwell Sommerville or administrators like John Lockwood Kipling (whose collection was later gifted by his son, Rudyard Kipling), these paintings eventually found their way into institutional collections.2 Over time, art historians and curators recognised their unique aesthetic qualities and immense socio-historical value as documents of a specific time and place.1 Today, significant collections are housed in institutions such as the Victoria & Albert Museum in London (holding the world’s largest collection) 1, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Penn Museum) 7, the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) 10, the Cleveland Museum of Art 11, the Gurusaday Museum in Kolkata 23, the Naprstek Museum in Prague 17, the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi 23, and many others.19 This journey from bazaar to museum highlights a profound re-evaluation of folk and popular art within the broader narrative of art history, acknowledging its cultural importance and aesthetic merit. The style also finds echoes in contemporary design, with Kalighat motifs appearing on textiles and other products.4

Conclusion: The Timeless Appeal of Kalighat Art

The story of Kalighat painting is a compelling narrative of adaptation, innovation, and cultural reflection. Born from the convergence of rural artistic tradition and the dynamic urban environment of 19th-century Kolkata, it saw traditional patua scroll painters transform themselves into creators of a new, vibrant form of popular art. Characterised by its bold lines, vivid colours, and expressive simplicity, the Kalighat style proved remarkably versatile, adept at depicting both the divine figures sought by pilgrims and the complex social realities unfolding outside the temple walls.

These paintings served as more than just souvenirs; they were a mirror held up to a society in flux, capturing the emergence of new social classes like the Babus, commenting on shifting moral landscapes through scandals like the Elokeshi affair, and offering satirical critiques of hypocrisy and colonial influence. Its eventual decline in the face of mass-produced prints underscores the impact of technology on traditional crafts, yet its legacy endured. Kalighat painting provided crucial inspiration for modern Indian artists seeking an indigenous aesthetic, and its visual language continues to be practised and adapted by contemporary patuas.

Today, preserved in museums worldwide, Kalighat paintings offer invaluable insights into the social, cultural, and artistic life of 19th-century Bengal. Their journey from ephemeral bazaar art to treasured cultural artifacts speaks volumes about their enduring significance. The timeless appeal of Kalighat art lies in its unique blend of folk simplicity and surprising sophistication, its directness of expression, and its insightful, often witty, commentary on the human condition, securing its vital place in the rich tapestry of Indian art history.1

Disclaimer

This article synthesises information from various historical accounts, scholarly interpretations, and museum records concerning Kalighat painting. While compiled with attention to accuracy based on the available research, interpretations of art history and the specific details surrounding the origins, evolution, and decline of Kalighat painting may vary among experts and are subject to ongoing research and discussion.

Reference

- Kalighat Paintings: A review, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://www.chitrolekha.com/V3/n1/02_Kalighat_Paintings.pdf

- Kalighat painting – Wikipedia, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kalighat_painting

- Rooftop Blog: The Evolution of Kalighat Painting: History, Themes …, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://rooftopapp.com/blogs/the-evolution-of-kalighat-painting-history-themes-

- Rooftop Blog: Kalighat Paintings: The Folk Art That Defines Kolkata, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://rooftopapp.com/blogs/kalighat-paintings-the-folk-art-that-defines-kolkata-1

- Kalighat Paintings: Top 5 Bengal’s Unique Contribution to Art – Folk Canvas, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://folkcanvas.com/east-india/west-bengal/kalighat-painting-bengal-art/

- The Rise and Fall of Kalighat Paintings | Sahapedia, accessed on May 2, 2025, http://www.sahapedia.org/rise-and-fall-kalighat-paintings

- Kalighat Painting – MAP Academy, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://mapacademy.io/article/kalighat-painting/

- Kalighat Painting – The Folk Art from Bengal l iTokri आई.टोकरी, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://itokri.com/blogs/craft-masala-by-itokri/kalighat-painting-the-folk-art-from-bengal

- Kalighat Paintings – MeMeraki, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://www.memeraki.com/blogs/posts/kalighat-paintings

- Kalighat Paintings: Murder in the Collection | Royal Ontario Museum, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://www.rom.on.ca/media-centre/blog-post/kalighat-paintings-murder-collection

- Indian Kalighat Paintings | Cleveland Museum of Art, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://www.clevelandart.org/articles/indian-kalighat-paintings

- Kalighat Paintings – The History, Themes, And Styles – eCraftIndia, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://www.ecraftindia.com/blogs/articles/kalighat-paintings-the-history-themes-and-styles

- Kalighat painting · V&A, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/kalighat-painting

- Kalighat Painting, Features, Techniques, UPSC Notes – Vajiram & Ravi, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://vajiramandravi.com/quest-upsc-notes/kalighat-painting/

- The Sampradaya Sun – Independent Vaisnava News – Feature Stories – October 2005, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://www.harekrsna.com/sun/features/10-05/features104.htm

- The Lady with a Peacock: The Story of Kalighat Paintings – HASTA Magazine, accessed on May 2, 2025, http://www.hasta-standrews.com/features/2018/4/18/the-lady-with-a-peacock-the-story-of-kalighat-paintings

- Kalighat Painting – Children’s Art Museum of India, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://www.childrensartmuseumofindia.com/post/kalighat-painting

- Kalighat Pats – DAG, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://dagworld.com/kalighat-pats.html

- Kalighat Icons – Paintings from 19th century Calcutta – National Museum Wales, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://museum.wales/articles/2007-04-02/Kalighat-Icons—Paintings-from-19th-century-Calcutta/

- Kalighat Paintings from Nineteenth Century Calcutta in Maxwell Sommerville’s ‘Ethnological East Indian Collection’ – Penn Museum, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/kalighat-paintings-from-nineteenth-century-calcutta-in-maxwell-sommervilles-ethnological-east-indian-collection/

- Kalighat Painting Style – Umaid.art, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://umaid.art/2022/08/12/kalighat-painting-style/

- Kalighat.pdf – Penn Museum, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://www.penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/42-3/Kalighat.pdf

- Kalam Patua – :::::: Daricha Foundation ::::::, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://daricha.org/artists_details.aspx?ArtistID=44QZBJI2APHN

- How Bengal’s Nineteenth-Century Art Defined Women – JSTOR Daily, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://daily.jstor.org/how-bengals-nineteenth-century-art-defined-women/

- Kalam Patua’s Kalighat Paintings Chronicle The Sociological Evolution of Urban India, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://homegrown.co.in/homegrown-creators/art-design/kalam-patuas-kalighat-paintings-chronicle-the-sociological-evolution-of-urban-india

- Kalighat Paintings and Art Collection – MeMeraki, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://www.memeraki.com/collections/kalighat

- APT8: Kalam Patua’s contemporary storytelling, accessed on May 2, 2025, https://www.qagoma.qld.gov.au/stories/apt8-kalam-patuas-contemporary-storytelling