The Shock of the New

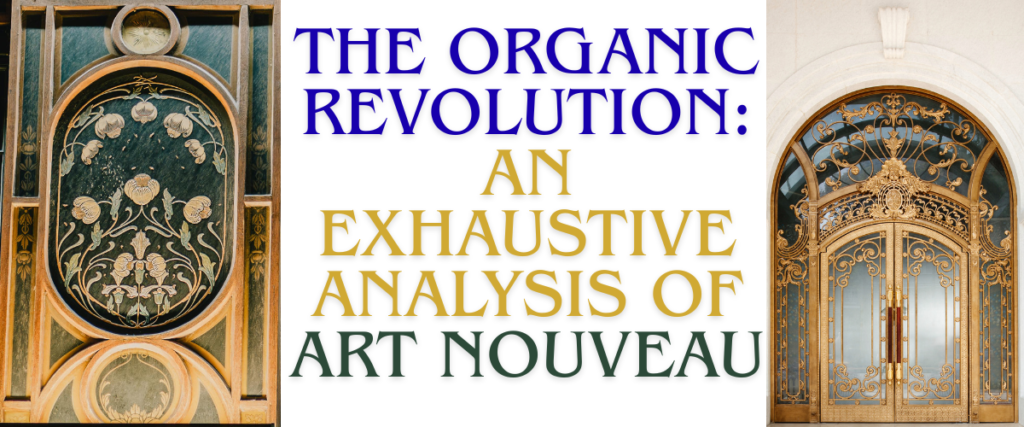

In the waning years of the nineteenth century, Western civilisation stood at a precipice. The Industrial Revolution had irrevocably altered the landscape of daily life, shrouding cities in the soot of progress and flooding markets with mass-produced commodities that many critics found soulless and devoid of character. The rigid academicism of the Victorian era, with its incessant recycling of historical styles—Neo-Classical, Neo-Gothic, Neo-Renaissance—felt increasingly exhausted, a tired echo of the past rather than a voice for the future.1 It was in this climate of aesthetic fatigue and social upheaval that Art Nouveau exploded onto the scene.

Emerging roughly between 1890 and 1910, Art Nouveau (literally “New Art”) was not merely a decorative trend; it was a radical philosophical movement that sought to heal the rift between the fine and applied arts, to democratize beauty, and to reintegrate the rhythms of nature into the increasingly mechanised human experience.2 From the wrought-iron tendrils of a Paris Métro station to the iridescent sheen of a Tiffany lamp, the movement represented a “passionate urge” to revolutionise design by stripping away the heavy drapes of historicism and replacing them with a vocabulary derived entirely from the organic world.1

This report offers a comprehensive examination of Art Nouveau, exploring its complex origins, its pan-European and transatlantic manifestations, its philosophical underpinnings, and its enduring legacy. We will traverse the sinuous curves of Belgian architecture, the geometric rigour of the Vienna Secession, the ethereal lithographs of Alphonse Mucha, and the hidden contributions of female artisans like Clara Driscoll. By dissecting the movement’s successes and its inherent paradoxes—specifically the tension between its socialist ideals and its elitist price tags—we gain insight into the first truly international style of the modern age.1

The Genesis of a Movement: Historical and Philosophical Roots

To understand the flowering of Art Nouveau, one must first understand the soil from which it grew. The movement did not arise in a vacuum; it was a synthesis of several cultural currents that had been gaining momentum throughout the late 19th century.

The Reaction Against Industrialization: Arts and Crafts

The primary intellectual progenitor of Art Nouveau was the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain, spearheaded by the theoretical writings of John Ruskin and the practical craftsmanship of William Morris.1 Ruskin and Morris were fierce critics of industrial capitalism, arguing that the division of labour in factories degraded the worker and produced ugly, shoddy goods. They advocated for a return to the medieval guild system, where the designer and the maker were one and the same, and where “joy in labour” could be reclaimed.2

Art Nouveau absorbed this reverence for craftsmanship and the belief that the home should be a “total work of art” (Gesamtkunstwerk), where every object, from the wallpaper to the cutlery, contributed to a unified aesthetic harmony.6 However, while Morris looked backward to the Gothic past and largely rejected the machine, Art Nouveau designers took a more nuanced approach. In France and Belgium, particularly, architects like Hector Guimard and Victor Horta embraced modern industrial materials—iron and glass—but sought to bend them to the will of the artist, transforming cold metal into organic, living forms.6

The Aesthetic Movement and “Art for Art’s Sake”

Running parallel to Arts and Crafts was Aestheticism, a movement that rejected the Victorian notion that art must serve a moral or didactic purpose. Led by figures like Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley, the Aesthetes championed the slogan “art for art’s sake”.1 They believed that beauty was a supreme value in itself and that life should be lived as a work of art.

This philosophy deeply permeated Art Nouveau, particularly in its more decadent and erotic manifestations. The movement’s obsession with beauty—sometimes bordering on the perverse or the darker aspects of nature (decay, wilting flowers, femmes fatales)—can be traced directly to the Aesthetes’ rebellion against Victorian prudery.7

The Eastward Gaze: Japonisme

Perhaps the most crucial visual catalyst for Art Nouveau was the opening of trade with Japan in the mid-19th century. The sudden influx of Japanese ceramics, textiles, and ukiyo-e woodblock prints by masters like Hokusai and Hiroshige created a frenzy in European artistic circles known as Japonisme.8

European artists, accustomed to the rigid rules of Renaissance perspective and symmetry, were electrified by the Japanese approach to composition. They saw:

- Asymmetry: A reverence for the irregular and the balanced rather than the mirrored.

- Flatness: The use of bold, flat areas of colour and strong contour lines, rejecting the illusion of three-dimensional depth.

- Nature as Motif: The depiction of flora and fauna not as static scientific specimens, but as dynamic, living entities.1

These elements became foundational to the Art Nouveau grammar. The “whiplash” curve, the cropping of images, and the stylised rendering of plants were all direct borrowings from the “floating world” of Japanese art.10

The Birth of the Name

The crystallisation of these disparate influences into a coherent style occurred in the mid-1890s. The term “Art Nouveau” itself was popularised by Siegfried Bing, a German-born art dealer in Paris. In December 1895, Bing opened a gallery called Maison de l’Art Nouveau (House of New Art) on the Rue de Provence.1 He exhibited a curated collection of modern glass (by Tiffany and Gallé), jewellery (by Lalique), and paintings that defied categorisation.

Although the press initially used the term “Art Nouveau” mockingly, it stuck. It became the banner for a movement that, despite its many regional names, shared a singular ambition: to create a style that owed nothing to the past and everything to the present and future.2

The Grammar of the Style: Defining Characteristics

Art Nouveau is visually distinct, arguably the most recognisable style in art history. It is characterised by a specific set of visual codes that transcend the medium, whether applied to a stone facade or a diamond brooch.

The Line of Beauty: The “Whiplash”

The single most iconic element of Art Nouveau is the whiplash line (coup de fouet). This is a dynamic, undulating curve that snaps back on itself, mimicking the energy of a cracking whip or the tendril of a climbing plant seeking purchase.1 Unlike the static circle or the rigid straight line, the whiplash is active; it implies movement, growth, and tension.

This line appeared everywhere:

- Architecture: Iron balustrades that seemed to grow out of stone floors.

- Graphic Design: Hair that swirled around a woman’s body like water currents.

- Furniture: Table legs that bowed and stretched like animal limbs.

The whiplash was not merely decorative; it was structural. In the hands of architects like Horta, the line dictated the very form of the building, dissolving the boundary between structure and ornament.1

Biomorphism and Organic Logic

Art Nouveau’s obsession with nature went beyond mere representation. Artists did not just paint flowers; they studied the logic of plant growth. They looked at how a stem thickens to support a bud, how a leaf unfurls, how seaweed drifts in the tide.1

- Flora: The movement favoured “unconventional” plants with sinuous forms: lilies, irises, orchids, poppies, and thistles.

- Fauna: Creatures with iridescent or delicate structures were preferred: dragonflies, peacocks, swans, and snakes.1

This biomorphic approach meant that objects were designed to look as if they had grown rather than been built. A chair was not a collection of joined wood; it was a living organism frozen in time.

The Femme-Fleur: Gender and Symbolism

The human figure, specifically the female form, was central to Art Nouveau imagery. The “Art Nouveau Woman” was a distinct archetype: the Femme-Fleur (Flower Woman). She was often depicted with flowing, pre-Raphaelite hair that merged with the surrounding vegetal decoration, symbolising humanity’s connection to nature.14

However, this representation was dualistic. She could be the ethereal, virginal muse of Alphonse Mucha, representing beauty and allegory. Alternatively, she could be the dangerous Femme Fatale of Aubrey Beardsley or Gustav Klimt—a symbol of the terrifying, untamable power of nature and sexuality.7 This focus on the female form reflected the era’s complex psychological relationship with women’s changing roles in society.

Integration of Structure and Decor

A key tenet of Art Nouveau was the rejection of “applied” ornament. In traditional Victorian design, a structure would be built and then decorated. In Art Nouveau, the structure was the decoration. A table leg didn’t just have a flower carved on it; the leg was the stalk of the flower.1 This unity of the arts was a radical departure from the eclectic historicism that preceded it.

A Polyglot Style: Regional Variations and Nomenclature

Art Nouveau was a truly international phenomenon, erupting simultaneously across Europe and the Americas. Interestingly, because it emphasised a break from tradition, it took on different names and slightly different visual characteristics in each country. It was a language with many dialects.1

France and Belgium: The Curvilinear Heartland

In the Francophone world, the style was most closely associated with the flowing, floral, and “whiplash” aesthetic.

- Belgium: Often cited as the birthplace of Art Nouveau architecture, thanks to Victor Horta and Paul Hankar. Horta’s Hôtel Tassel (1893) is widely considered the first Art Nouveau building, famous for its open plan and the seamless integration of ironwork into the interior decor.6

- France: The style flourished in Paris and Nancy. In Paris, it was often called Style Métro after Hector Guimard’s famous cast-iron subway entrances, which transformed the descent into the underground into a walk through a fantastical garden.1 Detractors mocked it as Style Nouille (Noodle Style) due to its writhing forms.1 The École de Nancy, led by Émile Gallé, focused heavily on botany and the decorative arts.17

Germany and Austria: The Geometric Turn

In German-speaking countries, the style evolved from floral origins into something more geometric and abstract, paving the way for Modernism.

- Germany: Known as Jugendstil (“Youth Style”) after the magazine Die Jugend.18 It began with floral motifs but quickly adopted “abstracted” natural forms.

- Austria: The Vienna Secession (Sezessionstil) was a formal breakaway from the conservative art establishment, led by Gustav Klimt. The Viennese style, influenced by Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, favoured clean lines, geometric patterns (like checkerboards), and a heavy use of gold, distinct from the sinuous curves of Paris.19

Britain and Scotland: The Linear North

While the Arts and Crafts movement started in England, the British manifestation of Art Nouveau was distinct.

- Scotland: The Glasgow Style, led by Charles Rennie Mackintosh and “The Four,” was unique for its verticality, rectilinear forms, and sparse, elegant decoration (the “Glasgow Rose”). It was a stark contrast to the lush excesses of the French style.21

- England: Often called the Modern Style, it was heavily influenced by the graphic work of Aubrey Beardsley and the retailer Liberty & Co. (hence the Italian name for the style, Stile Liberty).12

Spain: Modernisme and Gaudí

In Catalonia, the movement was known as Modernisme. While sharing the organic philosophy, it was deeply tied to Catalan nationalism and Catholic mysticism. It’s titan, Antoni Gaudí, created buildings that defied classification, using hyperbolic paraboloids and catenary arches to create structures that functioned like living organisms.12

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Regional Styles

| Region | Local Name | Key Figures | Visual Characteristics |

| France | Art Nouveau, Style Métro | Hector Guimard, Émile Gallé, René Lalique | Flowing, floral, whiplash curves, elegant, “femme-fleur”. |

| Belgium | Art Nouveau, Style Coup de Fouet | Victor Horta, Henry van de Velde | Structural ironwork, open plans, biological rhythms, light. |

| Austria | Sezessionstil (Vienna Secession) | Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann, Otto Wagner | Geometric, rectilinear, gold leaf, checkerboard patterns, abstract. |

| Germany | Jugendstil | Hermann Obrist, Peter Behrens | Mythological, influential on typography, evolving from floral to geometric. |

| Scotland | Glasgow Style | Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Margaret Macdonald | Vertical lines, elongated forms, rose motifs, high-backed chairs. |

| Spain | Modernisme | Antoni Gaudí, Lluís Domènech i Montaner | Hyper-organic, colourful mosaics (trencadís), religious symbolism, structural innovation. |

| USA | Tiffany Style | Louis Comfort Tiffany, Louis Sullivan | Iridescent glass, nature themes, intricate metalwork. |

| Italy | Stile Liberty, Stile Floreale | Pietro Fenoglio | Floral exuberance is often applied to more traditional building forms. |

The Art of Persuasion: Mucha and the Graphic Revolution

If Art Nouveau had a public face, it was the poster. The development of colour lithography in the late 19th century transformed the streets of Paris into “art galleries for the poor,” allowing artists to bring their aesthetic to the masses.14

Alphonse Mucha: The unintended Icon

The most famous practitioner of this genre was Alphonse Mucha, a Czech artist living in Paris. His rise to fame is the stuff of legend. In December 1894, the great actress Sarah Bernhardt needed a rush poster for her play Gismonda. Mucha, the only artist available, produced a design that shattered convention.24

- Verticality: He used a long, narrow format that emphasised Bernhardt’s height and elegance.

- Palette: Instead of the garish primary colours common in advertising, Mucha used soft pastels, gold, and earthy tones.

- Motifs: He framed Bernhardt in a Byzantine mosaic halo, dressing her in flowing robes that turned the actress into a secular saint.24

The poster was a sensation; Parisians reportedly stole them off the walls. This birthed Le Style Mucha, characterised by the “Q-formula” (a seated figure with a circular motif behind the head), spaghetti-like hair, and intricate botanical borders.14 Mucha’s work for clients like JOB cigarette papers and Moët & Chandon elevated the commercial advertisement to high art, embodying the movement’s goal of beautifying everyday life.

Aubrey Beardsley: The Dark Line

Across the channel, the English illustrator Aubrey Beardsley offered a darker, more provocative vision. His black-and-white ink drawings, famously for Oscar Wilde’s Salome, were stark, grotesque, and undeniably erotic. Influenced heavily by Japanese woodcuts and Greek vase painting, Beardsley used large areas of negative space and incredibly fine, hair-like lines. His work was controversial, often exploring themes of decay and sexuality that contrasted sharply with Mucha’s idealised beauty, showcasing the range of the Art Nouveau spectrum.7

Architecture and the Total Work of Art

Art Nouveau architects were not content to simply design a building’s shell; they sought to control the entire environment. The house was treated as a living organism, where the exterior facade, the interior layout, and the furnishings were inseparable.

Victor Horta and the Open Plan

In Brussels, Victor Horta radically altered domestic space. In the Hôtel Tassel (1893), he abandoned the traditional box-like rooms and dark corridors of the 19th-century townhouse. Instead, he opened the interior to light, using glass ceilings and iron columns that branched out like trees.16 The famous staircase of the Hôtel Tassel is a manifesto of the style: the iron balustrade curves down the stairs, its lines echoed in the mosaic floor and the painted wall decoration, creating a dizzying, immersive sense of movement.6

Antoni Gaudí: The Architect of God

In Barcelona, Antoni Gaudí took organicism to a structural level. He did not just copy nature’s appearance; he copied its engineering. His magnum opus, the Sagrada Família, is a testament to this.

- Structural Innovation: Gaudí used catenary arches (forms created by hanging chains), which allow for soaring heights without the need for Gothic buttresses.

- Natural Forms: The columns of the nave are designed to resemble giant trees, branching out at the top to support the vault.27

- Devotion: Gaudí was deeply pious, referring to nature as “The Great Book of God.” He lived as a pauper on the construction site in his later years. When he was struck by a tram and died in 1926, he was initially mistaken for a beggar.28

- History of Tragedy: The basilica has faced numerous setbacks, including the destruction of Gaudí’s models and crypt by anarchists during the Spanish Civil War in 1936. Yet, construction continues, funded entirely by private donations, with completion aimed for the centenary of Gaudí’s death in 2026.28

The Glasgow School of Art

Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s masterpiece, the Glasgow School of Art, demonstrates the starker side of the movement. While the library interior features dark wood and curving balustrades, the exterior is severe and functional. Mackintosh played with light and volume, creating a space that was disciplined yet deeply atmospheric, proving that Art Nouveau could be rigorous as well as decorative.21

The Object as Art: Decorative Arts

The Art Nouveau philosophy—that a vase or a chair is as culturally significant as a painting—led to a golden age of decorative arts.

Glass: Painting with Light

Glass was the perfect medium for Art Nouveau: fluid, translucent, and capable of capturing light.

- Émile Gallé (Nancy): A botanist and chemist, Gallé revolutionised glass art with his “cameo glass” technique. He layered different colours of glass and then etched away the top layers with acid to reveal landscapes and flowers in relief. His vases were often inscribed with poetry, serving as “speaking objects”.10

- Louis Comfort Tiffany (New York): Tiffany sought to recreate the iridescence of ancient Roman glass that had been buried in the earth. He patented Favrile glass (from “fabrile,” meaning handmade), where colour was ingrained in the molten glass itself rather than painted on. His lamps, with their bronze bases and leaded glass shades depicting wisteria and dragonflies, became icons of American luxury.10

Jewellery: The Value of Design

Before René Lalique, high jewellery was primarily a vehicle for displaying wealth—the value lay in the size of the diamonds. Lalique inverted this. He used “humble” materials like horn, ivory, enamel, and semi-precious stones (moonstones, opals) to create miniature sculptures.31 His “Dragonfly Woman” corsage ornament is a terrifying masterpiece: a gold and enamel hybrid of a griffin and a dragonfly, clutching a stone. Lalique proved that the value of a jewel lay in the artist’s imagination, not the carat weight of the gems.33

Furniture: The School of Nancy

Led by Louis Majorelle, the furniture designers of the École de Nancy treated wood as a plastic material. They used marquetry (inlaid wood) to create pictorial scenes of local flora (orchids, water lilies) on table tops. Legs and supports were carved to resemble roots or vines, giving the heavy wooden pieces a sense of organic buoyancy.17

The Invisible Hands: Women in Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau is famous for its depictions of women, but the role of women as creators has often been obscured by history. Recent scholarship has begun to correct this imbalance.

Clara Driscoll and the Tiffany Girls

For over a century, the design of the famous Tiffany lamps—the Wisteria, the Dragonfly, the Poppy—was attributed solely to Louis Comfort Tiffany. However, the discovery of a cache of letters in 2005 revealed the truth: these icons were largely designed by Clara Driscoll.35 Driscoll was the head of the Women’s Glass Cutting Department (the “Tiffany Girls”). She managed a team of women who selected and cut the thousands of pieces of glass for the shades. It was Driscoll’s artistic vision, combined with her technical expertise, that produced the studio’s most commercially successful and artistically acclaimed works.36 This revelation highlights a significant insight: while the movement often objectified women as passive muses, it also provided rare, albeit often uncredited, professional opportunities for female artisans.

Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh

In Scotland, Charles Rennie Mackintosh himself admitted, “I have talent, but Margaret has genius.” His wife, Margaret Macdonald, was a formidable artist in her own right. Her gesso panels and embroidery were integral to the “Glasgow Style” interiors. The couple worked collaboratively, blurring the lines of authorship in a way that modern art history is only now fully appreciating.1

The Socio-Economic Paradox: The Democratisation of Luxury

Art Nouveau was built on a contradiction that ultimately contributed to its downfall. Philosophically, many of its proponents (like Van de Velde and Horta) were socialists or social reformers. They believed that the working class deserved to live in beautiful environments, and that good design could improve social well-being.2

However, the very aesthetic of Art Nouveau—complex, asymmetrical, organic forms—resisted mass production. A Majorelle cabinet or a Tiffany lamp required hundreds of hours of skilled hand labour. They could not be stamped out by a machine.

- The Cost: Consequently, these “democratic” objects became the exclusive domain of the super-rich. Art Nouveau became the style of the elite, the very opposite of its stated intentions.

- The Paradox: Academic research on “luxury democratisation” suggests that while the desire for luxury was democratised during this period (through posters and magazines), the access remained restricted.4

The movement failed to solve the problem of affordable beauty. It would take the Modernists of the 1920s (Bauhaus), who embraced the machine aesthetic and simple geometry, to finally bring well-designed objects to the masses.

The Great War and the End of an Era

By 1910, Art Nouveau was already fading. The public was growing tired of the “excessive” decoration. The style was increasingly viewed as decadent, overly feminine, and impractical.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 was the final nail in the coffin. The war shattered the optimistic, romantic worldview of the Belle Époque. In the face of mechanised slaughter, the delicate, floral aesthetic of Art Nouveau seemed grotesquely out of touch.

- Shift to Art Deco: Post-war society demanded a new language: one of strength, speed, and machine precision. Art Deco emerged in the 1920s as the successor. Where Art Nouveau was curvy, biological, and nostalgic, Art Deco was angular, geometric, and celebrated the machine age.39

- Comparison: If Art Nouveau is a vine, Art Deco is a piston. If Art Nouveau is a dragonfly, Art Deco is a chrome bumper.

Resurrection and Legacy: From Psychedelia to Biophilia

Art Nouveau did not die; it went dormant. Interestingly, it has resurfaced in moments of cultural upheaval when society seeks to reconnect with nature or expanded consciousness.

The 1960s Psychedelic Revival

In the mid-1960s, the counter-culture movement in San Francisco rediscovered Art Nouveau. Concert poster artists like Wes Wilson and Bill Graham, creating art for bands like The Grateful Dead, looked to the Vienna Secession and Mucha for inspiration.40

- The Insight: The “melting,” illegible typography and swirling lines of the 1890s, which originally represented biological growth, were repurposed to represent the fluidity of the psychedelic experience (LSD trips). The rejection of the rigid grid in the 60s mirrored the rejection of Victorian rigidity in the 90s.41

Digital Design and “Contemporary Nouveau”

In the 21st century, we see a resurgence of Art Nouveau aesthetics in digital design. Dubbed “Contemporary Nouveau,” this trend blends the ornate typography and organic framing of the past with the clean vectors of modern software. It represents a longing for “craft” and “human touch” in an increasingly sterile digital landscape.43

Biophilic Design: The New Organicism

Perhaps the most profound legacy is in Biophilic Architecture. Modern architects and planners are validating the Art Nouveau intuition: that humans are happier when surrounded by organic forms.

- Mechanism: Studies show that “fractal” patterns (like those found in Horta’s ironwork or Gaudí’s columns) reduce stress and improve cognitive function.45

- Application: Today’s “green buildings”—skyscrapers covered in vertical gardens, offices with fluid, non-linear layouts—are the spiritual successors to Art Nouveau. They aim to solve the same problem Horta faced in 1893: how to make a dense, industrial city livable for the human animal.13

Conclusion

Art Nouveau was a shooting star in the history of art—burning with intense brilliance for barely two decades before vanishing into the smoke of the Great War. Yet, its brevity belies its significance. It was the bridge between the 19th and 20th centuries, the moment when the art world collectively decided to stop looking backward and start looking forward.

It was a movement of profound ambition and profound contradiction. It sought to be universal but became exclusive; it sought to be modern but looked to the primeval past of nature. While it failed in its economic mission to bring art to the masses, it succeeded in its aesthetic mission: to prove that the line of beauty is the line of life. From the uncompleted spires of the Sagrada Família to the green walls of modern eco-architecture, the “New Art” remains, in a very real sense, forever new.

Disclaimer

This report is intended for educational and informational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the historical and technical data presented, art history is a field subject to ongoing scholarly interpretation and revision. Attributions of specific works (e.g., the specific contributions of workshop assistants vs. masters) can be debated. Financial or investment decisions regarding art, antiques, or collectibles should not be based solely on this general overview, as the market for Art Nouveau objects is complex and subject to fluctuation.

Reference

- Art Nouveau – an international style – London – V&A, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/art-nouveau-an-international-style

- What is Art Nouveau? – Rise Art, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.riseart.com/guide/2417/what-is-art-nouveau

- Art Nouveau: A Harmony of Art and Nature – EMP Art, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.emp-art.com/emp-blog/art-nouveau-a-harmony-of-art-and-nature

- Is luxury expensive? – Research@emlyon business school, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://research.em-lyon.com/esploro/outputs/journalArticle/Is-luxury-expensive/9918089909453

- 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design – Terrapin Bright Green, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/reports/14-patterns/

- Art Nouveau – Wikipedia, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_Nouveau

- 9 Artists Who Defined Art Nouveau – TheCollector, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.thecollector.com/artist-defined-art-nouveau/

- The difference between Art Nouveau and Art Deco explained – Gallerease, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.gallerease.com/en/magazine/articles/the-difference-between-art-nouveau-and-art-deco-explained__6ae04a6d3cbf

- Art Nouveau | History, Characteristics, Artists, & Facts | Britannica, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.britannica.com/art/Art-Nouveau

- 7 Most Famous Art Nouveau Artists – M.S. Rau Antiques, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://rauantiques.com/blogs/canvases-carats-and-curiosities/7-famous-art-nouveau-artists

- What was the Art Nouveau movement? – Mayfair Gallery, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.mayfairgallery.com/blog/art-nouveau-style-guide/

- Different Names For Art Nouveau Movement – Art Deco Webstore, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.artdecowebstore.com/364/blog/221/different-names-for-art-nouveau-movement/

- The Influence of Art Nouveau on Modern Interior Design – Turpincrawford.com, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://turpincrawford.com/the-influence-of-art-nouveau-on-modern-interior-design/

- How Alphonse Mucha’s Iconic Posters Came to Define Art Nouveau | Artsy, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-alphonse-muchas-iconic-posters-define-art-nouveau

- The 40 different names of Art Nouveau, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://artnouveau.club/about-the-names-of-art-nouveau/

- The Art Nouveau Movement And Its Influence on Architecture – PAACADEMY.com, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://paacademy.com/blog/the-art-nouveau-movement-architecture

- École de Nancy – Wikipedia, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89cole_de_Nancy

- Art Nouveau | Aesthetics Wiki – Fandom, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://aesthetics.fandom.com/wiki/Art_Nouveau

- Art Nouveau – the Viennese version is called Secession – Time Travel Vienna, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.timetravel-vienna.at/en/art-nouveau-the-viennese-variant-is-called-secession/

- The Viennese Secession or Total Art – Galerie KLE, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://galeriekle.com/en/blogs/infos/la-secession-viennoise-ou-art-total

- Designing the New: Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Glasgow Style, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.museumaacm.org/exhibitions/designing-the-new.html

- Art Nouveau | National Galleries of Scotland, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/glossary-terms/art-nouveau

- The Sagrada Família: The Astonishing Story of Gaudí’s Unfinished Masterpiece, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.washingtonindependentreviewofbooks.com/bookreview/the-sagrada-familia-the-astonishing-story-of-gaudis-unfinished-masterpiece

- Sarah Bernhardt as Gismonda – Wichita Art Museum, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://wam.org/our-collection/collection/sarah-bernhardt-as-gismonda/

- Alfons Mucha, Gismonda | Highlights from the National Gallery Prague / Czech Center – New York, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://new-york.czechcentres.cz/en/blog/2021/07/alfons-mucha-gismonda-or-krizem-krazem-ngp

- Poster for ‘Gismonda’ – Browse Works – Gallery – Mucha Foundation, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.muchafoundation.org/en/gallery/browse-works/object/21

- The Historical Story Behind Sagrada Família’s Unfinished Construction, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://ticketsagradafamilia.com/the-historical-story-behind-sagrada-familias-unfinished-construction/

- Why Antoni Gaudí’s Sagrada Família Still Isn’t Finished after 136 Years | Artsy, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-tortured-136-year-history-building-gaudis-sagrada-familia

- The astonishing, sometimes tragic story of Antoni Gaudí’s fantastic obsession, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.catholicworldreport.com/2017/08/16/the-astonishing-sometimes-tragic-story-of-antoni-gaudis-fantastic-obsession/

- Ecole de Nancy (Nancy School), accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.nancy-tourisme.fr/en/discover-nancy/the-french-capital-of-art-nouveau/ecole-de-nancy-nancy-school/

- René Lalique: Master Jeweler of the Art Nouveau Movement – DSF Antique Jewelry, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://dsfantiquejewelry.com/blogs/journal/rene-lalique-master-jeweler-of-the-art-nouveau-movement

- Master Artist and Jeweler Rene Lalique – DigitalCommons@EMU, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://commons.emich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1114&context=honors

- Lalique – Antique Jewelry University, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.langantiques.com/university/lalique/

- The École de Nancy and the Spirit of French Art Nouveau – Proantic, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.proantic.com/antiques-art-design-magazine/the-ecole-de-nancy-and-the-spirit-of-french-art-nouveau/

- Clara Driscoll, the Tiffany Girls, and the Fancy Goods Department, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.museumaacm.org/newsletters/newsletter01162024.html

- Clara Driscoll and the Tiffany Girls: Shining a light on the designer and creators of Tiffany stained-glass lamps – The American Ceramic Society, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://ceramics.org/ceramic-tech-today/clara-driscoll-and-the-tiffany-girls/

- A New Light on Tiffany: Clara Driscoll and the Tiffany Girls – Flagler Museum, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.flaglermuseum.us/a-new-light-on-tiffany

- Culture Vs Luxury / The Paradoxes of Democratization, accessed on January 26, 2026, http://neumann.hec.ca/iccpr/PDF_Texts/EvrardY_RouxE.pdf

- Art Deco vs Art Nouveau | Rise Art, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.riseart.com/guide/2379/art-deco-vs-art-nouveau

- The Flowing Line: Psychedelia & the Art Nouveau Revival – SUU, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.suu.edu/suma/exhibits/2026/psychedelia-art-nouveau.html

- How Art Nouveau Inspired the Psychedelic Designs of the 1960s | Open Culture, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.openculture.com/2019/11/how-art-nouveau-inspired-the-psychedelic-designs-of-the-1960s.html

- “Art Nouveau on Acid”: Revisiting Sixties Psychedelic Concert Posters – Norman Rea Gallery, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.normanrea.com/blog/art-nouveau-on-acid-revisiting-sixties-psychedelic-concert-posters

- Art Nouveau in Graphic Design (Contemporary Nouveau Guide) – Zeka Design, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.zekagraphic.com/contemporary-nouveau-and-the-influence-of-art-nouveau-in-graphic-design/

- The resurgence of Art Nouveau – Muse Marketing Group, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://musemarketinggroup.ca/resurgence-of-art-nouveau-typography/

- Why Biophilic Design Is Crucial in the Workplace and Beyond – Gensler, accessed on January 26, 2026, https://www.gensler.com/blog/why-biophilic-design-is-crucial-in-workplace